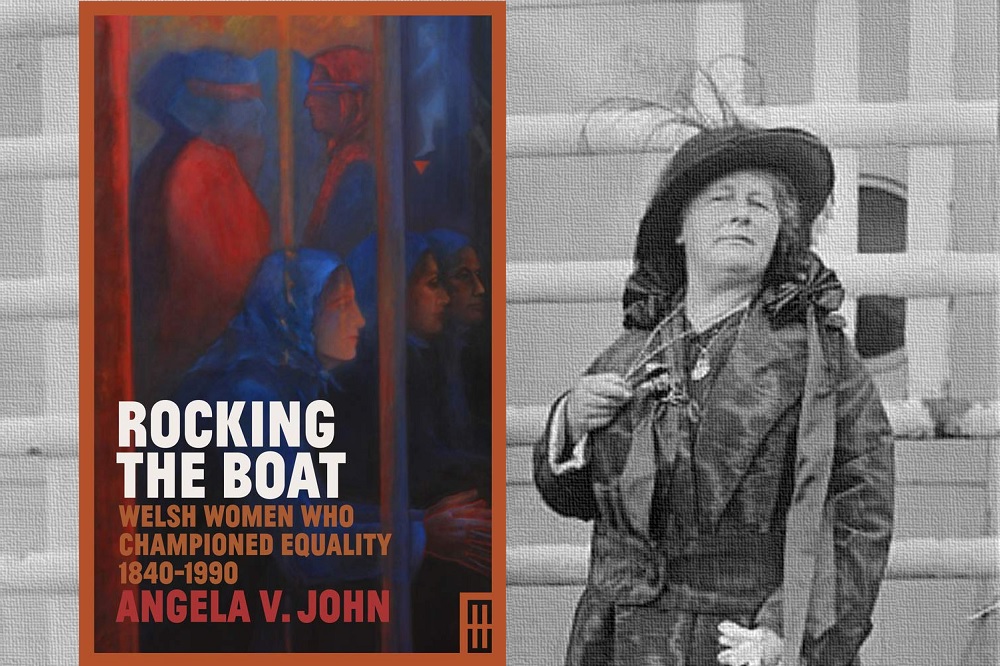

Review: Rocking the Boat – Welsh Women who championed equality 1840 to 1990

Sarah Tanburn

Rocking the Boat is a delightful read for the professional and amateur historian alike. Angela V John, honorary professor at Swansea University, has a sterling academic record and these essays are thoroughly referenced and researched. Here we have six engaging short biographies of Welsh women who campaigned for justice.

Published last year, the book has received well-deserved plaudits in many distinguished circles. From feminist historian Sheila Rowbotham to poet and essayist John Barnie, critics have found much to praise. Jones explores not only the lives of her subjects but the way biography itself works. She does so in lucid, involving language illustrating the challenges of their times.

In her introduction, Jones tells us these women demonstrate ‘different perspectives and ambiguous relationships to Wales as well as divergent models of nationhood’. The same applies to their relationships with womanhood itself. Despite those differences, there are a number of common themes straddling this century and a half of activist women.

Discussing the novelist Menna Gallie, Jones puts these connections into context. She reminds us that ‘another way of understanding [Gallie’s desire for the good community is] as an integral part of the broader meaning of political, a meaning which had a particular resonance for women.’

Jones recycles the 1970s women’s liberation insight that ‘the personal is political’, to recall the profound impact of recognising that all our lives are political, happen in ways which are shaped by our society. If we believe that life can be better, we need to change not only the political icing but the social cake.

The women Jones discusses: Frances Hoggan, Margaret Wynne Nevinson, Edith Picton-Turnbull, the Rhŷs sisters Myfanwy and Olwyn, Lady Rhondda and Gaillie, all knew this. Lady Rhondda’s campaign for peeresses in their own right to sit in the House of Lords was only won in 1963; that success had global significance, removing the final obstacle to the UK’s signature of the UN’s Convention on the Political Rights of Women. Others were formidable campaigners for the vote. Less constitutional yet just as politically constructed were the Rhŷs’s war work, Picton-Turnbull’s struggles against underage sex trafficking (then called Mui Tsai), the sideways, socialist wit of Gaillie, and much education activity.

