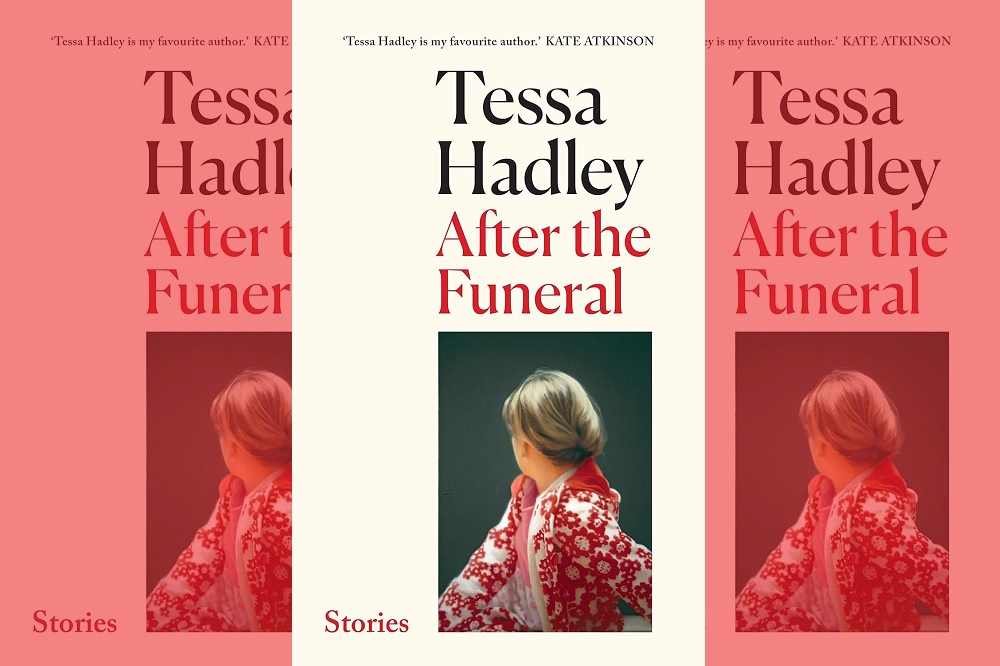

Review: After the Funeral by Tessa Hadley

Sarah Tanburn

Grief, and its place in the stories of our lives, relies on memory. That contingent, unreliable sense of what happened and why. It is not only the title story of this collection which begins with death, but none end that way.

Rather Tessa Hadley extends intimate invitations to consider for yourself what happens next. Is Charlotte, with her pale-green skin, pregnant? Will Diane unleash the sought-for passion as unwisely as Emma Bovary, or continue to hover in the spare room? Can Robyn learn happiness?

Such questions linger because of Hadley’s skill at portraying her characters with such intensity, in so few words. The unnamed narrator’s banishment to school in England, the anguish of his time there, was such that ‘he hadn’t allowed himself to imagine that [his beloved sister] might have felt left behind, cheated.’

The bride’s clear-sighted daughter says of the groom at ‘My Mother’s Wedding’, ‘Mum thought he was other-worldly, like the Celtic saints, but I knew he was just an intellectual.’ Such prose, conveying wicked insight, is part of the fun of reading these tales.

It remains fashionable to use terms such as ‘domestic’ or ‘interior’ to disparage such realist work focused on women’s lives, the experiences specific to care (of children, elders, the incompetent), of puberty and awakening. For writing with such attention, Hadley is often likened to Elizabeth Bowen (a writer I loved in my youth and of whom I am glad to be reminded) or Anita Brookner.

I found these stories evocative of Barnes’ ‘Sense of an Ending’, the feeling of unreliability and elegy combined with a reshaping of life in the face of belated understanding. The difference is that Hadley’s characters pick up and carry on.

