Queer Square Mile – two centuries of diverse Welsh storytelling

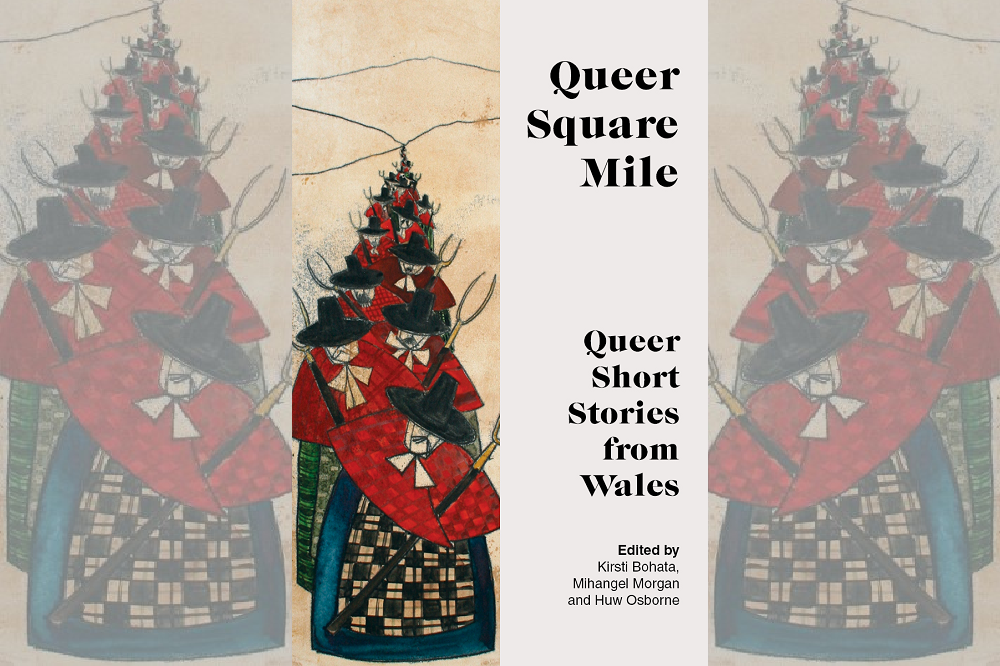

Queer Square Mile is a ground-breaking anthology of queer Welsh writing edited by Mihangel Morgan, Kirsti Bohata and Huw Osborne and published by Parthian.

The volume makes visible a long and diverse tradition of queer writing from Wales, dating back to the 19th Century and spanning genres from ghost stories and science fiction to industrial literature and surrealist modernism.

In anticipation of the release of the collection at the end of February, the historical and social context of the work is considered by the editors in this introduction to the work.

Mihangel Morgan, Kirsti Bohata and Huw Osborne

‘there was a man in this place one time by the name of Ned Sullivan, and a queer thing happened to him coming up the valley road from Durlas.’

–Frank O’Connor,

The Lonely Voice: A Study of the Short Story (1962)

Frank O’Connor did not share our contemporary notion of ‘queer’ when he opened his seminal book on the short story with these words. His point was that the short story emerged from communal story-telling tied to a local sense of ‘this place’ – one’s milltir sgwâr [square mile] as it is called in Wales.

The word ‘queer’ has changed in meaning over time. From meaning ‘odd’ and then being used as a term of abuse to describe mainly gay or effeminate men or mannish women, it has been reclaimed. It is now a positive and powerful term to describe LGBT lives and cultures. In a broader sense, it also refers to cultural and critical thinking that challenges received norms, troubles assumptions and creatively upends conventions.

The short story is particularly suited to exploring such queer ex-centric experiences and perspectives. Frank O’Connor explains how, over time, communal, local and usually oral stories—which drew on and reinforced a sense of place and shared experience—evolved into a modern ‘private art intended to satisfy the standards of the individual, solitary, critical reader’, an art particularly conducive to the outsider experience.

The stories in this collection echo O’Connor’s contention that the short story ‘has never had a hero. What it has instead is a submerged population group … outlawed figures wandering about the fringes of society [… instilling] an intense experience of human loneliness’. It favours ‘tramps, artists, lonely idealists, dreamers, and spoiled priests’; it is ‘romantic, individualistic, and intransigent’. In its ex-centric perspectives, it has the ability to unsettle, but also to show alternative ways of living.

Pure tale-telling quality

About a decade before O’Connor’s study, Rhys Davies—who features prominently in this collection and who certainly shared some of our notion of ‘queer’—described the short story in similar terms: ‘In contrast to the novel, that great public park so often complete with great drafty spaces, noisy brass band and unsightly litter, the enclosed and quiet short story garden is of small importance and never has been much more.’

