Review: Rhys Davies: A Writer’s Life is a lively account of one of Wales’ most important literary figures

Matthew G. Rees

Story-writer and novelist Rhys Davies was at the forefront of the remarkable wave of Welsh writing in English that had its roots in a geographically small area of industrial South Wales – notably the Rhondda Valley and its environs – in the last century.

Fellow writers in this rich flowering included Lewis, Jack and Glyn Jones, Ron Berry, Gwyn Thomas, Alun Lewis and George Ewart Evans, to name but some.

Davies (1901-1978), from a shop-keeping family in Blaenclydach, near Tonypandy, lived most of his life outside Wales. One of his returns, in the 1920s, sparked (according to his account) a flurry of interest: newspaper reporters seeking interviews, and a request ‘oilily’ made by a churchman to donate a signed copy of one of his novels to a special ‘Royal Stall’ at a local bazaar.

And yet the place of Davies in the Welsh pantheon is an awkward one, not least for his habit of issuing difficult, indeed at times reproachful, commentaries on the land of his birth and its people.

While his fiction never matched the full-bore caustic blast of Caradoc Evans’ notorious My People, the bitter-sweet nature of Davies’ relationship with Wales – at times it seems to have been a deal more bitter than sweet – was much more pronounced than Dylan Thomas’ casually dismissive ‘The land of my fathers. My fathers can have it.’

Graham Greene famously commented that those who write must have a splinter of ice in their hearts. Davies, it seems, fair rattled with them.

He was nothing if not a contrarian: in his youth, a quitter of school and chapel, a dandy who wore spats and carried a cane, an eater of cake amid industrial strife (thanks to his parents’ grocery store) and, in adulthood, a gay man emerging from the macho backcloth of coal country.

Enigma

Central to his phenomenon has been the secrecy with which he guarded his life, particularly – having left Wales – in London: shifting from one address to another, living out of a single trunk. In part, this was necessary for the avoidance of arrest in an age when homosexuality was illegal. Yet – throughout his life – Davies seems to have gone further, active in the cause of his subsequent enigma – setting dubious trails, asserting inconsistent ‘facts’, writing a demonstrably unreliable memoir, creating his own myth.

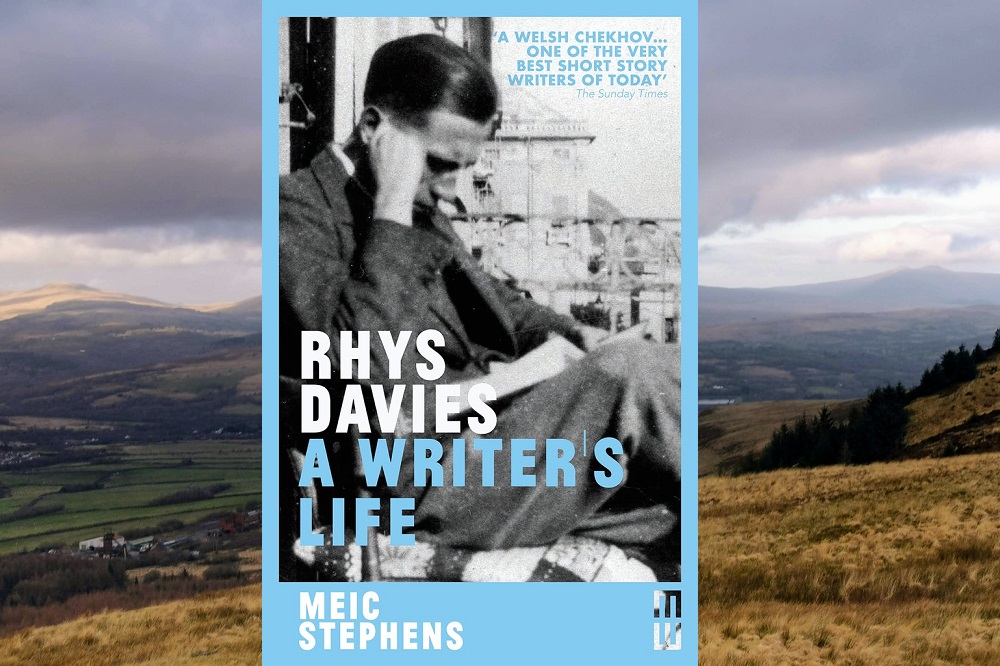

Rhys Davies A Writer’s Life (the title is underwhelming, though perhaps chosen deliberately as a way of cutting through the ‘dissembling and evasion’ of its subject) is a book that sets out to cast light on and, if possible, demystify the life of the man who wrote twenty novels and more than a hundred short stories, not to mention plays, novellas and topographical accounts of Wales.

