Part two: The Great Welsh Auntie Novel by John Geraint

Election Night, February 1974. On a bus stop on Tonypandy Square, 17-year-old Jac has been waiting for two Sixth Form friends, Petra and Lydia, and hoping – without much hope – that a third girl, Catherine, will be with them.

Prompted by a kind of vision of the Tonypandy Riots of 1910, and the miners’ leader of years gone by, Jac has made a solemn vow – to grow up; and to ask Catherine out.

Nation.Cymru is delighted to publish the second part of documentary maker-turned-novelist John Geraint’s seriously playful “Great Welsh Auntie Novel” along with a reading by the author.

John Geraint

“Petra!” cried Jac, “A rose-red beauty…”

It was just Petra and Lydia. No Catherine.

As the two girls strode up to within proper talking distance, Lydia pulled a face.

“Not again, Jac! Not that old chestnut again. Stop right there. Please.”

Petra went ahead anyway, mimicking perfectly, from somewhere deep down in her boots, Jac delivering his well-worn parody of one of nineteenth-century literature’s most quoted lines: “A rose-red beauty, half as old as I’m.”

The Prince of Repetition laughed. At the accuracy of Petra’s take-off of him, yes. But mainly at his own joke. His word-play would bear repeating many times yet.

Lydia took a different view: “You mangle that poem every time Petra wears her scarlet coat, and I still can’t work out why you think she’s half your age. It’s pretty obvious which one of you is less mature.”

In their hurry to make the bus, Lydia’s glasses had steamed up. She swiped the brown frames off her face with a wave of her hand and polished the thick lenses in her scarf.

Honey-haired Lydia Peake. No nonsense from her.

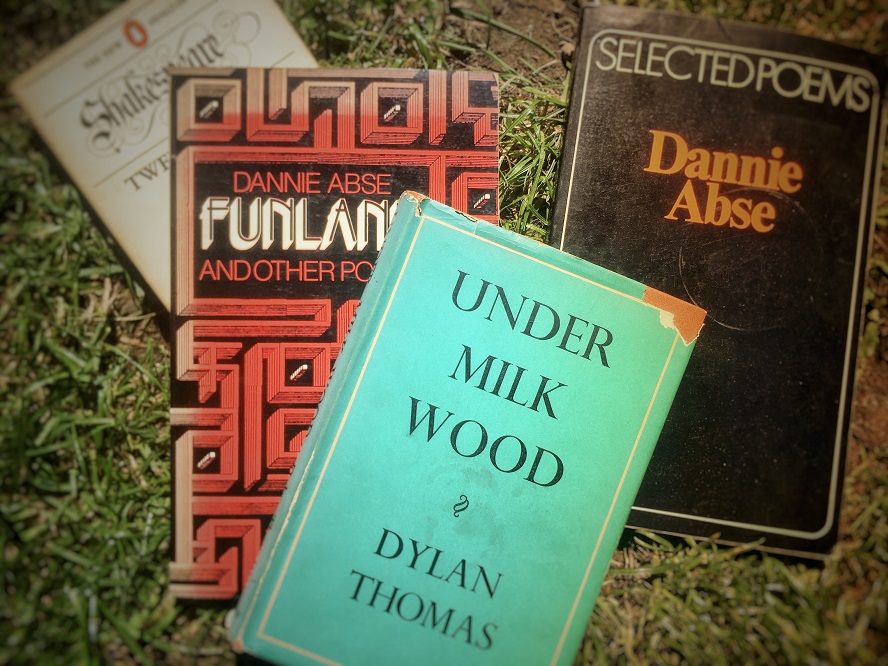

Jac might have read some poetry; she’d read a lot. Her latest enthusiasm was for Wales’ own Dannie Abse, newly raised to the canon of the Sixth Form syllabus: so reasonable, so precise.

Of course, she had to rate him, given the odd coincidence of her name being a near-homophone of Lydia Pike, the fictional object of Abse’s teenage obsessions.

She’d even lent Jac a book by Abse, a coming-of-age novel. Autobiographical. Ash On A Young Man’s Sleeve.

