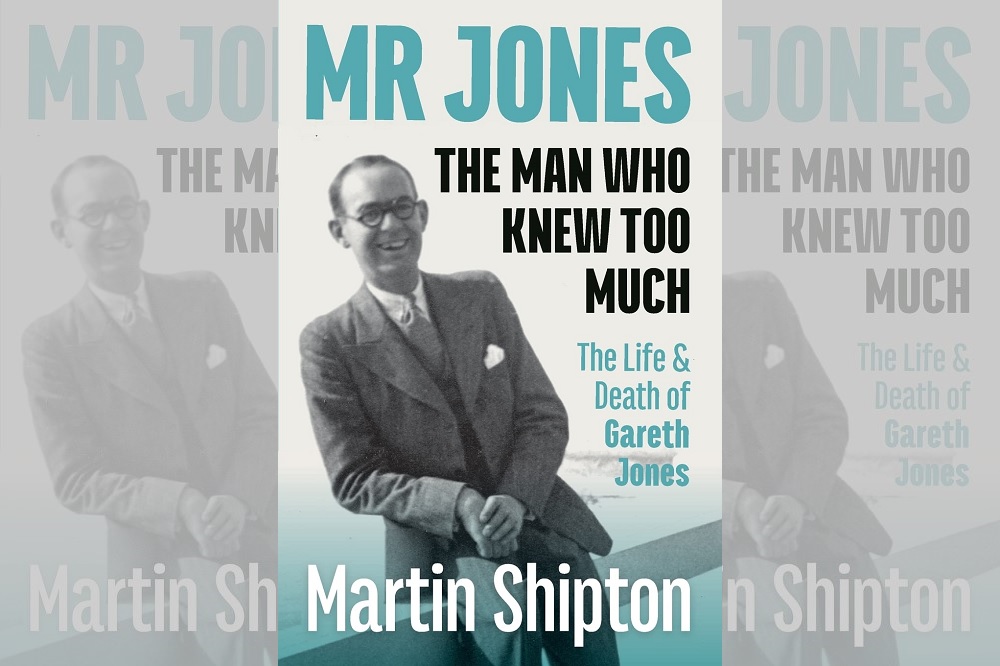

Review: Mr Jones – The Man Who Knew Too Much – The Life & Death of Gareth Jones by Martin Shipton

Jon Gower

Jon Gower

Before he was mysteriously murdered in Mongolia on the eve of his 30th birthday the Welsh investigative journalist Gareth Jones had lived a concertina of extraordinary life, squeezing in experiences and explorations that reflected great personal energy and deep intelligence, coupled with a communicable joie de vivre.

He worked for former Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, met the likes of US President Herbert Hoover and hyper-influential newspaper magnates Lord Beaverbrook and William Randolph Hearst.

This exceptionally bright young man – able to speak five languages and blessed with a rare ability to analyse foreign affairs in depth – was also an alert-eyed witness to some of the 20th century’s shaping events, from the vicissitudes of the Depression in New York through the tightening of Mussolini’s grip on Italy to the rise and rise of the Nazis in Germany.

It was a Germany besotted with both aeroplanes and power at the time and Jones was afforded a rare opportunity to see both in very close proximity when he became the first foreign observer to fly with the country’s new chancellor.

Even the young and relatively inexperienced reporter could sense the import of the moment:

If this aeroplane should crash then the whole history of Europe would be changed. For a few feet away sits Adolf Hitler, Chancellor of Germany and leader of the most volcanic nationalist awakening which the world has seen…The occupants of the plane are, indeed, a mass of human dynamite…

Compelling life

It is entirely fitting that a fellow Western Mail journalist, the paper’s current Political Editor- at-Large Martin Shipton should be Jones’ latest biographer as they both share the gift of being able to see the big picture as well as finding the telling detail.

Shipton spent three years assembling this engaging and compelling life, poring over the extensive archive of missives in the National Library in Aberystwyth – Jones was nothing if not an inveterate letter writer – reading his published articles and turning the pages of his crammed notebooks.

The portrait that emerges is of an ‘intellectually inquisitive livewire’ who had enormous reservoirs of charm and an abundant zest for life coupled with a keen and permanently engaged curiosity about how things worked, especially those of global geo-politics.

Being a fluent Russian speaker, all roads perhaps inevitably led to Moscow, where Jones met foreign correpondents such as the Manchester Guardian’s Malcolm Muggeridge.

But before that he had to master the language, which involved hitching a lift on a coal boat leaving the docks of his home town in Barry to travel to Bergen in Norway, then on by train to join another vessel bound for Riga where he polished his language skills.