Geography and its limits

Tessa Hadley has lived much of her adult life in Cardiff, but Wales tends to be the distant view, mountains glimpsed across the whispering Severn or the brown swirl of the Bristol Channel. The exception is that wedding, held in an uproarious, extended family who have settled in Pembrokeshire, with feral, intertwined children, self-chosen names, beautiful women and lots of intoxicants.

Yet many of the tales are set nowhere specific, save suburban Britain. The scruffy edges of towns built around railways, faded seaside resorts which might be Rhyl or Hastings, the detachment of universities or sheltered housing.

The amorphous ‘North’ is useful here – maybe Sheffield, Leeds, Manchester or Liverpool – though I have the feeling that Hadley knows exactly where the action is and has left it to us to fill in the picture from our own memories. We could be almost anywhere, save for the central importance of class in how her characters view and shape their lives.

In this sense, Hadley is clear-eyed about the texture of so many British interactions; down-at-heel middle-class Margot is horrified by the attention of a working carer. Serena, living her alternative life in London, has somehow let the side down. Elsewhere or at other times, perhaps the gradations of difference are not so minutely examined, but they are still present.

Maybe somewhere the questions would be: are the neighbours sufficiently devout? Have they hung their laundry out on a Sunday, or worn just a little bit too much gold? It is easy to find the brambles in the thickets of human relationships.

The general and the particular

The specificity of description combined with blurred geography captures the universality of Hadley’s work. This may seem a strange claim given my comments on class. She herself has said (in an interview in the New Yorker) that she is ‘very much not a universalist. I don’t feel that you can strip away the extras and there’s a sort of universal same experience that everybody goes through.’

Yet I would say that the ‘universal’ label is often applied to male writers discoursing on love, sexuality, adolescent angst and legacies, but disallowed for women. It is in this sense that Hadley is exploring what happens next in our quotidian lives once disaster has occurred or we seize the chance for change. She asks us to imagine not only what her characters will do, but what we do when such moments come to us.

They will of course. They may not be in the exact shape she offers. Our fathers, in general, will not die in the company of an unknown lover while travelling abroad, as two do here. Our own beloved (we hope) will not fall anew in love with her dead husband.

But those betrayals, those losses and victories will come our way. And while they may seem quiet, even insignificant compared to the catastrophic wars flickering in our living rooms every night, for each of us, those incidents, however undramatic they are, will shape our own lives.

Hadley emphasises that such moments not only guide what we do, but how we tell the story of what we did, of who we are. For Heloise, discovering Delia’s role in the past twists the kaleidoscope on her own history. Valerie’s rescue of Robyn creates a new narrative for her future. And, Hadley asks, who are we if we are not that narrative? How far can we trust ourselves if we find our stories rest on lies, misunderstandings or even a simple joke?

Prizes and prestige

Tessa Hadley has won the Hawthornden, Edge Hill and a Windham-Campbell Literary Prizes as well as being longlisted twice for the Orange Prize. She is the Welsh writer most frequently published in that pinnacle of short fiction, the New Yorker.

She is a Fellow of both the Royal Society of Literature and a previous Chair of the editorial Board of the New Welsh Review. Despite such prestige, she is one of Wales’s unsung literary treasures, rarely profiled or reviewed in the media of her home country.

Perhaps it is all too easy for some readers and critics to dismiss Hadley’s acute psychological examination as ‘women’s fiction’, and therefore not something for serious, muscular, masculine readers. You will do yourselves a disservice if you pass up on her work on such a trivial basis.

Rather this collection captures, often with humour and always with precision, a series of circumstances and opportunities in the lives of humans. She writes with such clarity, making such story-telling look effortless, that the reading is a joy and delight on these dark autumn afternoons.

After the Funeral by Tessa Hadley is published by Jonathan Cape and is available from all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Perhaps Tessa Hadley is not mentioned by the Welsh is because she does not mention them.Nobody winges about Ken Follett not bein lauded in Wales,he is a Welshman but an English author,the same may well be said of Ms Hadley.