Penblwydd hapus yn 80 oed John Cale – Wales’ most influential musician

Leon Barton

Leon Barton

Heol Cwmamman in Garnant, Carmarthenshire (population 2,023 at the last census) is one of those classically Welsh sloping streets. It’s now home to a shop, a pub, a pharmacy, a chinese takeaway and several houses; there’s nothing particularly remarkable about it. But 80 years ago, on March 9th 1942, it was the road on which one of Wales’ most remarkable cultural figures – and surely the nation’s most influential musician – was born.

There’s a theory – put forward by my friend Russell Todd – that every Welsh music fan can remember where they were when they found out one of members of The Velvet Underground was from Wales. Manic Street Preachers frontman James Dean Bradfield certainly can: ‘I had this moment when I was 15, listening to (second Velvets album) White Light/White Heat… there’s a song called ‘The Gift’, and John Cale narrates it. It’s about a man who mails himself to his girlfriend as a present. She opens it, and she fucking kills him. I remember listening to that song and I was like, “Fuck me! That sounds like a Welsh voice!”. My mind exploded: one of the pivotal members of The Velvet Underground was a Taff! Anything’s possible!’

Anything indeed. Despite leaving at the age of 18, perhaps no other major artist or performer – not even Richard Burton or Dylan Thomas – has ‘carried’ Wales so intrinsically, and in doing so shown the wider world a glimpse of what Welshness is; mournful, mercurial, brooding, lyrical, fiery, industrious, romantic, black-humoured, volatile.

Plus, he’s a survivor. Thomas died drunk at the age of 39, Burton only made it to 58. Cale is about to enter his ninth decade. When the body of work as a whole is considered, it doesn’t even feel eccentric to me to describe him as Wales’ greatest ever artist.

Smalltown

An only child born to a 39 year old mother, he became, to a large degree, her project. ‘I spoke Welsh. I learned English at school at about the age of 7. I couldn’t talk to my father until then. My Grandmother ruled the roost… the whole idea of her is repulsive to me. She banned the use of English in the home and it made me feel very uncomfortable. I was treated as not worth the time and she treated my father like that as well. I didn’t understand the volatility and hatred that came from her. I understand it now of course – here was my mother, a school teacher, her only daughter, who gave that up to look after me and who married an English-speaking, uneducated coal miner, which is exactly what she fought tooth and nail to keep her family away from’ he told the Guardian in 2011.

Cale has talked about how the (at best) awkwardness/(at worst) sheer madness of his homelife at least gave him the determination ‘to get out and do something’.

With his mother being an ex-teacher (and a renowned one too. She had pioneered a form of teaching at the local primary school that centred around inductive – as opposed to rote – learning) there was a lot of emphasis on education. She taught him piano from the age of 7 before turning him over to another teacher when the young John’s talent expanded beyond her expertise. ‘By the time I was ten I was doing about four exams a year… I would spend all my evenings practicing… I wanted to be outside playing soccer but music was kind of a shot at life’.

At the same time, ‘my mother told me she doesn’t care what I do as long as I don’t hurt anybody. I really admire what my mother put up with and handled – she protected me in a very good way…I learned from her about bringing things out of people and letting them lead you to where they want to go. I think that’s why I enjoy collaboration so much’.

Grammar school

After passing the 11 plus Cale headed to school in Ammanford. ‘Grammar school had a roster of instruments. At first when I went to join the school orchestra they had nothing but about a year later they found a viola – the saddest of all instruments. No matter how good you are, how fast you play, you can’t get away from the character – the melancholy – of it’.

His bedroom was where the hot water boiler was. But he also had a radiogram, given to him by his uncle Davey Davies, who, along with wife Mai Jones, ran the number one programme on BBC Radio Wales. ‘Welsh Rarebit’ was a talent show that could count Harry Secombe and Shirley Bassey among it’s discoveries, and Jones’ in particular had an effusive attitude that was to influence Cale; ‘she taught me how music could be a form of entertainment that made people feel good’.

In response to a series of asthmatic or bronchial attacks, he was prescribed Mr Brown’s, a notoriously strong cough syrup that was laced with opium. Watching the patterns on his bedroom wallpaper gently pulse and mutate with the sounds of early rock ‘n’roll, jazz and leftfield classical music coming from his radiogram via radio Luxembourg, Voice of America and the BBC’s Third programme, the connection between music and altered headspace was formed at a young age…

‘Libraries gave us power’ sang Bradfield’s band in ‘Design for Life’, The Manics’ dissection of ‘Welsh working class life, a line that clearly resonates when considering the Cale story.