Looking outwards

Whether extending existing political structures or working far beyond them, internationalism is a key strand. It is remarkable to see these women campaigning to improve conditions in India and Malaya, reporting on the conflicts of Northern Ireland or connecting with Black activists for civil rights in the United States.

These concerns were sometimes rooted in religion and Empire. Despite her preaching, Picton-Turnbull developed a wide range of badly needed services in India. Much as Wilberforce, the lionised champion of abolition, was fundamentally a missionary, such women improved the lives of many even while supporting the overall machinery of colonialism.

With this caveat, the evidence of Rocking the Cradle gives the lie to claims that first or second wave feminists were unconcerned with matters beyond their own class and colour. From 1919-1920 Myfanwy Rhŷs worked with war victims in remote Serbia. Alongside her pioneering career as a doctor, Hoggan was close to W. E. B. Dubois and was closely involved in improving race relations at home and abroad. Nevinson organised London dairymaids and was a Poor Law Guardian for decades. There are many other examples throughout these histories.

Such experiences also emphasise the internationalism of many Welsh families at that time. Of course, most of those overseas adventures had been military and male, but such women carved out their own connections.

Education, education, education

Education is as important in these histories as the vote itself. For all these women, access to education was itself a challenge, alongside a commitment to improving education for other women. Hoggan had to gain her medical licence in Dublin, and practiced in Prague and Paris before returning to London to work alongside Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. She also played a significant role in creating a pyramid of school opportunities for Welsh girls, not least to encourage better teaching.

Olwen Rhŷs was an early assessor for the Central Welsh Board of Education, which created secondary schools in Wales some years before a state system was introduced in England. She and her sister Myfanwy, despite prize-winning work, could not receive degrees as Cambridge University denied them to female graduates until 1948.

It is a shocking reminder to see how recently these changes came about and emphasises the importance of fighting to defend such victories. Today the UN recognises girls’ education as a fundamental development goal. We still have a long way to go but in this country we enjoy the basics of a universal system, available as much to girls as boys. Our inheritance owes much to women such as these.

Welshness

Not all these women were born in Wales and only three of them spoke the language. Welsh itself does not appear central to their self-conception, though Jones quotes Gallie, who published in English, saying ‘I wrote and spoke with a Welsh accent’.

The accent is pervasive whatever language and stage we examine, although their Welshness, their essential roles in our history and the role of Wales in their lives, is drawn elsewhere. Affinity (‘the Celtic passion for pedigree’ as Jones quotes Myfanwy Rhŷs), hiraeth, roots all count for more for these women. Their self-assertion and campaigns for social justice are both born of their conception of themselves as Welsh women, and influences the battles they pick.

I found this reassuring, as a Welsh learner. The importance and position of Wales comes from multiple sources and can be strong in different arenas, just as feminism centres women but not all feminists have the same priorities.

The women who rocked the boat were unapologetic, determined and unyielding in their commitment to fight for women, social justice and their beliefs. All of them did good in Wales and far beyond. When historians look back from the mid-21st century, what will they say about the Wales we are making today?

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Martha Maria “Mattie” Hughes Cannon (July 1, 1857 – July 10, 1932) was a Welsh-born immigrant to the United States, a s wife, physician, Utah women’s rights advocate and suffragist, and Utah State Senator. Her family immigrated to the United States as converts to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) and traveled West to settle in Utah territory with other Saints. She started working at the age of fourteen. At sixteen she enrolled in the University of Deseret, now called the University of Utah, receiving a Bachelors in Chemistry. From there she attended the University of… Read more »

The Welsh were a naturally matriarchal society and so were the celts…. but this has been forgotten in this uk obsessed and anglocentric Britain we are in

These women were struggling against a uk / english imperialist system.

norman french culture imported here was extremely patriarchal