Part Two: Brittle with Relics – A History of Wales 1962-1997

Today, Nation.Cymru is honoured to publish the second of two exclusive extracts from the newly published Brittle with Relics by Richard King. The first part can be read here.

The book is a landmark history of the people of Wales during a period of great national change, collecting the oral histories of Cymru and Cymraeg, of the people, place, and of ‘seismic events’ which have shaped Wales through recent history.

Introducing the collection of voices, Richard King reflects on his own place in the social, temporal, and physical landscape, and examines the tensions and arguments within Wales over what constitutes Welsh identity.

“There is no present in Wales,

And no future;

There is only the past,

Brittle with relics.”

— ‘A Welsh Landscape’, R. S. Thomas

Richard King

During the hour or so I spend at the Hen Fethel cemetery each year there is a steady stream of people, all going about the same business of cutting back grass and ivy, emptying flower-holders of their remnants and replacing them with new blooms.

The procession of visitors to and from the tap in the corner of the churchyard is distinguished by the stoic looks on their faces, as the winds suddenly swell around this lower mountainside and ice-cold water flows over their hands from the newly watered vases and containers.

It is rare not to be engaged by strangers in warm, if occasionally vague, conversations regarding ancestry, local connections, and historical neighbourly relations.

Nearly all of the activity at Hen Fethel is conducted in Cymraeg. The same was true of the conversations my grandparents had with their friends and neighbours while participating in events held at Hall y Cwm and of the funeral of my grandmother. This was the first occasion when I visited Hen Fethel.

My mother was one of only a scant handful of women present at the graveside as Chapel tradition meant that men alone normally attended the burial. It was a ceremony without any order of service or sense of formal structure, beginning at the house of my great aunt.

My grandmother’s coffin was placed in the dining room as the parlour filled with mourners and a crowd spilled from the doorway down into the street. A minister from the Nonconformist tradition proclaimed and declaimed for twenty minutes in a rich and vivid Cymraeg.

The majority of what he said was lost to my very basic Welsh. The language was one I was never taught, as it was considered irrelevant in the South Wales of my childhood.

Newport, Gwent, the town in which I was born and brought up, was one in which a certain section of the population seemed incapable of accepting it was located in Wales. Other than in my home, the only Cymraeg I heard spoken in Newport was by a neighbour, who commuted for an hour every day to attend the nearest Welsh-speaking school twenty miles away.

During the final four decades of the twentieth century Wales witnessed the simultaneous effects of deindustrialisation and a struggle for its language and identity.

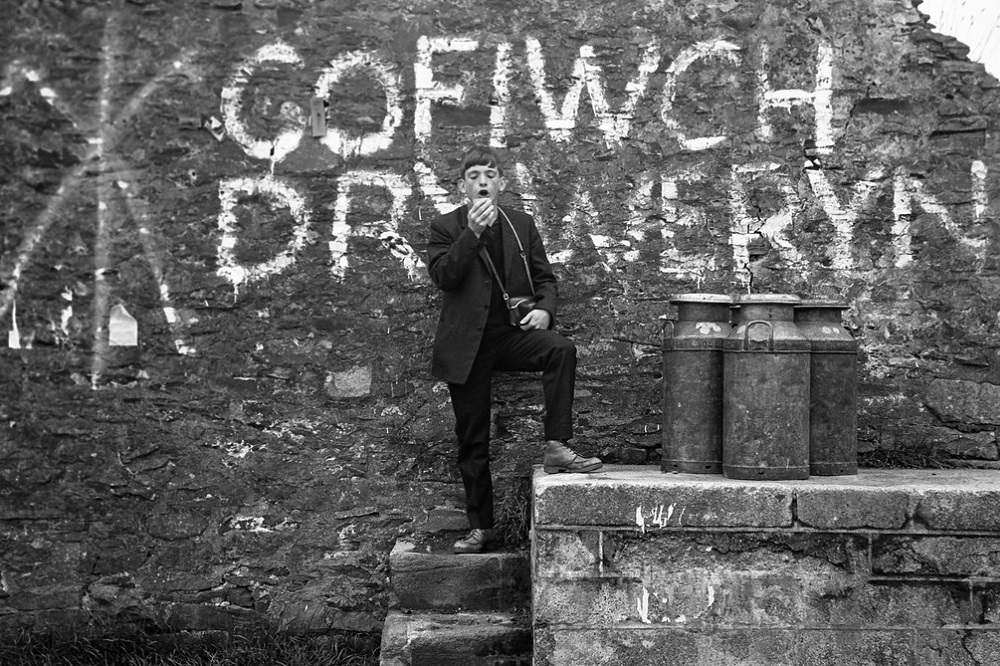

The country’s voice fought to be heard outside its frequently tempestuous borders and was argued over within them, as the people of Wales underwent some of the nation’s most traumatic and volatile episodes: the disaster at Aberfan; the inundation of Capel Celyn in the Tryweryn valley to create a reservoir for Liverpool; the rise of the Welsh-language movement and its policy of direct action; the Miners’ Strike and its aftermath; and the vote in favour of partial but significant devolution.