This private, intimate and cultivated space needn’t appease the views of the wider public market of the novel. Unlike O’Connor, however, Davies sometimes claimed, as he did in a letter to the American author and editor Bucklin Moon, that the short story never entirely lost the qualities of its ancient and communal roots, so that the private and ex-centric tale may also, paradoxically, be the national one:

‘Short stories, like one’s first love, have always remained sweet to me. I like the spread and space of novels, in which one can do much more secret and indirect teaching—and even preaching—and handle themes which make one feel a bit like God, but in the short story one can be, so to speak, more human. There is a fire-side, pure tale-telling quality in short stories and they can convey with much more success than the novel the ancient or primitive, the intrinsic flavour of a race or people.’

Davies associates short stories with the personal intimacy of ‘one’s first love’ and opposes them to the God-like preaching of the novel. This intimacy, furthermore, is also the fire-side intimacy of a people connected to a place and a past (which Davies expresses in racialised assumptions of his time).

Here the short story is conceived in the tension between public communities and private selves, national belonging and intimate love. So the queer short story of Wales is often doubly ex-centric, expressing national and sexual marginalities that are not always easily reconciled.

The short stories collected here span nearly two hundred years. The earliest—anonymous—contribution is from 1837, the year of Queen Victoria’s coronation. The most recent are three new, previously unpublished stories by Dylan Huw, David Llewellyn and Crystal Jeans.

Sexuality & identity

Understandings of sexuality and gender have transformed more than once during in this period. In the nineteenth century, gender rather than sexuality was the more rigidly policed element of identity, and so it is apt that ‘The Conquest, or a Mail Companion’ (1837) portrays dashingly romantic female masculinity in a woman who remains a ‘hero’ even after we know she is not the gallant young man her companion believes her to be.

Gender is also the focus of Amy Dillwyn’s ‘One June Night: the Story of an Unladylike Girl’ (1883), in which a tomboyish girl (a staple figure of queer writing) tries to fill her father’s shoes while reaching across class boundaries. By the end of the nineteenth century, the work of sexologists such as Havelock Ellis and Sigmund Freud had transformed understandings of sexuality and identity.

Sex was now more than an act or even a matter of sexual orientation: sexuality itself had become an identity and homosexuality a pathological form of gender and sexual ‘inversion’. Homosexual acts between men were illegal in Britain throughout the nineteenth century, while sexual relationships between women were misrecognised and rendered invisible. As the twentieth century got underway, queer women were increasingly under suspicion while queer men lived at the risk of imprisonment, blackmail, loss of employment, loss of family, and public shaming until well into the twentieth century.

The repressive environment, however, also led to alternative spaces of desire and sociability, such as gay balls (as seen in Davies’s ‘Wigs, Costumes, Masks’ (1949)), bachelor apartments (as seen in ‘The Collaborators’ (1901)), lesbian domesticities (as seen in ‘A Modest Adornment’ (1948) and ‘Nadolig/Christmas’(1929)), erotic tourism (as seen in ‘The Stars Above the City’ (2008)), cruising parks and ‘cottages’, gentlemen’s clubs and gay and lesbian bars (as seen in ‘Muscles Came Easy’(2008)).

It also led to literary creativity as writers turned to coded ways of expressing same-sex desire – repeated use of the word ‘rhyfedd’ meaning ‘odd’ and ‘strange’ in Kate Roberts’s stories of intense female friendship, for instance, invites the reader to imagine what is not, or cannot be, articulated.

The situation began to change in 1957 with the high-profile publication of the Wolfenden Report, which recommended the decriminalisation of homosexuality between two men in private. By 1967, two years before the Stonewall Riots in Greenwich Village, New York, this recommendation was finally passed into law – in large part due to the reasoned and eloquent support and advocacy of Leo Abse, Labour MP for Pontypool.

In the shadow of the pulpit

While a Welsh MP was instrumental in changing the law, and Wales benefitted as part of the UK, it is helpful to understand something of the specific cultural contexts of Wales. The short stories collected here derive from two distinctive linguistic cultures, though the stories, like the cultures, share many points of correspondence.

Meic Stephens’s Cydymaith i Lenyddiaeth Cymru [Companion to Welsh Literature], says that ‘It is impossible to begin to understand modern literature in Wales [in Welsh] without paying appropriate attention to the contribution and influence of Nonconformism, and the reaction to it.’ English-language literature from Wales also contributed to and was influenced by Nonconformism, but there is a much longer Welsh-language tradition of reading and writing ‘in the shadow of the pulpit’.