The late Meic Stephens, a professor of Welsh Writing in English at the University of Glamorgan, is unambiguous about Davies’ literary status, declaring with his opening sentence: ‘Rhys Davies was among the most dedicated, prolific and accomplished Welsh prose writers in English.’

Although far from disregarding Davies’ writing (his works are discussed and investigated in an informative way throughout), Stephens’ sights in this book are on the mind and figure of Davies, with the aim – if it can be done – of separating man from myth and discovering the real Rhys Davies.

Two matters were critical in setting the course of Davies’ life, Stephens makes clear. Firstly, his upbringing in the ‘shopocracy’ – that class of socially and financially elevated commercial trader to which his family belonged by virtue of their ownership of a grocery store; secondly, Davies’ homosexuality – which Davies seems only to have been able to fully liberate by leaving Wales for London.

Having – to the consternation of his parents – quit grammar school in Porth, Davies – a bookish, aloof-sounding, Chekhov-admiring teen, whose reading also included the Wilde-led Edwardian ‘Decadents’ – worked for a while in their store. Possessed of a notably steely will, according to his biographer, he then took himself off to London with vague hopes of becoming a writer.

Promiscuous

A major asset to Stephens’ book are contributions from Davies’ younger brother Lewis, who suggests that Davies’ move to the metropolis – where he obtained jobs in drapery and men’s outfitting – enabled him to lead life in the way he wanted to, which, in his early years at least, involved a high degree of promiscuity. ‘He was known to other men as Rhoda,’ notes Stephens, ‘an alias near enough to the name of the Valley about which he wrote so prolifically. If he was promiscuous, as his brother claimed, the names of his partners have not been recorded, because none lasted beyond the one-night stands and furtive encounters that were his preferred options.’ In London, therefore, much of the mystique that Davies was to draw about him throughout his life, begins.

Stephens strives admirably to guide us through these years, with many notes and references to texts. Yet the absence of testimony from a partner is – inevitably – rather telling.

Secretive

The same is true when it comes to Davies’ relationship with Anna Kavan, also known as the novelist Helen Ferguson, a heroin addict who for a period had been a psychiatric patient. Here, Stephens – honestly – concedes: ‘The precise nature of the curious bond on which the unusual relationship between Davies and Kavan was based, and which lasted until her death in 1968, is now lost. Seeing each other so frequently and privately, they exchanged only the most perfunctory of letters, and sometimes postcards, and so there is very little correspondence that might otherwise have shared light on what they felt for each other. They were also secretive,’ continues Stephens. ‘Davies, no stranger to editing his own life… understood, quite instinctively, her need to evade the truth and hide it from others.’

After Kavan, Davies’ great love, Stephens notes, was a trainee military trumpeter named Colyn Davies, who’d suffered a nervous breakdown and had been invalided out of the Navy. He was the subject of Rhys Davies’ well-known story ‘Boy With a Trumpet’. Colyn Davies – ‘entirely heterosexual’ – had no interest in a physical relationship with the writer, and in time their closeness petered. ‘This must have been a severe blow to the writer,’ comments Stephens, ‘but he left no recorded remark as to the hurt it caused him.’

Stephens provides an interesting account of Davies’ time in the south of France, which included a stay with D.H. Lawrence and his wife Frieda – Davies’ involvement seemingly stemming from a determination by Lawrence to have a mass edition of his novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover published in England, with Davies apparently contemplated as the conduit for his manuscript.

Saucy

Here, we get a sense of the mixture in Davies’ personality of the saucy and the strait-laced. Soon after meeting the Lawrences, the Welshman recounts a risqué story, which does not go down well with his hosts. Later, at a restaurant, Davies glances around at other diners – a little uncertainly, it seems – as Lawrence, more than once, uses the F word.

A coda to their time together comes later in life, when, annoyed at the theorising – popular for a period – that Lawrence might have been homosexual, Davies insisted that this was not the case, disclosing that he had once shared a bed with Lawrence in a Paris hotel, when absolutely nothing (of a sexual kind) had occurred.

There was a rather brittle side to Davies’ persona, it seems. He was, it appears, a man of relatively few lifelong friends. H.E. Bates was among those with whom he fell out – perhaps understandably – after Bates delivered a damning review of one of his books. Davies commented: ‘Master Bates has had his opportunity at last. It’s nice to have his tribute… He ought to be turned over and have his mean little bottom smacked.’

