Part two: Remembering the Tonypandy Riots

This week marks the anniversary of key events in the Cambrian Combine Dispute of 1910. Here’s the second of three special articles about the ‘Tonypandy Riots’ by John Geraint, author of ‘The Great Welsh Auntie Novel’, and one of Wales’s most experienced documentary-makers. ‘John On The Rhondda’ is based on his popular Rhondda Radio talks and podcasts. You can read part one here…..

John Geraint

Tonypandy, November 1910. After a night of disturbances at the Scotch Colliery, the Chief Constable of Glamorgan has sent for armed soldiers to restore order. Miners in a dispute with D. A. Thomas’s Cambrian Combine are trying to force the coal-owners back to the negotiating table by picketing the colliery’s Engine House or Power House.

What happens next has been a matter of fierce debate ever since – in the House of Commons, in the minds of historians and in the cafes and pubs of Tonypandy: did Home Secretary Winston Churchill send in the troops against unarmed British citizens who’d been locked out of their place of work?

In 2010, I directed and produced a BBC documentary, ‘Tonypandy Riots’. It marked the centenary of the Cambrian Combine Dispute.

We filmed schoolchildren gathering at the Mid-Rhondda Athletic Ground, where back in 1910, on the morning after those disturbances at the Scotch Colliery, thousands of miners came together for a mass meeting to decide on their next move.

A telegram is read out to them, a telegram from Churchill in London which seems to bear out what he and his family always claimed – that rather than sending in the troops, Churchill held them back:

“You may give the following message from me to the miners. Their best friends here are greatly distressed at the trouble which has broken out and will do their best to help them meet fair treatment… But rioting must cease at once so that the inquiry shall not be prejudiced and to prevent the credit of the Rhondda Valley being injured. Confiding in the good sense of the Cambrian Combine workmen, we are holding back the soldiers for the present and sending police instead. Winston Churchill.”

There was a precedent for sending armed troops to confront striking miners, a shameful one: the ‘Featherstone Massacre’. It ended with soldiers shooting Yorkshire miners dead.

Churchill seems desperate to avoid any repeat. And satisfied that armed forces aren’t going to be deployed against them, the Tonypandy miners leave the Mid-Rhondda Ground to march down to the Power House to resume their peaceful picket.

Cavalry

But that’s not how it turns out. The police refuse to let them speak to the blackleg workers who’re keeping the pumps operating, preventing the Scotch colliery from being flooded; preventing D. A. Thomas from suffering damage to one of his valuable assets.

At five o’clock, the stone throwing starts. The Power House windows that face the roadway are shattered. The Chief Constable gives the order for mounted police to charge to clear the road. The battle lasts for two hours.

Wooden palings are ripped down for weapons. There are baton charges. The police make good use of their truncheons. Hundreds of men are injured, many with head wounds.

Later, one miner, Samuel Rays, dies from skull injuries.

A panicked local magistrate sends again for troops: ‘Police cannot cope with rioters at Llwynypia… Troops… absolutely necessary for further protection.’

And this time, less than 24 hours after the promise he’s telegrammed to the miners, Churchill acquiesces in the request. He messages the military commander Major General Nevil Macready:

“As the situation appears to have become more serious you should, if the Chief Constable or Local Authority desire it, move all the cavalry into the district without delay.”

A Rising

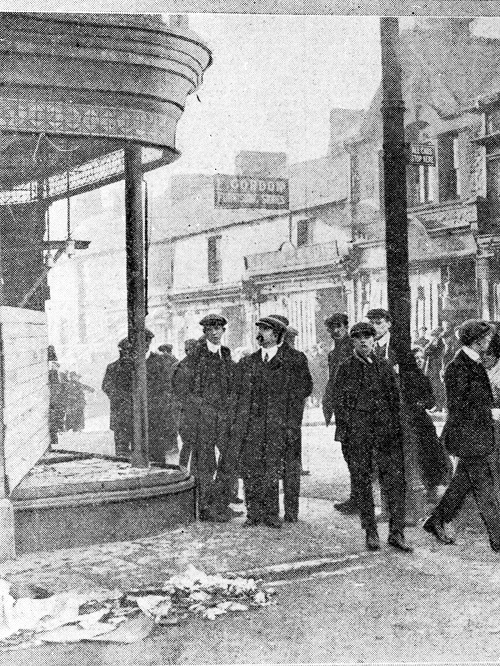

Pushed back now to Tonypandy Square, the battered miners regroup.