At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, Wales was still a predominantly Welsh-speaking country, working-class and chapel-going. People learned to read in the Sunday schools and most reading material was religious in nature. This was due in large part to the fact that the few who had the necessary education and leisure to write in Welsh tended to be mostly ministers of religion.

Their work in Nonconformist women’s publications such as Y Gymraes [The Welshwoman] and Y Frythones [The Britones] was often moralistic in tone, on themes of temperance or, in the mid-nineteenth century and in response to explosive claims in a government report that Welsh women were sexually and morally lax, on the theme of the Virtuous Woman.

The novels of Daniel Owen in the late nineteenth century and Kate Roberts’s first collection of short stories published in 1925 were two watershed moments, with Saunders Lewis claiming that the short story in Welsh had ‘taken a definite step into the world of artistic creation’.

Roberts was a freethinking individual, but even her stories deal with the matter of sex indirectly and arguably all the more finely for that. The lyrical opening sequence of one of her great novels Traed Mewn Cyffion [lit. Feet in Stocks, or Feet in Chains] (1934), for instance, opts for a subtle and coded way of telling the reader that her recently married protagonist has just become pregnant.

Sexual nature of humanity

Reticence in the treatment of sex and sexuality was perhaps unsurprising given the scandalised reaction to bolder representations. Prosser Rhys’s treatment of the sexual development of a young man, including a (negative) reference to a same-sex experience, had scandalised the Eisteddfod in 1924.

Though it won the highest honour, the Crown, the poem was not published again in his lifetime. In 1930, Saunders Lewis published the modernist novella Monica, full of brooding dark passion, in which the eponymous character’s erotic fantasies and strong sexual desires are the focus of the story.

Lewis appealed to the precedent of the hymn-writer William Williams Pantycelyn who had dramatically depicted the sexual nature of humanity in its many variations in Bywyd a Marwolaeth Theomemphus [The Life and Death of Theomemphus] (1764) and Ductor Nuptiarum (1777).

In reminding readers that a writer as revered as Pantycelyn, whose hymns were sung in chapel every Sunday, had written about sex as part of life, Saunders Lewis hoped that this would lead the way to the theme being used more freely in poetry and fiction in Welsh. Indeed, in an analysis of Oscar Wilde, Lewis saw connections between sexual expression and creativity, remarking that ‘The years of his intercourse with Alfred Douglas and with London “renters” were the years in which he wrote his brilliant comedies’.

Pennar Davies’s direct story of same-sex desire, ‘Y Dyn a’r Llygoden Fawr’ [The Man and the Rat], was published in the journal Heddiw in 1941, but for the most part Lewis’s hopes were not fulfilled until later in the century, and the word ‘pechod’ [sin] continued to be used as a synonym for sex.

Pockets of tolerance may have existed in some communities, as Daryl Leeworthy’s A Little Gay History of Wales has shown, but for many, despite decriminalisation in 1967, the stigma of homosexuality (especially for gay men) continued across Wales and the UK.

Political activism

The AIDS crisis in the 1980s (addressed in John Sam Jones’s ‘Eucharist’ (2003)) led to widespread fear and vilification of gay men, as well as further restrictive legislation by Margaret Thatcher’s conservative government, including Section 28 of the Local Government Act (1988) prohibiting the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality in schools (as seen in ‘The Wonder at Seal Cave’(2000)).

By the 1990s, partly arising from the political activism born from protesting the poor Conservative response to the AIDS crisis, a more public and organised LGBTQ consciousness began to take shape in Wales.

The word ‘queer’ took on its current political and theoretical meanings; Stonewall Cymru was established in 2003; and the public imagination of Wales underwent a queering through twentieth- and twenty-first-century cultural industries, education reform, legal reform, and civic and national revitalisation.

This history is not, however, simply a case of ‘progression’ from closet to pride parade. As seen in the later stories in this collection, this latter era of reform is not one of straightforward liberation or progress but increasing complexity and persistent challenges.

Queer Square Mile is published by Parthian on the 28th of February and can be pre-ordered here…

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Can you please stop using the word queer? It is derogatory.

I am working hard in my school trying to teach children not to use language like that. Adults should set an example, not normalize slurs.

In the context of a school you are doing the right thing,but Nation Dot is aimed at adults.

Thanks for the compliment, and I can see your point. However, I do believe that slurs are wrong with adults too. I find that word as offensive as the ‘n’ word.

I think the ‘q’ word has been normalised by some LGBT people, although not by others. This has created a context where people wrongly think it is acceptable as a way to describe gay people that way.

On the plus side, I am encouraging my students to read Nation.Cymru. Overall they are quite receptive.