There also seems to have been jealousy and (at times breath-taking) self-importance. In a dismissive account of Jack Jones’ best-selling novel Rhondda Roundabout, Davies – much of whose writing was confined to small ‘runs’ – wrote: ‘Jones seems not to have the slightest amount of imagination to aid him. I’m disappointed. It would be nice to have a fellow writer to sit beside me. I feel lonely about Wales sometimes!’ A kinder episode saw Davies donate £3 to a fund opened to bring back to Wales the body of Dylan Thomas after the poet’s death in America.

Stormtrooper

Davies, it seems, fibbed about his date of birth to confuse the authorities regarding possible conscription during World War Two – one of his old pick-ups, incidentally, going on to become a Nazi Stormtrooper. Davies wrote in a letter: ‘I suppose by rights I ought to be in khaki, but I hate it as a colour.’ He was also, Stephens notes, given to ‘Proustian’ hypochondria.

Davies’ political inclinations, in so far as he seems to have had any (his father was a Liberal Club member), seem to have been rather removed from those of the majority in ‘red Rhondda’, as it was dubbed. He was part of the circle of writers centred on the London bookshop of the socialist Karl ‘Charlie’ Lahr and is said to have prayed for a Labour election victory. He contributed to the Left magazine Tribune – ‘humorous, non-political sketches’, Stephens notes. Davies was scornful of what he perceived as the self-serving elitism of collier’s son Lawrence, who he felt favoured ‘a community of choice spirits living in some untarnished place (with, of course, himself as ordained leader)’, where the world’s welfare might be held at heart ‘from a safe distance’.

He was also ‘unsympathetic’ to Welsh nationalism as a political force, according to Stephens, and found a suggestion by Saunders Lewis that the mining valleys should be deindustrialised, with their people returning to work on the land, ‘as preposterous as it was offensive’. Prone to romantic fantasising about his own Welshness, according to critics, Davies had next to no interest in the Welsh language (which his parents seemingly spoke only when addressing one another in the family home on something they didn’t want their children to hear).

Fellow Welsh writer Glyn Jones criticised Davies for what Jones felt was the other’s lack of ‘philosophy’ (by which he meant political ideology, according to Stephens). Davies answered in an interview in 1954: ‘I become uneasy when a novelist begins to expound, preach or underline, state a case, even briefly, or when he douses his characters with over-personal wealth of vision. This sort of philosophising must be kept, with me, incidental.’

However, another Welsh writer, George Ewart Evans, from Abercynon, whose parents were, like Davies’ in the grocery trade, was flabbergasted by some of Davies’ positions and called Davies’ account of the Rhondda, My Wales, a book of ‘fascist-fodder’ and ‘startling theories’.

Sympathy

In an interview with the Western Mail, Davies responded to his critics in a very Davies-like manner: ‘I have been brought to task for my apparent ‘cruelty’ to the working classes, but that is the last thing I would wish to be, for my sympathy with the Welsh proletariat is very real and very deep. I do feel, however, that there are in Welsh phases of life and types of humanity so raw and crude that if one writes of them with sincerity, one might easily appear cruel.’

In Stephens’ eyes, Davies was ‘distinctly petit bourgeois’ in attitude, ‘unlike most of his Welsh literary contemporaries, writers like Jack Jones, Gwyn Thomas and Lewis Jones (another Blaenclydach boy), who were variously but staunchly proletarian in upbringing, sympathies and lifestyle’.

The matter of whether Davies demeaned his countrymen and women – and whether he did so deliberately – hangs over much of this volume. Stephens marshals the criticism of Davies and Davies’ defences in a way that seems fair. Yet one wonders – when it comes to Davies’ fiction – whether this criticism isn’t founded on a misunderstanding of part of the point of fiction and particularly the kind of fiction that Davies was given to writing.

Unsettling

When it came to short stories, Davies was often a practitioner of the unsettling, the Gothic and the darkly humorous tale. His receipt of an Edgar Allan Poe award in 1967 for his story ‘The Chosen One’ is an arrow to his market. In terms of what he wrote about, ‘the eccentric’ was his frequent go-to, as Stephens points out. Hence we have a drunken widower falling into his wife’s grave at a funeral (in the story ‘A Human Condition’) and, elsewhere, in ‘The Resurrection’, a woman rising – inconveniently – from her coffin, where her body has been laid out prior to burial, to ask for a glass of water. (She is coaxed to lie back down by her avaricious sisters.)

Albeit employing (perhaps) recognisable backcloths, these are – of course – fantastical, cartoon-like creations. Similarly, the creepy Femm family and their mute manservant Morgan, as conjured by the pen of J.B. Priestley, aren’t – one hopes – true to Wales. But they live and breathe in the pages of his Wales-set Gothic horror novel Benighted. At other times, Davies’ stories have a fairy-tale quality.