‘I latched on to the local library… a little miners community library. And I found that I could go there and fill out a form and say I wanted a piece of music by (Austrian avant-garde composer) Ligeti and it’s brand new from Universal publishers… and they would get it for you! I learnt so much that way.. I got all the books I wanted about Karl Marx.. so much came from that library’.

In order to further sate his thirst for musical knowledge Cale took organ lessons at the local church. It was to lead to one of the darkest moments of his childhood when he was molested by the organist. ‘It certainly took care of my religious sensibility’ he wrote in his 1999 autobiography ‘What’s Welsh for Zen’.

Rebellious

‘Music and the Welsh Youth Orchestra made me want to get away from home and do something. I was pretty rebellious. There was a certain point when I got too smart for my boots and I didn’t want to put up with this any more, and it happened to be about the time that rock’n’roll surfaced. From there on it was fun and games. Music became a very enticing language for me because I could communicate with people without having to say anything in English or Welsh’.

One day at school, two formal looking Londoners from BBC Wales visited to find talented children to record for a radio show. Cale’s music teacher Mrs Roberts recommended him and they liked a self-written piece he showed then called ‘Toccata in the style of Khachaturian’. But when the Londoners came back to make a recording, they’d lost the score. The young Cale was forced to improvise, something he later described as ‘two and a half minutes that changed my life’. The sense of exhilaration was intoxicating. ‘From then on I knew what I wanted to do: I wanted to play music and improvise’.

Although Cale’s ears were open to all musical styles, the precision involved in being a classical musician was ‘a culture that I was utterly disturbed by… it didn’t encourage personal expression’. He knew he had to head to a place where his desire to undertake musical explorations would be stimulated.

As Lou Reed sang on ‘Songs for Drella’ the 1990 album he and Cale made following the death of Andy Warhol, ‘there’s only one good thing about a small town – you know that you want to get out’.

So age 18 it was off to Goldsmiths Teachers College in London, mainly because ‘from there I thought I would find out how to get to New York’. It was always America. ‘I veered towards New York very early on.. as soon as I started reading books about New York poets and writers… and then I ran into John Cage and I thought that was where the new avant garde was coming from… and when I talked to Cage about it he said yeah, it’s the place but I’m not the person any more. It’s La Monte Young’

When one of Cale’s musical heroes, the avant-garde composer John Cage visited London to search for talented musicians the 21 year old told him that whether he got a scholarship or not he was headed for America anyway. As it happened, he was awarded a place at the prestigious Tanglewood music institute in Boston.

European Son

At Tanglewood Cale took lessons from the lead viola player of the Boston Symphony Orchestral, and soaked up every musical opportunity that came his way. But it was going to New York and hooking up with La Monte Young and his Dream Academy that was to propel his musical ambitions forward. Young’s ensemble explored the use of drones, holding notes for hours at a time, and in doing so, attempt to glimpse the discordant beauty that would emerge from sustained sound.

‘I was a little bit lost and trying to find my way in a maze of different musical opportunities that were around…and chose the one that was most difficult in the avant-garde, which finally just burnt itself out. I realised I’d wanted to be in a rock ‘n’ roll band since I was 14, ever since I had a jazz band in Ammanford’.

Meanwhile, a 22 year old jobbing songwriter for tiny label Pickwick records, born a week before Cale, was feeling restless and looking for a new outlet for his musical ambitions. Lou Reed explains how he met the Welshman; ‘I wrote a song called The Ostrich, and they decided that they wanted to have a group say they did it.

Because it was just me and the other three guys who did it. And I’d taken a guitar and tuned all the strings to the same note. I did that because I saw this guy called Jerry Vance do that. Jerry Vance was not an advanced avant-garde guy, he was just screwing around. And he didn’t realise what he had. But I did. And I took that and made it into The Ostrich. Then they wanted to have a group to say that they recorded it, called The Primitives. So this guy went out to a party to find people with long hair and he brought in Cale. He brought in Cale, Tony Conrad and Walter De Maria; they were all artists. You got in fights in those days if you had long hair’.