“Thank you, Miss Peake,” Jac said. “Good evening and welcome to you, too.”

Lydia Peake. Lydia Pike. It was an odd coincidence. How many A level candidates get to study a literary character of practically the same name? But this was the Rhondda.

Charged synchronicity

And there, over Lydia’s left shoulder, Jac could still see James Taylor, in his Welsh guise, so reminiscent of the American one.

Strange conjunctions abounding: a charged synchronicity swirled around Pandy Square tonight. Well, it was the core of it all. The Node. The Epicentre.

A charged synchronicity? I like it, thought Jac. I must try it out on Martyn.

You’d better crack that Tonypandy Torquemada line first.

Synchronicity didn’t seem to operate in favour of ‘Petra’. The name was a rarity locally. In a way, she’d got off lightly.

Her parents had decided to call her Cora Petula, which would have been insanely exotic for the Rhondda; but her father had stopped for a pint on his way to register the birth.

He ended up not only getting the names in the wrong order but also squashing them together. Pet-ra. Petra from Pentre.

Mind you, merged the other way round, she’d have been ‘Coula’, like a fridge compartment. What fun Jac would have had with that!

All the same, it was a burden, being the namesake of a television dog. How many times had The Prince Of Repetition teased her about what she was up to on Blue Peter that week? Or wondered aloud whether ancient Jordan had boasted an enchantress called ‘Pentre from Petra’?

Solemn vow

A rose-red beauty…

This Rhondda Petra was a beauty. Dark-haired and dark-eyed, tall, slim.

Not Jac’s beauty, but Martyn’s. They’d been seeing each other ever since they’d taken leading roles in the dramatised reading of Under Milk Wood which had been put on in the autumn to mark the Boys’ and Girls’ Grammars merging, in preparation for going Comprehensive.

Martyn and Petra. A match made in Llareggub. First Voice and Rosie Probert. Like Burton and Taylor in the film version. A passion fuelled by allure and alcohol. Stars of the show. And about to shine again, next term, in a fully staged Shakespearean comedy.

Jac considered again the telling off he’d got from Lydia.

So much for the solemn vow he’d just made. He couldn’t rein in the punning for five minutes. Lydia was right, it was a form of showing off, of trying to prove how well-read he was, how cultured, almost like Martyn.

Though Martyn was never childish, even at his most petulant…

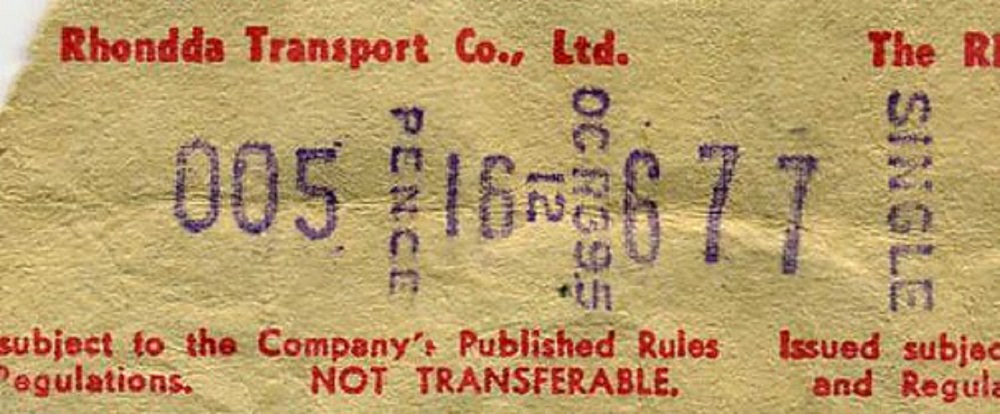

Suddenly, the Blaencwm bus was at the stop. How had Jac managed to screen out the approach of a bright red twelve-ton double-decker?

His mind’s on other things, as his Auntie would say, whilst he sat in the corner reading, family life going on all around him.

Sacred ground

They boarded, settled themselves on the maroon double-seats upstairs.

A film of condensation fogged the windows. Jac reached across with his forefinger to spell out something witty on it.

