Review: Nick Drake – the Life by by Richard Morton Jack.

Welsh singer-songwriter Ayres considers the work and times of a tortured soul.

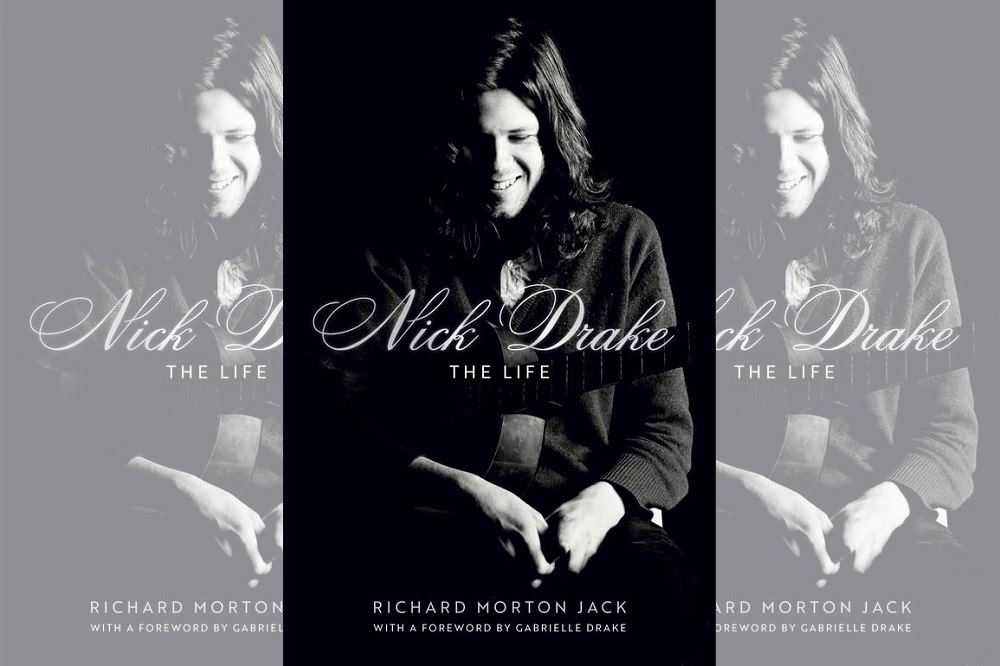

Superficially at least, Nick Drake seemed to have it all. Devilishly handsome in a dark, brooding, Byronesque manner he cast a spell over his fellow undergraduates at Cambridge — both male and female— and, as if this wasn’t enough, he was also something of a wizard on the guitar.

In fact, having made it to Cambridge by the skin of his teeth (and the fact that at Marlborough, he’d held the record for the hundred metre dash for quite a few years) the guitar was just about the only thing he was interested in.

Strumming a guitar was, of course, more or less obligatory in the age of Woodstock and Aquarius but what separated Drake from the crowd was his dazzling skill and dexterity. “I’d never met anybody of my age who could do anything that well,” says one contemporary at Cambridge.

“He just magically got those sounds out, those strong fingers flying across the fretboard.”

Fate seemed to smile on the golden boy when, as his enthusiasm for studying English literature faded (not that there had been much of a spark there in the first place!), he landed himself a record contract with Island Records.

Leaving Cambridge behind to follow his dream he recorded his debut album Five Leaves Left.

Haunting, mellow, delicate and beautiful it had the aura of an immediate hit— especially in an era where singer songwriters such as Elton John and Cat Stevens were just emerging and where Drake’s label mates Fairport Convention were creating such a stir.

Upon completion, “everybody,” according to the album’s engineer John Wood, “thought it would be a storming success.”

Harsh reality

But it wasn’t. And no one was more puzzled by its lack of commercial success than Drake himself. But, as Richard Morton Jack painstakingly points out, the tragedy was clearly not so much a lack of talent on Nick’s part as a complete naivety in the face of the harsh reality of the music business.

Even back in the indulgent early seventies where “nurturing” labels like Island were famously sanguine about the lack of immediate commercial success, they expected at least a modicum of promotional co-operation from their roster.

This might include embracing tours, TV, radio sessions and interviews with the burgeoning UK music press. Drake, unfortunately, did not grasp the importance of any of these.

