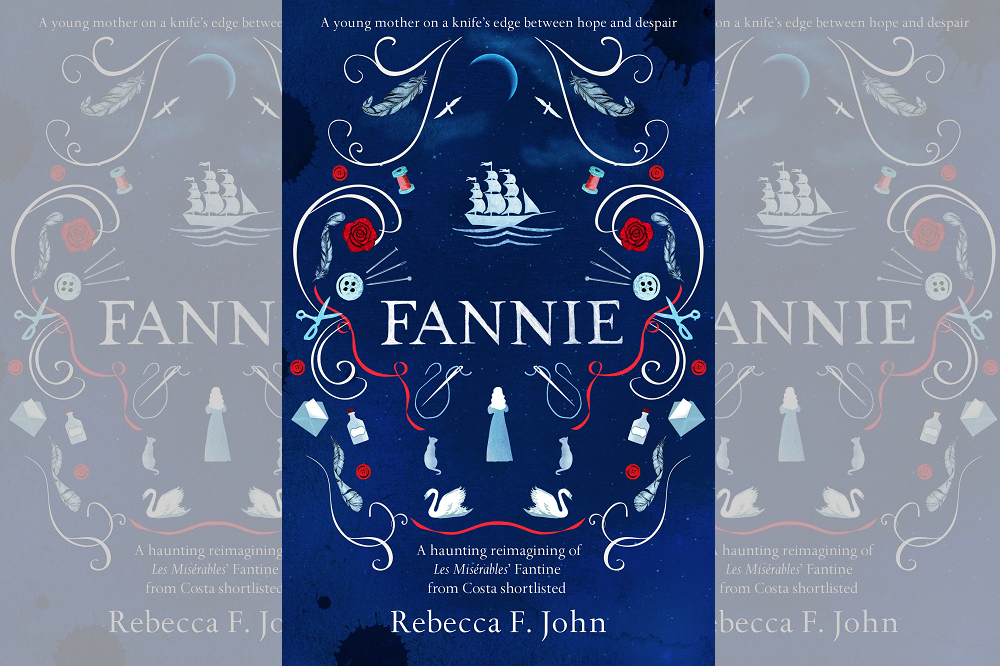

Review: Fannie by Rebecca F. John

Gemma June Howell

Taking its inspiration from downtrodden factory girl, Fantine from Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, Rebecca F. John’s Fannie is an astute feminist reworking of a damned woman archetype.

While Hugo focuses on the distinction between the hardworking and the parasitic poor, John restores Fannie’s agency as a character of endurance and survival in a masculine world of competition and greed.

Reminiscent of Jeannette Winterson’s Sexing the Cherry, which reimagines the tale of The Twelve Dancing Princesses to illustrate the subversive nature of women within an oppressive patriarchal society, John not only rejects the narrow stereotypes of women, but offers the reader an intimate insight into Fannie’s existence; revering her thoughts, dreams, and desires, which is something that is lost in subsequent adaptations of the original novel.

In this exquisitely crafted novella, John not only reframes the narrow stereotypes of women by exposing the lived experiences of prostitutes and unmarried mothers, but she also highlights the lack of these women’s prominence in historical fiction.

Within the structures of society and its predatorial pinnacles of power: the “full-bellied fox” foreman and “the moulded heads of lions and horses” staring down from rich merchants’ houses, women like Fannie were expected to “move in silence.”

But instead, Fannie secretly identifies with the “industrious young men” apprentices and seeing herself as equal, she “slinks and darts” like a cat in what John describes as an “imposing place” where “the buildings [are] as magnificent as the ships and galleons which finance them.”

Poetic deftness

Fannie opens with a poignant prologue, showcasing John’s poetic deftness while establishing the romantic, somewhat naïve mindset of the protagonist.

It is here where John introduces the conceit of power embodied in the metaphorical significance of textiles, which not only contextualises the story, but also represents a social fabric whereby Fannie’s social status is symbolically sewn into society.

“The fabric is a light cotton… but not heavy enough to resist the wind which paws at it through the open window,” foreshadowing an inner strength and resilience.

This metaphor extends to “a billowing sail, blinding her to everything which lies ahead;” the unseen obstacles embodied in the ship’s sails… of overseas commerce and the darker trades which accompany it.

In chapter one, ‘Abandonment,’ the sailors disembark as a line of prostitutes are “parading down the jetty like a chorus of showgirls,” who have “rouged over their sickness” and have covered their bald patches with ostrich feathers, yet John places the women on an equal footing with the sailors, who had “to begin shifts of their own,” thereby legitimising and elevating their profession.

And, despite their lower status, Fannie is not judgemental as “She knows too well what cruelty men are capable of.”

Fannie may be illiterate, but she is fully aware of the insidious nature of a sexist society, where the anonymised “blackened shapes of men,” agents of patriarchy like the “creeping damp” in her bedsit, ever-present on the factory walls, growing and thriving unnoticed, unchecked.

Commodities

But despite the constant reminder of Fannie’s weaker status, John portrays her as “both small and gloriously bright,” emphasising how women like Fannie may be small, but have hidden capabilities.

In chapter two, Needlework, Fannie is abandoned again, but this time by the mayor who is also the factory owner and “is too busy to notice that the foreman takes pleasure in their discomfort. The promise of its easing is a commodity he attempts to trade – for ‘the right price,’ he suggests, leering.”

A predicament not dissimilar to the women who work on the docks (also commodities), Fannie begins to make her own stitches in life, and taking the first steps towards autonomy she moves out of the “silence,” to draw on her inner fortitude where she can begin to take ownership of her and her daughter’s destiny.

Whilst highlighting the multiple layers of oppression, Fannie is ultimately an evocation of the hidden injustices experienced by women from lower social backgrounds past and present. Following in the traditions of revisionist feminist writers, Jeanette Winterson, Carol Ann Duffy and Margaret Atwood, Fannie has historiographical significance.

It is a notable contribution to the feminist struggle to escape the power structures of a male dominated society.

The book’s epigraph: “To all women who have been silenced,” not only speaks of women living in 19th Century France, but also resonates with women in the same position today.

In this sense, the story of Fannie transcends borders and time as it tells a universal tale of working-class women’s fortitude within an enduring matrix of female domination.

Fannie is published by Honno Press and is available to purchase here or from all good bookshops

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.