The two were immediately taken with each other. ‘Music pours off John like water down a mountain’ said the New Yorker.

Cale encouraged him to play him some of his songs that were not meant for Pickwick, and wasn’t particularly enamoured at first. But then he took a closer look at the lyrics to ‘heroin’ (a graphic depiction of shooting up) and ‘waiting for the man’ (a description of buying illegal drugs) and realised his new friend had basically created a new language for writing lyrics. ‘Lou was a poet at heart and I realised that if I could improvise with the viola or any other instrument Lou could improvise with words. In really expert fashion’.

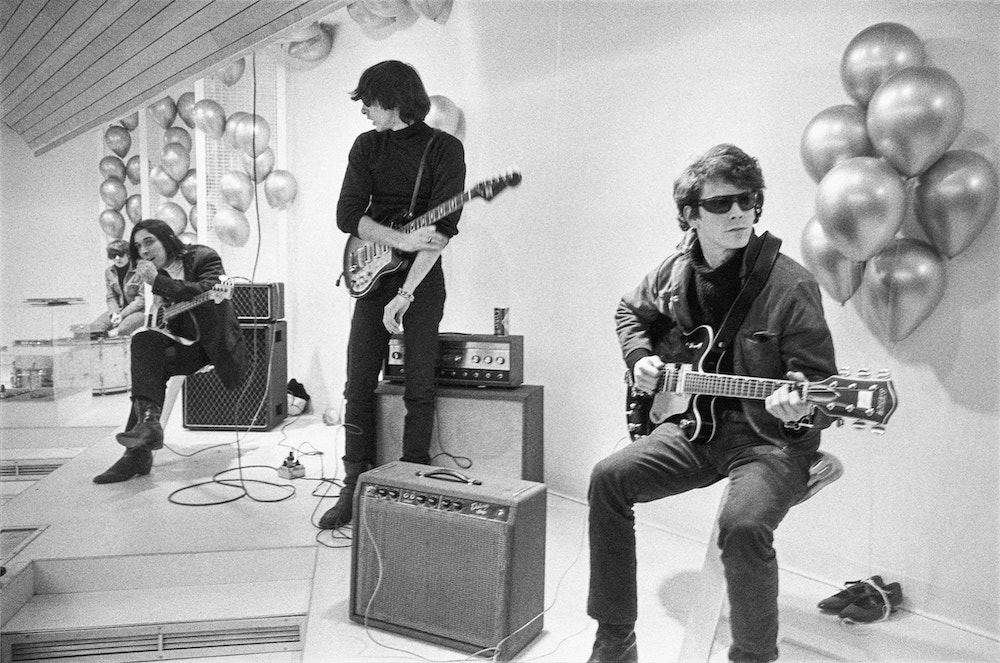

Reed’s friends Moe Tucker and Sterling Morrison then came on board on drums and guitar and The Velvet Underground (name taken from an underground novel by Michael Leigh) was formed. Although early audiences were usually left far from impressed, the band soon came to the attention of celebrated pop artist Andy Warhol, then at the height of his fame. He became their manager and his ex-fire station workspace ‘The Factory’ became The Velvets rehearsal room. The Factory was home to all manner of artists and beautiful people and the stunning German model Nico (born Christa Päffgen) was one of them. Warhol suggested she join the band, Reed promptly fell in love and their brief affair resulted in such memorable songs as ‘I’ll be your Mirror’ and ‘All tomorrows parties’.

For all of Cale’s classical training and avant garde leanings, his 2004 appearance on Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs saw him pick popular music contemporaries such as Bob Dylan (‘she belongs to me’ – 1965), The Beatles (‘he said she said’ -1966) and The Beach Boys (‘In my room’ – 1963). Upon hearing The Small Faces debut single ‘whatcha gonna do about it’ in 1965 his response was ‘we better get a move on… these guys are already using noise as a solo’, whilst the musical similarity between early Velvet’s track ‘There she goes again’ and Marvin Gaye’s ‘Hitch Hike’ (1962) have long been noted.

So it’s not as if the band’s sound came out of nowhere. It’s just that, particularly through Cale, The Velvet Underground wanted to take things further. And they did.

