Review: Saving Rugby Union drives home its argument with the relentlessness of a rolling maul

Jon Gower

When the former England captain Dylan Hartley’s book ‘Hurt’ appeared during the summer it portrayed a young man so wracked with pain that he couldn’t put the bins out. This follows other memoirs by warrior-class players such as Sam Warburton who retired at a young age because his ‘body couldn’t take it anymore’ as he ‘had a pin in my left shoulder, another in my left shoulder, a plate in my jaw and another in my eye socket.’

A game which has seen players bulk up and the rules soften is now far removed from what it was a quarter of a century ago when it turned professional. Muscle has replaced movement, so the sight of mercurial backs slaloming and slicing through the defence is largely consigned to memory and the new gladiatorial game leaves players down long after the final whistle. Their injury tallies can cast a long shadow, as former England player Ugo Monye explained:

‘Every morning I get up, walk down the stairs and I struggle. I’m 34. I had a groin reconstruction. I’ve got tendonitis in both my Achilles. I’ve got three prolapsed discs in my spine. We’ve got a new baby. I can’t actually bend over to pick her up. And this is coming from a winger. I wasn’t a No 8 who had the huge collisions and competed at the ruck.’

This book describes players who ‘turned into grandfathers’ on the pitch, a gruelling world where players can get seriously hurt in training alone and where a punishing calendar of matches at club and international level takes its toll. One team might put out 23 players in a Saturday game and see 17 of them report to injury clinic the following day and not be fit for training come the Monday. Head injuries in some 1,500 professional matches between 2013 and 2015 required 611 head injury assessments. In the 2017 Six Nations Scotland had seven players taken off because of concussion in just two matches. ‘Brain damage’ became a term used in discussing the effects of the game.

What’s caused all this? Commercialism? Lax application of safety rules? ‘Saving Rugby Union’ puts World Rugby, the governing body of rugby union, firmly in the dock, levelling a range of charges against it, especially for the injury crisis which has seen many players having to retire early and even, on sad and salutary occasions, left some young players dead.

Crash

Despite the fact that World Rugby chief executive Brett Gosper said that ‘the game has never been safer’ and its chairman Sir Bill Beaumont described player safety as ‘the main priority’ the evidence seems to point the other way. In March 2016 an open letter signed by academics, doctors and public health professionals argued that the game was too dangerous in its existing from to be played in schools and that ‘unless things change, even in tiny groups it will only be the big lumps who start to play.’

At a more senior level, the disproportionate emphasis on big lump physicality over free-flowing running was evidenced by the tackle rate. The game between Ireland and Wales in Cardiff in March 2017 racked up a huge total of 341 tackles in a tournament that famously ended with the farcical try line scrum-duel that lasted twenty minutes. Such statistics are marshalled to powerful effect by Reyburn as he forensically examines a game where injuries used be sorted out by the ‘magic sponge’ – being a sponge dipped in cold water – but now require medical teams and special stretchers as big men crash into big men, leading to dislocations and fractures.

As Welsh centre and trained doctor Jamie Roberts puts it: ‘There are not that many who get through their whole career without having to have an operation. I think you’re only 100% fit in your first game of rugby.’ There’s an awful lot to ponder in that small quotation.

Beef

One of the main reasons for the growing prevalence of injuries, this book contends, is allowing all eight substitutes to come into the game, thus setting fresh legs against tired bodies, making the likelihood of impact injuries much, much higher. As one of the interviewees in the book, consultant orthopaedic surgeon Professor John Fairclough describes it:

‘We gradually reached the stage where people were coming on not for injuries but because players could not last for 80 minutes. To me this is exactly analogous with running a marathon and when you reach the 20-mile mark, you get someone to finish the last six.’

This isn’t Ross Reyburn’s only beef with the rugby powers-that-be. He finds the division of financial spoils between the northern and southern hemispheres to be unfair, especially when it comes to the tiny trickle-down of money to places such as the Pacific Islands and this despite their being a veritable factory of rugby talent. Reyburn also rails against the lax policing of the scrum, and especially crooked feeds and the demise of the role of the hooker.

‘Saving Rugby Union’ is written by someone who clearly knows the game very well and genuinely worries about the direction of travel. At one point the mauling relentlessness of the polemic in play turns into a simple manifesto, a ten-point ‘blueprint for change’ suggesting rules that might have shaped the past quarter of a century rather differently. This includes a ten-year residency rule to end players switching countries with no family links and ending tackled players being able to handle the ball.

These clear-eyed suggestions and contentions all merit discussion for the sake of both the players and the game as it evolves year on year. This book might not make for easy reading for those running World Rugby but there is no doubting the passionate conviction behind the arguments it makes as ‘rugby union becomes a Darwinian perversity, with size all too often outweighing skill’ and as the current pandemic serves to probe its long term resilience as a game.

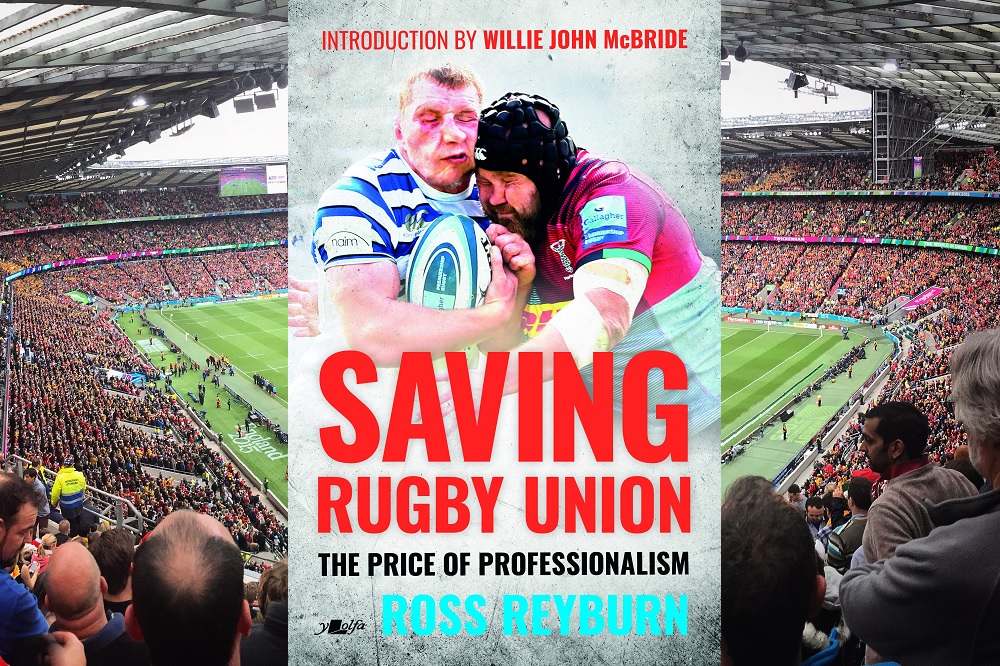

Saving Rugby Union: The Price of Professionalism is published by Y Lolfa. You can buy a copy here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.