Review – Adra by Simon Brooks

Ifan Morgan Jones

This isn’t so much a review of Simon Brooks’ new book, Adra: Byw yn y Gorllewin Cymraeg [Home: Living in the Welsh-language West] as a discussion of it.

Because, as an intensly political book, there doesn’t seem to be much point in judging it as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ as much as discussing and dissecting what it actually has to say.

So I’ll keep the ‘review’ part of this article short. It’s enough perhaps to say that it’s an important and timely book, very well-written, and extremely funny in parts. I very much enjoyed reading it, and you will too.

There, that’s the review bit done!

Whether you agree or disagree with Simon Brooks, his work is always unique and interesting. His last book, Why Wales Never Was, was so interesting I spent large parts of my PhD dissecting it.

His thesis then was that the Liberal Nonconformists of the 19th century had held back the development of Welsh nationalism at a time when much of the country was Welsh speaking.

I disagreed, partly because I saw in these chapels the seed of independence that would blossom into national institutions such as our own universities, national library, museum, and eventually devolution.

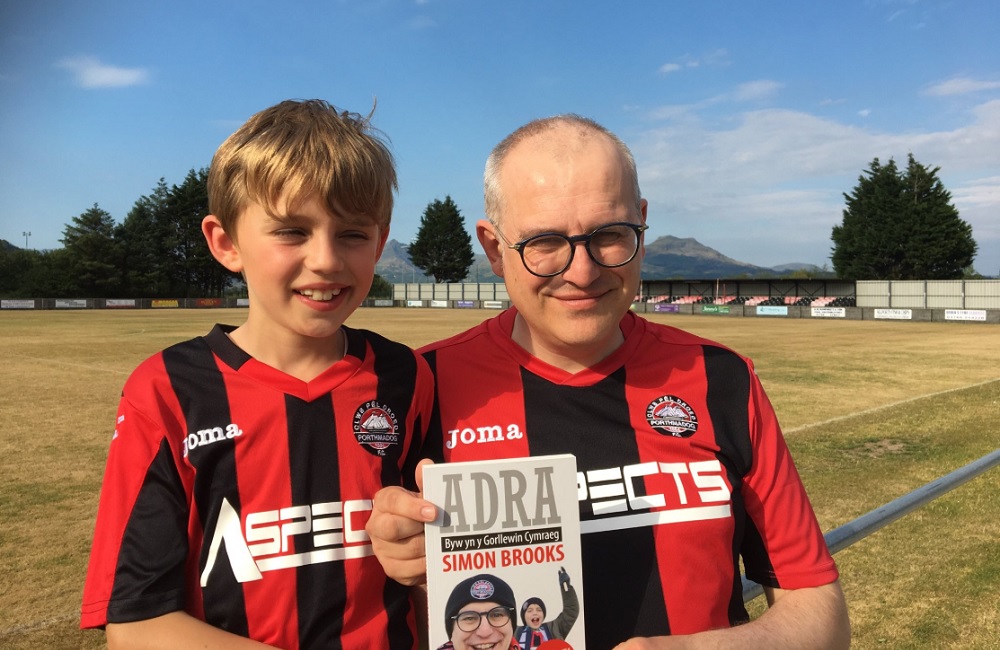

How is this relevant to Adra? Because it is a book mainly concerned with an institution – the Porthmadog football team in this case – and the independence it gives the people of a town that have otherwise had control taken away from them.

Cynicism

Brexit is only mentioned in passing in this book but in many ways it is always there, just on the horizon, like a brooding thunderstorm. Because it is ultimately a book about the frustrations of a town that has been left behind, and their desire to ‘take back control’ for themselves.

The theme that runs through the book are that decisions made by centralised authority – whether those decisions are made in London, Cardiff or the Plaid Cymru-run Gwynedd Council in Caernarfon – take away the autonomy of places like Porthmadog.

For instance, a decision by Gwynedd Council to force Porthmadog Town Council to pay for the upkeep of public toilets is a “political catastrophe that intensifies the feeling that we are being exploited by forces from outside”.