‘As soon as we’d done ‘Venus in furs’, I knew that we had something… something that would be really hard to define… but it had an amazing theory of arrangement behind it. The drone worked, it gave you a tapestry’. Even now, the dark, thrilling power of ‘Venus in Furs’ – with Cale’s viola hypnotically droning and screeching throughout – stops me dead. It’s so, so striking, that it still seems incredulous that their debut album was virtually ignored upon its 1967 release. Rolling Stone magazine didn’t even bother reviewing it, it peaked at 171 on the US Billboard chart and went on to only sell 30,000 copies in its first five years.

‘But’, as producer/musician Brian Eno famously said ‘I think everyone who did buy it started a band… some things generate their rewards in second-hand ways’.

Revelation

Among the few who loved it was a 19 year old singer/songwriter by the name of Davey Jones, who at that point had only a series of flop singles under his belt. It was to have a profound impact. ‘My manager brought back a record, a plastic demo of Velvet’s first album, which Andy Warhol had signed in the middle’ he recalled in an interview with PBS. ‘He said, ‘I don’t know why he’s doing music, this music is as bad as his painting’ and I thought, ‘I’m gonna like this!’ I’d never heard anything quite like it, it was a revelation. It influenced what I was trying to do’ he went on ‘(although) I don’t think I ever felt that I was in a position to become a Velvet’s clone. But there were elements of what I thought they were doing that were unavoidably right for both the times and where music was going. One of them was the use of cacophony as background noise.. to create an ambience that had been unknown in rock’. Jones would soon change his surname to Bowie and the rest is rock ‘n’ roll history.

It’s perhaps in Europe that the band’s artistic ambitions first found widespread appreciation amongst fellow musicians. ‘They played like pigs’ Can guitarist Michael Karoli told Melody Maker in 1975. ‘Never before was there such violence on record. We thought they were brilliant’.

Mojo magazine placed ‘The Velvet Underground and Nico’ at number 7 in its list of 100 records that changed the world, saying that without it there would be ‘no rock counterculture; no Bowie, Iggy, Alice Cooper, avant rock, Krautrock, punk, goth, Sonic Youth, Jesus and Mary Chain, C86, indie, lo-fi, etc’. Bowie wasn’t the only stadium-filler to acknowledge their influence, with the likes of U2 and REM doing the same.

Whilst Lou Reed was the band’s principal songwriter, Cale had a huge hand in shaping the sound of the first two Velvet Underground albums. ‘The Velvet Underground and Nico’ and ‘White Light/White Heat’ certainly didn’t shift units but they’re indisputably two of the most influential records in rock ‘n’ roll history.

Subversive

Bowie again: ‘To me, the sound of the band was John Cale. That was confirmed a few years later when I worked with Lou on (his solo album) ‘Transformer’. John was the subversive element of the band, one of the most underrated musicians in rock history. That guy is a danger, a true character’.

Cale’s first wife, fashion designer Betsey Johnson agrees. ‘He had so much charisma. He had the balance of the Velvet Underground charisma. Lou without John, it wouldn’t have had the edge. John gave it that romantic…. I mean, the sound of the Velvet Underground was John. The words and the music was Lou but it was those weird nails on the blackboard sounds and the holding of the notes and that La Monte Young/Terry Riley (Riley was another avant-garde musician who favoured drones and long form improvisation – he and Cale made an album together in 1970) preface to The Velvet Underground – that cold edgy Wales edge. And John just visually was the person I always looked at’.

‘Sounds as stark as black and white stripes – bold and brash, sharp and rude, like the heat’s turned off and you’re low on food… how in the world were they making that sound?’ asked Jonathan Richman in his 1992 song ‘Velvet Underground’. The answer, basically, was John Cale.

By 1968 and the making of the White Light/White Heat album, the relations between band members had become fraught. Without Cale, Tucker or Morrison’s consent (or even knowledge) Reed sacked Warhol and brought in Steve Sesnick to replace him. ‘Sesnick became an apologist for Lou. He was a yes-man who came between us. It was maddening… Before, it had always been easy to talk to Lou but now you had to go through Sesnick’ Cale later reflected.

By 1968 Reed decided that as well as Warhol, he’d also had enough of ‘cold, edgey Welsh edges’ and was going to prioritise straightforward sounds and pretty songs in his quest for rock superstardom.