Then he remembered his vow, and used his whole hand to wipe an arc of the glass clear instead, just in time to glimpse the furniture shop on the corner opposite as the bus pulled away. ‘Mr Burton’s Wardrobe by Times Furnishings, Pandy Square’.

He must use that some time. Or some variation on it. Or maybe not. Grow up!

Then on, past The Record Shop, past Jerusalem. O Jerusalem, Jerusalem….

How many places of worship did one town need?

Here was another, Zion. The Methodists.

The bus jerked, then picked up speed, as Llwynypia Road straightened into the distance.

This was sacred ground. Not the Promised Land prophesied in those chapels, but the roadway where thousands of miners had pushed forward on that November night in 1910, challenging the cordon of Metropolitan Police, newly arrived to guard the gates of the Scotch Colliery.

Jac could feel himself moving with them, moving with the tide of history, ready and willing to break himself on the mole of that police line, to sink under the blows of their batons. To sink, only to rise again.

Something… sinister?

Something had moved then, something had shifted.

That was true now too.

Not just politically, but personally. Amongst his friends.

Looking at Petra, Jac knew it. Something in her relationship with Martyn had… metastasised, was that too strong? Mutated? Something that had always been there had stirred. Is about to come spewing out.

No, not tonight, not again… but, yes, maybe that too. There was only so much vodka that even Martyn could swallow. Though he didn’t seem to know it when he got in one of his moods. His depressions.

Jac always tried to attune himself early to shifts of emotion amongst his friends.

The only one of them who never took a drink, he was continually on the look-out for trouble, seeking to head it off, to play the peacemaker or the comforter.

That was how he saw himself, at any rate. He understood, or at least he thought he did, that the way Martyn drank was different.

Other friends would begin in good heart, downing two or three drinks. Only then, when they took that one too many, would they get maudlin. Or sick. Or both. It could happen quickly, but it always seemed unintentional, accidental rather than purposeful.

The downstroke

With Martyn, the downstroke was there from the beginning, designed into the process. He just kept sinking, lower and lower.

It could be frightening.

But in the last few days, something else had altered, something deeper again.

Jac felt it, caught it, in the smallest of Martyn’s responses, in the way he’d talked about plans for the party that night. Or not even that, just a look in his eyes. An avoidance of some reckoning to come.

Petra must sense it too, would have been the first to sense it, even if she couldn’t fathom what it was. Something… sinister? Yet completely part of who he was, this man-boy she’d let herself fall in love with and wanted to love better.

D’you reckon that’s how girls think? Really?

Jac had no way of knowing, no experience of true love, no romance of any description in his past, beyond a few short dates at the Picturedrome and the Plaza.

One short date at the Picturedrome, in point of fact.

Despite that, he allowed his conjectures to race onwards. Petra wanted to make Martyn right, to make him whole. To plumb his darknesses, to feel that from the bottom of her own heart she could speak to him and his needs and, yes, even his depressions.

But always feeling adrift, out of her depth. Needing something, someone to anchor her, to anchor them.

Society of friends

Maybe that something was the crew, the gang, The Society of Friends.

It was Petra herself who’d christened them that, one home-time after Jac had picked out those words from the sign outside Maes-yr-Haf, as the school-bus passed the Quaker settlement on Brithweunydd Road.

Reading aloud signs and notices that everybody could plainly see for themselves – that was another habit Jac was trying to teach himself to curb.

But this time it had had a happy outcome: their clique was well named.

The Society of Friends.

There was something of a sect about them, the cast who’d come together for Under Milk Wood. For Jac, they represented an escape from the narrowness of his Chapel upbringing. But there was something spiritual in their commitment to each other all the same, something pure and demanding.

Already, they’d spent so much precious time together, they were so much part of each other’s hopes and dreams, so bound up in each other, that Jac knew that nothing could come between them.

Petra and Martyn. Lydia, Penry, Nerys. Jac. And Catherine.

All of them so different.

But with so much in common.

So intimate that it could hurt.

The Great Welsh Auntie Novel by John Geraint is published by Cambria Books, from next week and you can buy a copy here or in good bookshops.

Part one can be read here. We’ll have another exclusive extract next week.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.