According to Brooks, being moved by forces beyond their control has made the community cynical, and as a result they don’t, or don’t feel they can, take steps to improve their own lot.

The football team is at the heart of the community because that it’s the only thing the working-class people of Porthmadog are trusted to run themselves.

Interestingly, he compares the football team with a church more than once. Which is why I think he might like to revisit his condemnation of the nonconformist churches of Wales’ industrial frontier in Why Wales Never Was!

Gwyneddlaetholdeb

Brooks is an interesting and unique voice amongst Welsh nationalists because he, almost uniquely among them, isn’t a massive fan of devolution.

The reason is that, according to his thesis, north-west Wales has since devolution become an internal colony of Wales.

Wales has long been portrayed as a colony of England, but Brooks’ argument is that Wales is now the UK in miniature, with Cardiff the dominant, colonising force.

He argues this on the basis that very little investment is made there to improve people’s lives but a key good – young men and women – are extracted to work in Cardiff.

As one of three brothers who left Gwynedd, enchanted like moths towards its bright lights of Cardiff, it’s difficult to argue against the validity on his claim.

Not only does Cardiff not invest in Gwynedd but, like London’s relationship with Wales, doesn’t really understand it either, Brooks says.

Not even those who were brought up in Gwynedd and moved to Cardiff understand it, as they haven’t had to experience the grinding poverty which characteristic of the lives of many adults there.

For Brooks, then, Gwynedd is itself a country. He might best be called a Gwyneddlatholwr – a Gwynedd nationalist.

In the same way as Welsh nationalism is a reaction to political, economic and cultural power being inexorably sucked into London, Gwynedd nationalism objects to the same process ongoing in Cardiff.

Tolerance

More controversially, perhaps, the book can also be read as a defence of the largely working-class, white communities and people who have lived in the same place all their lives.

These are the ‘people from somewhere’ that have come under fire since Brexit and Trump – although it should be pointed out that the Welsh-speaking west of Wales voted against Brexit.

What Brooks learns from his travels around the north and west of Wales with Porthmadog is that every community is different, and deserves to survive, even if it is mostly made up of middle-aged white people.

Brooks isn’t a fan of Jeremy Corbyn’s unionist leftism which seems to embrace every minority group but those indigenous to the UK.

He is at pains to point out, however, that there is nothing xenophobic here. The working class Englishmen in Port belong to the town to a greater degree than a Welsh-speaking Welshman who has moved away to live in the big city.

Despite the lack of diversity within these ‘left behind’ communities, beyond linguistic diversity, there is a fundamental tolerance of difference there, he says.

Divided

Although a Plaid Cymru town councillor, Simon Brooks comes at Wales and Welsh nationalism from a radical conservative perspective which is very different to the current leadership of the party.

His work is very much in the intellectual tradition of Saunders Lewis, who is often branded ‘right-wing’ in nationalist circles – a label Brooks rejects here.

It’s very difficult to disagree with his thesis that devolution has not served Gwynedd well.

Where I might disagree, however, is that I think there is no real difference between the challenges facing Gwynedd and much of the rest of Wales.

All of Wales has working-class communities suffering from a poverty not just of wealth but also ambition.

All of west Wales is dealing with the erosion of its linguistic identity, a process that is going on significantly faster in places like Carmarthenshire.

There is also a danger in that by pushing a form of Gwynedd or North Wales nationalism we drive a wedge into what is already a country divided between north and south.

The answer, in my opinion, is to push for our devolved institutions to do more for every part of the country, rather than arguing that any particular area has been singularly ill-served.

I do however see an argument for giving the west of Wales more autonomy to tackle some of the unique linguistic challenges facing the Fro Gymraeg.

But while I don’t agree with everything, that’s part of the enjoyment of reading Brooks’ work. He is always challenging and isn’t afraid to voice opinions he knows will be unpopular – an essential trait in a linguistic community where everyone seems to know each other.

As an autoethnographic study of one community and the football team that binds it together, this book is second to none.

It should make for an interesting discussion at the National Eisteddfod – which has this year landed at the mecca of the Welsh-speaking Gwynedd expat in Cardiff Bay!

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.