In front of them, the mayhem at the Power House. Behind them, Dunraven Street, the retail paradise that’s been built for them. That’s where they turn.

Windows are smashed, shops ransacked, goods stolen. The damage is estimated in the tens of thousands of pounds – probably millions at today’s values. It’s dubbed ‘Tonypandemonium’.

But this isn’t a mob without a mind.

As historian Professor Dai Smith has said, “The crowd is not organised, but it knows what to do.”

One of the few shops left undamaged was the chemist’s owned by local rugby hero Willie Llewellyn: his exploits in helping Wales beat the All Blacks aren’t forgotten even in the heat of Riot.

Riot? You could call it that, certainly.

But looked at another way, it’s a Rising, a brief but deliberate act of defiance by downtrodden people: a Rising against their masters, the coal-owners who would deny them a living wage; a Rising against the class of shopkeepers, who – with exceptions – want to define the Rhondda their way, as a community they can profit from, preside over and control; a Rising against the State which – despite the assurances of the Home Secretary – seems willing to use all its might on one side of the argument.

The troops

At lunchtime the next day, the troops arrive – the 18th Hussars wearing khaki service dress and carrying carbine swords, the Lancashire Fusiliers who take their rifles and bayonets to their billets in Llwynypia.

Because they’re not here on a day trip. There will be troops in Tonypandy well into the next year.

But their commander General Macready is less willing to go along with the demands of the coal-owners and the panicking local magistrates than they may have anticipated.

His calm assessment of the stand-off at the Power House confirms what historians say – that the miners were never trying to occupy the colliery, they were responding to what they saw as the owners and police colluding to make a symbolic stand against them:

“Investigations on the spot convinced me that the original reports regarding the attacks on the mines on November 8th had been exaggerated. What were described as ‘desperate attempts’ to sack the power-house at Llwynypia proved to have been an attempt to force the gateway, against which an ample force of police under the Chief Constable was available on the spot… had the mob been as numerous or so determined as the reports implied, there was nothing to have prevented them from overrunning the whole premises.

That they did not was due less to the action of the police than to the want of leading or inclination to proceed to extremities on the part of the strikers.”

‘Gentle persuasion’

All the same, Macready’s troops are effectively an army of occupation. They ensure that mass demonstrations against blackleg labour will be ineffective. They nullify the picketing which the leaders of the strike had seen as their only hope of victory. And they do come into direct contact with the strikers.

Bayonets are used for what’s described as ‘a little gentle persuasion’.

The miners and their families can do little but eke out their meagre strike pay and stand firm together.

The troops are out in massive force in December, when thirteen miners are summoned to Pontypridd Magistrates Court to stand trial.

Bugle calls echo through mid-Rhondda once again. Accompanied by Drum and Fife Bands, 10,000 people answer the call, marching down to Ponty to support those who the authorities are determined to make an example of.

It’s a remarkable demonstration of solidarity. At the head of the mile-long procession, a banner proclaims the defiance of the miners – ‘Hungry as L’ it seems to say, the L written as a big capital letter. But viewed closer up, it actually reads ‘Hungry as Lions’.

Food is an issue, though. As winter draws on, the children of Tonypandy are being fed in soup kitchens.

A London newspaper reporter writes that the brooding, sullen atmosphere up and down the streets of the Rhondda is like something he’s experienced in Russia in those years that led up to the overthrow of the Tsar.

There’s revolution in the air.

The next installment will be published tomorrow.

‘John On The Rhondda’ is broadcast at about 3.15pm as part of David Arthur’s Wednesday Afternoon Show on Rhondda Radio

All episodes of the ‘John On The Rhondda’ podcast are available here

John Geraint’s debut in fiction, ‘The Great Welsh Auntie Novel’, is available from all good bookshops, or directly from Cambria Books

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

The same Nevil MacCready that was appointed by Lloyd George to command the British army in Ireland in 1921 and stated that he hated the Irish more than the Germans! Not an endearing personality to the Celts!