This history of Wales begins in 1962, with a radio speech delivered as a warning that Cymraeg, and the identity and way of life it represented, faced extinction. Titled ‘Tynged yr Iaith’ (‘The Fate of the Language’), the speech was given in the form of a radio broadcast by its author, Saunders Lewis, the former leader of Plaid Cymru.

The impact and influence of the speech have long been debated; what is certain is that Lewis’ polemic contributed to a renewed sense of purpose among those resistant to the language’s increasing marginalisation.

Over the subsequent three decades the case for Cymraeg would be campaigned and argued for with an applied fervour. In 1990 Welsh became a compulsory subject for all pupils in state schools in Wales up to the age of fourteen.

Three years later the Westminster government passed a Welsh Language Act, which formally recognised that ‘in the course of public business and the administration of justice, so far as is reasonably practicable, the Welsh and English languages are to be treated on the basis of equality’.

As the decline in the language was gradually halted, the industrial centre of South Wales – the area in which over half of the country’s population lived and worked and where the Welsh language was heard less frequently than English – entered into a moderate then accelerated decline of its own.

The heavy industries of steel, oil and mining were all significant employers in the region; the centre of the last of these was the South Wales Coalfield, home to the historic communitarian radicalism fathered by the Miners’ Federation and its welfare institutes and libraries.

The libraries, the Manic Street Preachers would sing, ‘gave us power’. In the year of Saunders Lewis’ radio lecture, a job in heavy industry offered above-average terms and wages in a form of employment that had strong links with the area in which the work was based. As well as payment in exchange for labour, the work provided social capital.

In these close-knit communities, employment was ingrained with identity, an attribute that grew in significance during the increasing secularisation of Wales that had gained momentum by the 1960s.

Wales consequently experienced a period lasting almost forty years in which two distinct energies animated the country. The first derived from an often youthful, determined movement dedicated to the survival and revival of Cymraeg; the second energy came out of a crisis, one not limited in this period to Wales nor any of its regions, but one the country, due to its reliance on heavy and light industry, experienced acutely: an initially gradual then substantial reduction in remunerative long-term employment opportunities.

The country’s political and legislative authority, such as it was, was held in the Labour stronghold of the South, a part of Wales that often considered itself to be as British as it was Welsh. Here, in the offices of MPs and powerful, usually male-dominated council chambers, concerns for the fate of the language and the ideas of Welsh independence proposed by Plaid Cymru in the west and north-west of the country were marginal issues.

Such concerns were at best dismissed as student politics. For much of this period, in the eyes of South Wales Labourism, a self-governing Wales was a cause proposed by dangerous nationalists, or ‘Nats’. The country was accordingly often forced to navigate its way through a period of great change in a state of internal contradiction and frequent animosity.

This history concludes with the vote for Welsh devolution in September 1997, held five months after the Labour Party had been returned to government in the UK for the first time in eighteen years.

The vote was carried by a majority of 6,721, or 50.3 per cent of the vote, among the narrowest of margins in British electoral history. The country nevertheless voted for the limited form of self-determination represented by the creation of a National Assembly for Wales.

Oral history

In order that the participants in this history are heard on their own terms and by their own authority, this book is an oral history, a form that favours the grain of the voice and the grain of the Welsh voice in particular. The voices in this book bear witness to the struggle Wales endured during the period and frequently belong to people determined to rectify the damage left in that struggle’s wake.

A great number of these voices will be familiar to the reader; others may not be. Many of those present are speaking in their second language. And there are voices missing from this history that belong to people now departed, or to people who, despite their willingness to share them, no longer trust in the accuracy or function of their memories.

The history of the relationship between Cymru and Cymraeg, between Wales and its language, has most usually been told in the mother tongue. To present the history of the Welsh language during the period covered in this book in English is an act of faith: it is one not entered into lightly.

This is a history of a nation determined to survive during crisis, while maintaining the enduring hope that Wales will one day thrive on its own terms.

Brittle with Relics is published by Faber and can be purchased here or from good bookshops

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.