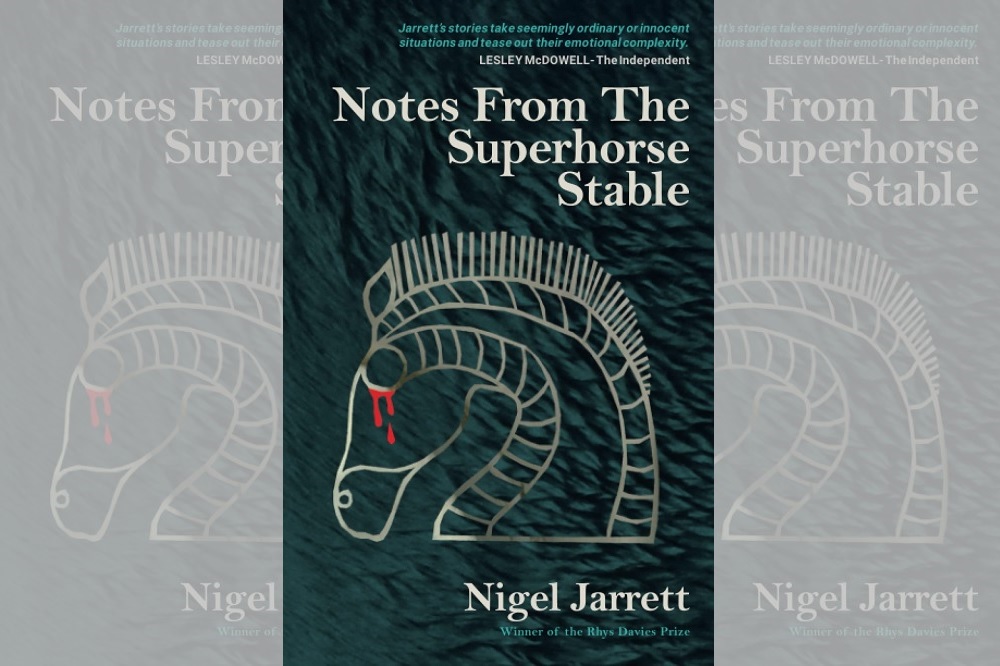

Review: Notes From the Superhorse Stable by Nigel Jarrett

Hammad Rind

As you open award-winning Welsh writer Nigel Jarrett’s latest novel Notes From the Superhorse Stable, you are encompassed by an overwhelming feeling that you are setting off on an unusual journey, something similar to the one protagonist and principal narrator Francis Taylor undertakes during a career break:

“Some ‘resting’ actors write books; some make snow globes; others train their memories. I joined the Ancestry website.”

We learn that Francis, an actor, is writing these Notes during a forced “rest” caused by the vicious bite of an angry sow on the set of the actor’s latest TV appearance.

The break also offers Francis the opportunity to dig up a long-lost relative, Harold, a former coal-miner and artist, who is spending his retirement years in a village in West Sussex.

Masked head

Along the way, and through many detours, we are introduced to a varied cast.

The actor’s “come-and-go” partner Julie is a writer, whom Francis first meets during what might have been his finest performance as the masked head of the horse in Peter Schaffer’s Equus alluded in the title.

Julie unwittingly also assumes the occasional role of the secondary narrator of the book thrust on her by Francis, as he adds her “missives to herself” to his Notes, having accessed them from a stolen laptop.

Francis’s other part-time lover is Mona Strange, another struggling though complacent actor and a long-suffering but devoted daughter, with a fondness for ‘viral’ videos and amusing gifs, who rather strangely never moans about her fate.

And then there is Ethel Chrimes, Harold’s clairvoyant companion and one of the leading members of a reading club, which, as we at length find out, is much more than just a group of country book-lovers.

Creatures

From the very start, however, we realise that these humans are not the only characters playing the roles assigned to them in the book.

From the horses alluded to in the title through the observation by Nietzsche that cattle are unaware of the passing time to the disturbing news about a colony of Caribbean ants in a Gloucestershire tourist attraction, the book is crammed with all kinds of creatures.

Primates, birds, rodents and insects appear on almost every page of the book.

An emotionally repressed middle-class man teaches his pet parrot swearwords for his own amusement. A multi-prizewinning horse mysteriously vanishes from the pages of history. A resident of an ‘eldercare outpost’ with a Zero Pet policy surreptitiously smuggles in a mate for his two female hamsters just before his departure.

“An insect, gorged on the luxuries of summer” and “eager to flee the captivity enforced by newly-closed windows” perishes soon after leaving his confinement.

In a way, this modern ‘bestiary’ mirrors the natural world we share with animals as just another specie, but which, in our obsession to possess and mark everything as ours, we have selfishly taken as solely our playground.

Under the delusions of being their masters, the “Beastly Humankind” treats these other actors living besides them cheek-by-jowl in all kinds of brutish ways through both their actions and words.

And when they are not actively or neglectfully using, abusing or harming them, humans assume a condescendingly benign attitude towards these creatures.

Loneliness

Almost in a sharp contrast to this seemingly claustrophobic cohabitation is the theme of the eternal loneliness of the modern human pervasive throughout the novel.

We come to this world alone and have to leave it on our own too, and during these two most important events in our lives, loneliness accompanies us, often despite the illusions of being surrounded by a family, friends and lovers.

This ever-present solitariness at times has negative effects on people, leading them to serious health issues, especially depression, called the ‘black dog’ by Winston Churchill, an apt appellation, as Francis reflects:

“the description of something in the room impossible to ignore or get rid of, like a slavering Labrador in the corner, always wanting and waiting to be taken out for a walk, and if you weren’t the animal’s owner or found black Labradors slightly menacing, a dog that could ‘turn’, as the saying goes; a dog, in other words, exerting total control.”

Inspiration

With its opening chapter aptly titled “On Digression,” the book is full of digressive jottings: factual tidbits, news clippings, anecdotes of personal and historic nature, blogposts, encyclopaedia entries and musings on a number of subjects.

In the words of Francis, it is “more a rattle-bag of scribble” than a conventional story, “though”, he reassuringly adds, “there’s a story in it”.

In many ways, it reminds one of the meandering themes of similar works alluded to in the book: Richard Burton’s seventeenth century The Anatomy of Melancholy and James Joyce’s modernist masterpiece Ulysses, especially the famous concluding monologue by Molly Bloom, seemingly the inspiration for Julie’s jottings with their partiality for Joycean wordplay and disdain for punctuation.

In his Acknowledgments, Nigel Jarrett has also referred to Notes as “not a novel in the traditional sense but a story told in a different way”.

Stylistically refreshing and with a conscious attempt to be doing something different, the book rightfully claims a unique space among currently published fiction.

Notes From the Superhorse Stable by Nigel Jarrett is published by Saron Publishers and is available here and from good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.