In the September Cale played his final gig with the Velvet Underground in Boston. ‘Lou gave Moe and Sterling an ultimatum’ he told Melody Maker’s Allan Jones in 1993. ‘Either I was out of the band or there was no band… we were supposed to be going to Cleveland for a gig and Sterling showed up at my apartment and told me I was out. It was the way Lou did things – he always got other people to do his dirty work for him’.

Although Cale concedes he wasn’t entirely blameless in regard to his deteriorating relationship with Reed, he was also rueful in telling Jones of his disappointment over ‘our inability to face up to the responsibilities that attach themselves to people who dare to be different… in that regard, we let ourselves down’.

His departure left Moe Tucker ‘really sad. I felt really bad. And of course, this was gonna really influence the music, ‘cos John’s a lunatic! I think we became a little more normal, which was fine – it was good music, good songs. It was never the same though. It was good stuff, a lot of good songs, but, just, the lunacy factor was… gone’.

Real Cool Time

Never one to rest on his laurels, Cale got to work as a producer and arranger, starting with Nico’s second solo album ‘The Marble Index’; ‘The arrangements I did were really borderline European avant-garde music . It was the closest thing to contemporary European classical music that I could do’. Although it’s release went virtually unnoticed in November 1968, it was a record that was to heavily influence what eventually became known as goth, a punk subgenre more than a decade away from coalescing.

Then head of Elektra label Jac Holzman took Cale to see his new signing The Stooges because he wanted him to produce their debut album. ‘Here was a band that sounded like the Velvet Underground so it wasn’t even a proper production job with them. You just pressed the button marked ‘record’ and let them get on with it’. ‘The Stooges’ was a kind-of primer for what was to become known as punk. When The Sex Pistols covered ‘No fun’ seven years later that link was made stark.

The Velvet Underground and Nico, White Light/White Heat, The Marble Index, The Stooges… just the four seminal, way-ahead-of-their-time albums under his belt by the age of 27 then. ‘As a solo artist he’s nearly unsurpassable to me’ says James Dean Bradfield but we haven’t even got to that yet.

Music for a new society

1970 saw the release of the album ‘Vintage Violence’. Although Cale writes of his solo debut dismissively in his autobiography, Super Furry Animals’ singer Gruff Rhys considers it ‘a really interesting pop record’. He expanded on that in an interview with The Quietus; ‘Sound & Vision’ by Bowie is a complete lift of ‘Cleo’…it’s obviously a record that seeped into people’s collections so a music fan like Bowie would have been aware of it’.

As a solo artist, he perhaps hit his stride with his run of albums from Paris 1919 (1973) to Fear (1974) and Slow Dazzle (1975). Despite containing gorgeous ballads, there are moments that preempt punk in their desire to shock and the raw anger on display.

‘I find it intriguing that he writes songs like Gun or Fear is a man’s best friend (from the Fear album), or the cover of Heartbreak Hotel (described by punk priestess Siouxsie Sioux as sounding ‘completely evil… reptilian… it gives me tingles’) which have an undercurrent of terrifying anger, and then he can counter them with some of the most beautiful music anyone has ever written, things like The Endless Plain of Fortune, Amsterdam and I Keep a Close Watch (described by music journalist David Bennun as ‘very nearly more beautiful than the human heart can bear’) muses James Dean Bradfield. ‘Sometimes he manages to still the rage within him and navigate himself to calmer waters’.

Released in 1982, ‘Music for a New Society’ is an album Cale described as ‘preoccupied with the terror of the moment’. The process of making it appears to have been both painful and necessary; ‘Apart from a couple of poems Sam Sheperd sent me, the songs were completely improvised in the studio. It was like method acting. Madness. Excruciating. I just let myself go. It became a kind of therapy, a personal exorcism’. Asked by the BBC if he ever felt suicidal he replied ‘there were moments, definitely moments… the characters in the songs, they all tended to feel trapped and that’s what I was describing – the pressure on them. To figure out what the next step was’.

After the pain and confusion of around twenty years of heavy drinking and drug abuse (particularly cocaine) Cale realised ‘the only way to go was back up. I started to look for daylight again’, getting clean after the birth of his daughter Eden Myfanwy in 1985. In an astonishing act of willpower Cale sobered up pretty much overnight. ‘The sullen years’ as he refers to them, were over.