Speaking the language was key to understanding what was going on in the Soviet Union. There he had access to diplomats and fellow journalists but when it came to exploring food shortages and famine conditions in Ukraine he was pretty much all alone.

Evidence of suffering

The Soviet Union officially denied there was such a gnawing hunger but Jones, breaking the ban that forbade foreign journalist from venturing much beyond the city limits of Moscow, met peasants who had walked there to buy or beg for bread, while others paid for loaves with gold, an immoral exchange rate if ever there was.

He also stayed with peasants whose children’s bellies were distended by hunger, filled his notebooks with evidence of suffering such as the man he saw who fished out a piece of bread from a spittoon and ate it.

Bread was desperately sought after but seed, too, was in scarce supply and livestock numbers were perilously depleted.

Unemployment, too, was a scourge, as the attempt to stimulate an industrialized society and to create huge collective farms faltered – meanwhile throwing small farmers off the land they had previously worked successfully and leaving factory workers denied the bread tokens that came with the job.

Having see the famine with his own eyes, Jones had an enormous scoop on his hands but yet he decided to disseminate the story by holding a press conference in Berlin, sharing his story with other journalists in a way that could seem overly generous, or possibly naive.

He himself had only notched up a month’s experience of working on the Times and was yet to start work on the Western Mail.

Whatever the reason behind the press conference the huge story claimed space on front pages, catapulting Jones to the status of a celebrity scribe into the bargain.

Dissident voices

The Soviet authorities took a dim view of this all, of course, but they were not the only dissident voices.

One who refuted Jones’ depiction of the situation in Ukraine was the socialist playwright George Bernard Shaw.

He, along with 20 other writers who had recently visited the Soviet Union were signatories to a letter that described a hopeful and enthusiastic working class and took the opposite view to the ‘present lie campaign’ which they thought was damaging the reputation of the USSR.

Shaw even met Stalin, a despot who would send millions to their deaths in the gulags of Siberia and elsewhere, expecting to ‘see a Russian worker and I found a Georgian gentleman.’

He rubbished the notion of Soviet hunger by praising a Russian meal, being ‘the most slashing dinner in my life.’

And other journalists piled in, such as the New York Times’ Moscow bureau chief Walter Duranty who poured scorn on Jones’ claims that peasants were starving and dying in great numbers.

Taken captive

Gareth Jones was on a round-the-world trip when he met his sudden end.

As he encircled the globe he met the great architect Frank Lloyd Wright as well as the Welsh settlers of Wisconsin, pausing to hold audiences spellbound in public lectures along the way. He visited Pearl Harbour in Hawaii before embarking on a gruelling trip into Inner Mongolia and the Japanese occupied area of northern China.

He was taken captive along the way, although famously Jones entertained his bandit kidnappers by singing Welsh songs and hymns including spirited renditions of ‘Dafydd y Garreg Wen’ which had them calling for encores.

Shipton unpeels the layers of rumour and counter-rumour that sheath the truth of what actually happened to Jones, revealing connections between the car in which he travelled and Soviet intelligence.

Why he was killed will forever be a mystery as will the identity of the person who pulled the trigger.

Truth to power

One of Martin Shipton’s declared aims in writing this book is to elevate Gareth Jones’ status to that of an authentic Welsh hero.

At a time when bleatings about false news go hand-in-hand with Trumpian attacks on truth itself, a journalist such as Jones who spoke truth to power deserves such elevation.

His was a sterling example of intrepid journalism battling falsehoods, in his case nothing less than skewed Soviet accounts of a famine known by Ukrainians as the Holodomor, driven in part by Stalin’s own policies and which easily invokes the word ‘genocide.’

As you’d expect, Shipton allows Jones’ own words to carry the narrative along, the story of a life well lived and one cut tragically short by the impact of three bullets in wild bandit country.

It’s a remarkable biography, superbly well researched and deftly told.

Hero? Well, yes, indubitably so going by this account although one gets the sense that it’s a word Jones would have abjured: there seemed to be very little arrogance or haughtiness about him.

What strikes the reader much, much more is how he seemed to be such good company – articulate, enthusiastic and abidingly curious – which makes his very premature death all the more saddening, as he had so much left to do.

Mr Jones – The Man Who Knew Too Much is published by the Welsh Academic Press and can be bought here or from good bookshops

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

I will have to see if ‘Gwynedd Library’ can afford a copy…a timely work!

He can’t be the Mr Jones Dylan was singing about then…