One detects the influence of such figures as Dr William Price, of Llantrisant, who Stephens describes as Davies’ ‘great hero’: ‘quack, druid, Chartist rebel, exponent of free love, nudism and moon-worship, and pioneer of cremation…’ Also, possibly, the lingering call of the habit Davies had as a boy of visiting – voyeuristically – houses where coffined corpses were on display, in order – with another local lad – to ‘pay their respects’ (to people they knew nothing of).

Marketable

Davies clearly saw many of his stories as entertainment. A virtue of the short story, he said, was that it could be ‘allowed to laugh’. People will have their own views on whether his jokes were at the expense of the dignity of his countrymen and women. Stephens suggests Davies was responding to what the London publishing scene wanted. ‘Life in Wales seemed to the metropolis, in the long afterburn of Caradoc Evans and the runaway success of How Green Was My Valley, to be full of local colour – venal peasantry, rustic sex, radical politics and lyrical miners – that was eminently marketable in England.’

It’s certainly possible to understand how Davies’ heavy dependence on portrayals of his countrymen and women – and in a way that at times cast them as naïve – has been irksome to some, particularly given his own, removed life in London. His writing was in many ways of a piece with Chekhov and Maupassant, slightly before him. Certain stories seem interchangeable between the trio. The difference (and perhaps for some it is the sticking point) is that Davies’ work was for an audience whose larger part was outside his home country – and in England, at that.

That Davies wrote well, particularly when it came to short stories, seems not to be an issue. Glyn Jones and Graham Greene praised his ability. John Betjeman, commenting on Davies’ Collected Stories, said: ‘Rhys Davies is a first-class writer and every short story in this book is a novel in itself.’ And Stephens states: ‘… there is a remarkable consistency of quality in Rhys Davies’ mature work that puts it in the first rank of twentieth century short fiction.’

How this ability and style came about isn’t really answered. Maybe it can’t be. Having left school at sixteen with no qualifications, Davies seems to have been a marvel of self-education.

Distance

Part of the answer to his peculiar ability may lie in the distance that was both imposed on him (by his upbringing and his sexuality) and that which he imposed on himself (his separation from others and a seeming determination to remain detached), thereby enabling him to exercise what Stephens calls his ‘camera-like eye’ and get on with the mental sifting and sieving of what he had seen, its melding with other experiences and knowledge, and their eventual strange, alchemic conversion into fiction. Although unable to type, Davies was immensely committed to his craft and a disciplined writer.

Few authors have whole bodies of work that stand the test of time. Some of Davies’ writing has long passed into the category of ‘museum piece’. But plenty is still impressive and powerful. ‘The Nightgown’ (a woman effectively enslaved by the boorish men of her family buys – in instalments – the fine gown that will be her death shroud) and ‘I Will Keep Her Company’ (an elderly man perishes in a snowbound cottage where his wife already lies dead, before a hectoring nurse can intervene) are but two superior stories that come to mind.

As well as telling Davies’ life-story, Meic Stephens has constructed an engaging social history. The events of Davies’ life are interleaved with those of the Rhondda, where in 1923 some 252, 617 men hewed 54.25 million tons of coal, the peak of production. The story is leavened with interesting – sometimes amusing – asides. We learn, for instance, that during the Tonypandy Riots – when sixty shops were attacked in an apparent sign of the miners’ disapproval of the links between the shopocracy and the coal-owners – the chemist’s shop of Willie Llewellyn was spared. Llewellyn, a former rugby player, had been prominent in Wales’ legendary victory over the hitherto invincible All Blacks in Cardiff in 1905.

Anxiety

Although not without funds, Davies – seemingly careful with money throughout his life, save for some concern over the smartness of his appearance – lived his last years modestly in London, taking tranquilisers for anxiety. A smoker since his early teens, he died of bronchopneumonia and lung cancer at St Pancras Hospital in 1978, with, Stephens notes, no one else present at his bedside.

Rhys Davies was, one senses, a one-off: a man who walked alone. In some respects, his ghost – perhaps carrying his Malacca cane, the one he took with him on his trips to Porthcawl – seems to do so still… one step ahead of us thanks to the passing of the years, the going cold and overgrowing of what he made sure would only ever be the shallowest of trails.

Meic Stephens, who died aged eighty in 2018, has left us – never mind Davies’ elusive dance – with a scholarly and lively account of one of Wales’ most important literary figures – a book that is essential matter, surely, for anyone seeking a better understanding of Rhys Davies and the times in which he lived and wrote.

Rhys Davies A Writer’s Life is published by Parthian and can be bought here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.