‘I channelled fitness… I took up squash – the most taxing, demanding sport I could think of’. Later on, he was to favour running up the staircases of skyscrapers. Nearly forty years of sobriety means Cale looks much better than any man about to hit 80 has any right to. Or as he amusingly deadpanned himself on ‘A dream’, a song made up of lines from Andy Warhols’s diary, ‘then I saw John Cale – he’s been looking really great’.

Parallel to his solo career Cale also kept up the collaborative work, producing the debut albums from Jonathan Richman and The Modern Lovers (‘his whole thing was to try to continue what the VU started. It was a little eerie but there was a sense of humour to what he did that I found very appealing’), Patti Smith’s classic ‘Horses’ in 1975 (‘she was a creative volcano that kept erupting. We were at loggerheads a lot of the time’) and Happy Mondays ‘Squirrel And G-Man Twenty Four Hour Party People Plastic Face Carnt Smile (White Out)’ in 1987 (‘I honestly thought at least one of them was going to die on me…it was frightening… they were totally out of control’)

Following the positive response to ‘Songs for Drella’, the four original members of The Velvet Underground reunited in 1993 to tour, including stadium dates supporting U2 and a fraught appearance at Glastonbury festival. The old tensions between Cale and Reed were coming to a head again. ‘I looked at Lou on the plane from England to the US and I realised: this guy is empty. He does not know where to draw the line… it was the end of a very fruitful relationship. A poisoned one but a very fruitful one’.

So the chance to tour the States and record an Unplugged set for MTV was jettisoned, Reed’s ego yet again proving too obtrusive. There was a brief reunion to accept their induction to the Rock ‘n’ Roll hall of fame in 1996, where a clearly emotional Reed, Cale and Tucker paid tribute to the recently deceased Sterling Morrison with a new song called ‘Last night I said goodbye to my friend’.

Do not go gentle into that good night

When Cale says the word ‘aaaaand’ you can clearly hear the drawl of a man who’s spent nearly six decades in the States, but on ‘Corner of my sky’, a collaboration with Rhuddlan-born electronic musician Kelly Lee Owens, the 78 year old sounds more Welsh than ever.

Owens explained how the collaboration came about on Radio 4 arts show ‘Front Row’; ‘I wrote the music and for some reason the sounds connected to the Welsh landscape. Then I needed another storyteller to put another spin on it and I thought of John’s incredible commanding voice… I’d love him to read me a story! So I asked him about his relationship with Wales and to go into that… and the land… and he delivered this beautiful performance. It was only later that I found out he hadn’t sung or spoken in Welsh on a record for thirty years so I felt really honoured’.

Former Archbishop of Canterbury Dr. Rowan Williams was also a guest on the show and seemed genuinely impressed by the track; ‘I think what’s really important is it’s a such of puncturing of a false romanticism or sentimentality about the Welsh identity…there’s a real innovative streak and real radical streak and a very strong pastoral element to it’.

Talking of divinity, Cale wrote in his autobiography that ‘belief in a divine right to success, regardless of ability, hard work or effort, was a part of the American Dream I had never bought into’. When he states that ‘it’s the work that’s important’, it betrays a temperament that’s clearly still Welsh to the core.

And work is something Cale has done plenty of. From the soundtrack to the film ‘American Psycho’ to a ballet based on the life of Nico to ‘Words for the dying’, a choral symphony using the poems of Dylan Thomas and much, much more.

The workload is something that leaves James Dean Bradfield impressed; ‘The length and breadth of his career as an artist is just stunning. It’s also got to be said – with a fair bit of Welsh self-loathing – that it’s slightly incongruous that someone from Wales could batter down the doors in the way that he did and promote himself fully into so many different worlds so successfully’.

For Cale, his Welshness is something he’s always struggled with. Like Dylan Thomas before him, he’s endured a complicated relationship with his homeland. ‘I’ve never thought about Wales as anything other than something to get away from… and that’s a really rough thing to have to rationalise to yourself..’ he told the website Noisey. But in a 1998 BBC documentary, in which he returned to Garnant, he conceded that ‘the beauty of the place is something you can’t get away from’.

Besides, the push and pull, the attraction to both the darkness and the light, the desire to escape from something you know you can’t really escape from, is one of the defining characteristics of his music.