As his friend Paul Wheeler points out that, for Nick, ‘…the actual musical side of being a gigging musician was quite limited…he didn’t like the surrounding business— the trains, the meeting strangers, the bed and breakfasts, the hustling.” And to be fair, perhaps some of the engagements he was booked on did him no favours at all.

One brutal and almost surreally ill-advised tour supporting the up and coming Genesis on a string of dates in northern working men’s clubs ended with the band having to perform The Hokey Cokey to keep the audience onside.

Horrendous as that must have been for Gabriel and crew, I, for one, will happily admit that I’d pay a small fortune for a bootleg!

Commercial flop

As an upper middle class boy who’d had a privileged upbringing the overwhelming impression one gets is that Drake half expected the world to come to him on his own terms.

A seemingly incongruous interview with teenybop mag Jackie becomes reduced to monosyllables. He is invited onto The Old Grey Whistle Test but doesn’t bother to turn up.

As a result, his follow-up album Bryter Layter (widely expected to be the ‘breakthrough’) is another commercial flop and this heralds a spiral of depression and mental health problems from which Nick Drake never recovered.

Visceral tragedy

Had he lived he would have been bemused and possibly even pleased with the respect his work is held in these days. I personally got hooked after reading a brief biography in the NME Book of Rock and, intrigued and flush with birthday cash, I bought the re-issued box set of his complete recorded work Fruit Tree in 1979.

From then on I became something of a Drake evangelist— turning my university friends (and anyone who’d listen) on to him. Reading this immensely detailed and thoroughly engaging biography is something of a mixed joy for a fan like me because what it chronicles in the final third of the book is the visceral and painful tragedy of a talented young man’s slide into depression and drug abuse ending, almost inevitably perhaps, in a verdict of suicide.

All this despite the support of his wonderful family and his indulgent record company. I knew the story of course. But it’s told here in such a stark and unflinching manner that it’s a bit like being hooked by a dark, sad and tortuous thriller.

Uncool

Singer songwriters quickly became uncool as the seventies unfolded and as pub rock morphed into punk. Their esoteric concerns and open-tuned indulgencies seemed increasingly irrelevant to a restless youth eager for a shot of energy and buzz.

Despite this however, as the influential journalist Nick Kent points out in the epilogue of this book, interest in Nick Drake ‘snowballed quite quickly after his death.’ It’s one of the immutable truths of rock and roll that the only thing that sells more records than a rock star is a dead rock star— especially if he or she also happened to be incredibly good-looking.

But there was more to it than that. As Kent goes on to say— “1976 was the time of punk, when everyone hated sensitive singer-songwriters like James Taylor and Joni Mitchell, but for some reason that crowd did like Nick. I remember Joe Strummer, the Damned and Paul Weller all liking him in those days and it wasn’t because he’d died young— it was because his music spoke to them.”

One of his friends comments that, in terms of pop music, Nick ‘thought he could latch on to that world without going through the slog.” In the end, of course, Nick Drake was proved right.

The music world did eventually come to him. He didn’t have to go on tour or TV or talk to journalists or, indeed, to even raise a finger. But the price he paid for that belated acclaim was enormous.

Nick Drake— The Life is published by John Murray and is available from all good bookshops.

Euron “Ayres” Griffith’s latest novel The Confession of Hilary Durwood is published by Seren, while his ‘semi-musical’ memoir ‘Six T-Shirts- A Casual Life’ is due in early 2024.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

The regularity with which newspapers run pieces about Nick Drake is no surprise.

The man was one of the best singer songwriters we ever had, albeit no for long enough.

Euron Griffiths trying hard to convince us all that ha is English.

Four novels in Welsh. One item about Nick Drake in English. Who knew my “Welshness” was so fragile Arthur?

OK,digon teg ond pam yr ‘Ayres’?

Dyna ydi’r enw dwi’n ddefnyddio pan yn sgwennu a chynhyrchu caneuon. Mae o yn mynd yn ol i’r wythdegau hwyr pan oeddwn mewn band o’r enw The Third Uncles ac mae rheini sy’n tueddu i dilyn fy stwff (dim lot dwi’n cyfadda!) yn fy adnabod dan y ffug enw yma. Gan fod hon yn erthygl sy’n ymwneud a miwsig oedd hi yn gneud sens I gyfeirio at yr enw yma rwsut. Gobeithio fod hyn yn egluro.