Review: Byd Gwynn offers us two titans, one writing about the other

Jon Gower

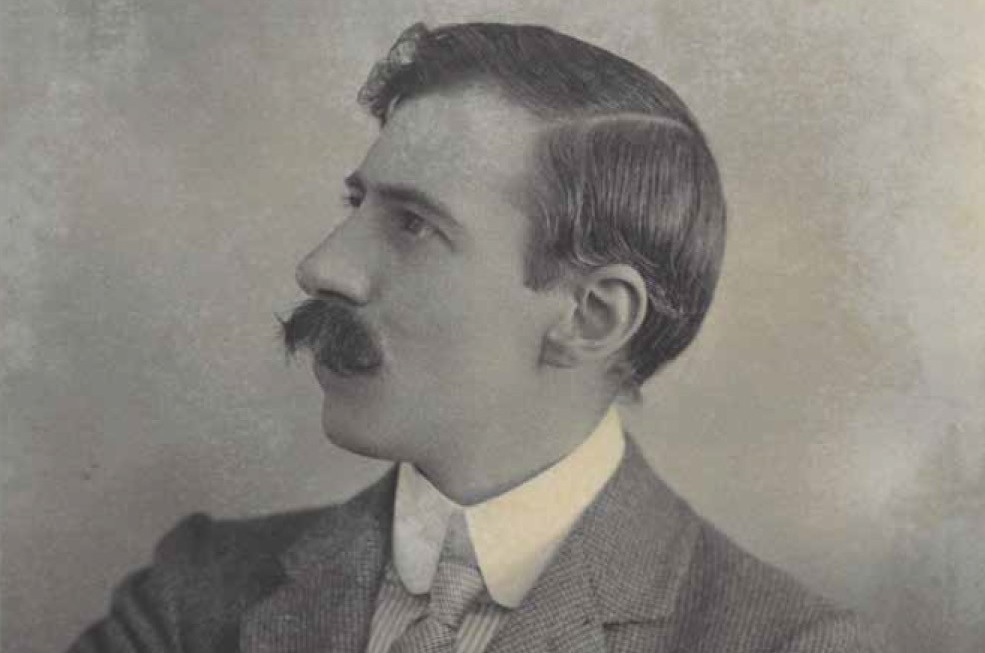

A massive book about a monumental figure in Welsh literature, this biography of T. Gwynn Jones is also a corrective, reminding us that his highly regarded and popular poetry was only a small part of his voluminous output.

Throughout an exhaustingly hard-working life, Jones generated reams and reams of newspaper journalism, as well as hundreds of short stories and a slew of novels. Indeed, Alan Llwyd suggests that if Daniel Owen is the father of the Welsh language novel then T. Gwynn Jones is its uncle. But there was more – the acres of criticism, the hymns, the essays, not to mention translations from a range of languages, all underlining the breadth and depth of Jones’ linguistic gifts.

He achieved all this despite not having much of a formal education, being denied a chance to study at Oxford because of ill health, which only serves to demonstrate the depth of his achievement when he was eventually given a chair in Welsh literature at Aberystwyth in 1919. This tale of the autodidact becoming a scholar, the bookish equivalent to the more general rags-to-riches story is all the more remarkable when one considers that Jones was wracked by illness throughout his life. He was often floored by flu in the winter and whipped himself with overwork in between times.

Punishing

T. Gwynn Jones was born in the middle of a storm and he maintained that the storm remained a part of his spirit throughout his life, being a rebel, a non-conformist, a dedicated pacifist and a staunch fighter for justice on many fronts.

His first major achievement as a poet came in 1902 when he published his second volume of verse and won the chair at the National Eisteddfod with ‘Ymadawiad Arthur,’ a long poem which allowed him to draw on his knowledge and enthusiasm for Welsh myths including Arthuriana.

It is impossible to read this biography without being astonished at Jones’ punishing work rate. He wrote no fewer than six novels between 1902 and 1906. His productivity in just one year, in 1907 matched many a writer’s output during an entire lifetime, with a steady stream of articles about literature and other subjects, three dramas, 57 poems and at least 155 short stories. Alan Llwyd suggest that in the case of the latter he was singlehandedly laying the foundations for the future of this literary form. All this took its toll.

To try to restore his health he decamped to Egypt in 1905 on a trip paid for by well-wishers. During his time there he travelled the country, saw the Pyramids and journeyed along the Nile and met a range of interesting characters, including visiting the family shop established by John Davies Bryan in Cairo at the same time that Bryan’s cousin, Samuel Evans, was head of the Egyptian Coast Guard service.

Other years saw him writing at a furious lick despite suffering from stubborn chest colds and incipient exhaustion. At the close of 1912, for instance, he was working in the National Library – where he worked as a cataloguer – by day and doing his own work at night and at weekends. It’s tiring just reading about this human conveyor belt of a writer. His book about his Middle Eastern travels had just appeared. He had just finished a memoir of his influential friend Emrys ap Iwan while his biography of the preacher, journalist and printer Thomas Gee was being typeset even as he was finishing the book itself.

He somehow also managed to find time to read his way through Greek and Latin classics, to collect Welsh folk tales, to learn Irish and a bit of Latvian and to translate plays from German, English and Greek. Not to mention producing the two-volume scholarly edition of the works of the poet Tudur Aled. Here was a man who did not rest on his laurels.

When his translation of Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Jedermann was staged at the Wrexham Eisteddfod it blew actor Sybil Thorndike away: “It was one of the most wonderful things, of not the most wonderful thing, I have ever seen in my life. I was carried away by it. It was beautiful.”

Indefatigable

T. Gwynn Jones, a Romantic poet in his early days, lived to see Romanticism dislodged by war and its shatterings. He posited the need for a new literary kind of literature, one that avoided the materialism of the times. “With regard to all forms of literature, we are probably not going to do much until we have a fresh awakening of some kind, a new interest in life, which will enable humanity once more to escape from the death-trap of mechanized materialism.”

He was his own one-man awakening, mind. He pushed literature on in many ways, pushing boundaries in strict metre poetry, turning to free verse when necessary, conjuring up some of the most terrifying ghosts in any Welsh short story and introducing naturalistic dialogue into the novel. He had artistic restlessness aplenty.

Alan Llwyd is the Welsh literary biographer par excellence – having already produced sterling works about the doomed poet Hedd Wyn and the so-called Queen of the Short Story, Kate Roberts. There is no-one better equipped to both tell the story of one of our greatest writers, and earn the right to call him Gwynn, but also to assess the work, as Llwyd is himself one of the most prolific Welsh language poets.

Here, thus, are two titans, one writing about the other but there is no clashing involved but rather great illumination as Llwyd turns the arc lamp of his scrutiny onto Jones’s astonishing oeuvre. He shows it to be a massive, massive achievement by a man who seemed to be nothing less than simply indefatigable, with boundless energy to match the fathomless wells of talent. Like Llwyd himself, one might say.

Byd Gwynn – Cofiant T.Gwynn Jones, 1871-1949 is published by Cyhoeddiadau Barddas and can be bought here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.