And Wales is always there. ‘After my parents died (his father in 1983, mother in 1990) I became closer to my other relatives’, he told the Guardian. ‘I go back as much as I can. I have a cousin in Cardiff and when I look at pictures of myself and my cousin it’s like looking at two versions of my father – male and female. I have some relatives in Pembroke who I see every once in a while. It’s very warm’. On his 2016 album M:FANS, a reworking of Music for a New Society, he put an old recording of his mother singing on his answering machine on the prelude, partly because ‘my daughter had never heard her voice’.

Despite being born and raised on the east coast of the USA, Eden’s Welsh heritage is obviously important to her. She’s the co-founder of digital media agency called Hiraeth Media, got married in 2017 wearing a woolen shawl and gave her guests carved wooden love spoons at the Connecticut ceremony. Cale played ‘I Keep a Close Watch’ with Eden sat beside him at the piano, something she describes as ‘a special moment for me and my dad’.

Asked by American radio station KEXP if he enjoyed singing as a child Cale replied, ‘you’ve got to remember you’re talking to a Welshman…we all sing at the drop of a hat’. But it’s not just that he sings, but the way he sings that feels significant. ‘It’s incredibly reassuring to hear someone with such a direct Welsh voice in music that doesn’t resort to pastiche’ says James Dean Bradfield. ‘It’s almost like it’s something carved out of the landscape, an artefact that’s been found and passed down. It seems utterly steeped in the tradition of male voice choirs, of the very mournful music that Wales seems so intrinsically linked to. You can’t really explain it; that’s just how it sounds. His voice isn’t there to explore new universes or styles – it just tumbles out like a big slab of granite, fully formed. It’s equivalent to Lee Marvin’s acting, an unstoppable force. He doesn’t have to do much to convince you because the weight of his talent and his fantastic controlled rage is there for you to see all the time’.

‘I think as a musician still working, he offers an inspirational path as to how you can still experiment’ Gruff Rhys says. ‘The Super Furries collaborated with him for the film Beautiful Mistake (‘Camgymeriad Gwych’, director Marc Evans’ 2000 film for S4C in which Cale collaborated with young Welsh musicians) We got to be his backing band. It was so interesting, like an out of body experience’ the teenage Velvets obsessive told The Quietus. ‘I think it was interesting for him as he hadn’t had band practice in the Welsh language since the early-1960s or something’.

Lou Reed died in 2013 after his body rejected a transplanted liver. Cale considered his passing ‘a big disappointment because I heard Lou had started drinking again and I just thought ‘what’s going on here?’ …the one thing we were both adamant about was that the work was really important… he started drinking again which suggested he didn’t care about the work anymore…’. They may have been born in the same week but Cale has already outlived Reed by close to a decade. It’s been a fruitful time too.

At a spectacular 2016 show at Cardiff’s St David’s Hall to launch that years Festival of Voice, Cale was joined onstage by a choir, a chamber orchestra, Michael Sheen (who recited Dylan Thomas’ ‘And Death Shall Have No Dominion’) and Charlotte Church (who turned in an operatic ‘Gravel Drive’, a song Cale wrote about the guilt involved in leaving people behind). ‘Every time I come back I rejoin you’ he told the crowd, clearly relishing his role as the nation’s elder statesman of song.

Welsh language

Asked by Kelly Lee Owens in 2020 if there were still things he wanted to explore creatively that he doesn’t feel he’s been able to before, he replied ‘the Welsh language… its humour is much easier for me to understand now than when I grew up. Strangely, I can approach the language in a barrel roll fashion by blindly opening a dictionary and firing away as the words trip out’. When Owens inquired about his relationship with his homeland Cale ruminated that ‘the further away Wales appears in my memory, the more complicated its images and demands become on my understanding of my past’. Not that he’s one to particularly dwell on such matters anyway. As Gruff Rhys says ‘I’ve been lucky enough to work with him a few times and I’ve realised he’s got no interest in nostalgia – he’s always moving on’.

‘I’m from a working class background. When people say ‘you’ve had your time’ I tell them to get lost. There’s a lot of work to be done. I still have ideas. I still hear things that make me jump up. Music has always been exciting to me’.

Penblwydd hapus John. Here’s to the next decade.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

A beautiful read, thank you.

Superb article, diolch!! Perhaps I’ll add……..Cale, Eno, Fripp, Scott Walker. Essential?

Certainly in the pop world, we may never see the like again, due to educational fail.

Hope I’m wrong.

What a wonderfully written and informative article on one of the most underrated musicians and influences in modern music history.