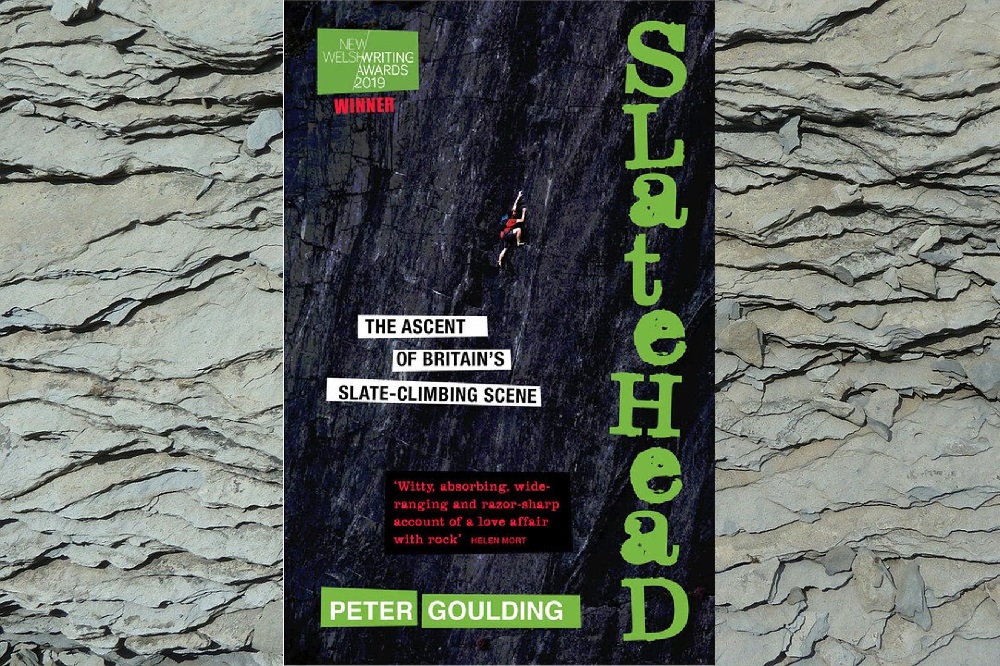

Review: Slatehead is a revealing paean to the art of climbing slate

Jon Gower

Peter Goulding isn’t an anthropologist, yet in this book he describes the life of a little known tribe that lives on high land, like the denizens of iron age hill forts, seemingly subsisting on a diet of pork pies and Jaffa cakes. These slate climbing folk baptise the routes of their ascents with cartoon names such as Mister Blister, Mental Lentils and Mynd am Aur or song titles by Talking Heads or Pink Floyd. Other names for the ascents pay homage to the slate quarrymen who created these challenging verticals in the first place, such as one called simply 362, a reference to the number of quarrymen killed by accidents.

The climbing, dangling, abseiling tribe employ language peppered with words only they understand, such as chimneying and greasing off, gri-gri and crag swag, being the climber’s equivalent to finding lost golf balls, namely carabiners and other equipment snagged on the rocks. If you gather enough swag you don’t need to go ‘shiny-shopping,’ which means visiting the gear-shops of Llanberis to buy wedges and nuts, ‘something immaculately polished, a piece of metal the size of a wine gum that could hold the weight of a Land-Rover.’

It’s a world you can only properly enter if you have a head for heights and a carefree disregard for some of society’s rules, as many of the slate faces they climb are on private, therefore forbidden land. But this suits Goulding who is by deepest nature a rule breaker. His upbringing in leafy, suburban Liverpool was full of people telling him things he couldn’t do, from red-faced farmers denying the existence of a footpath to gangs of lads telling him to get off their street. To reach the places he climbs he has to trespass and he hates the fact, but does it anyway because he has to. Climbing is a drug for him just as certainly as many of the climbers Goulding describes are no strangers to narcotics. Adrenaline is just the drug of choice but ecstasy and speed will do, or at the very least aid recreation.

When Goulding really starts to get into climbing slate he’s not exactly living in the right place, because Thetford Forest in Norfolk isn’t exactly set at an Alpine altitude. So, every so often Goulding leaves his wife and young son to head west, there to exhilarate on the hard slate faces of disused quarries.

He is not the first to venture here: he is following in the footsteps, or more properly the footholds of pioneering climbers such as Johnny Dawes, the so-called ‘Nureyev of the rock’ which can sound silly until, that is, you ‘see Dawes climb, and you get it: the shapely limbs, those straight legs and moves; the moves. They look rehearsed and seamless and it is a dance, swirls of powerful shapes, control, flowing up the rock.’ Dawes, like Nureyev jumps with grace, but in his case he does so to compensate for being short, realising he can’t reach the holds others can but rather has to jump to reach them. And this is on a sheer face, above a drop that could smithereen your bones.

Vertigo

Some of the clear-eyed descriptions of climbing in Slatehead take you to the brink of feeling vertigo. These are, after all, thrill chasers, as evidenced by some of their other delights and interests, such as paragliding and dog sledding in Arctic climes. This is writing as gripping as it gets, quite literally:

I stand on a bulge of rock, like a barrel below the cliff face. I climb, get my room through the first clip. To start with, I am on good ledges, but then on smaller and smaller crimps: narrow ledges and shelves the width of the spine of a thin book. I lock my fingertips onto them, grabbing little spikes and fins.

I put my rope through the second clip, weaving between odd zig-zag footholds. Tjhe holds are so small and I’m pulling so hard it feels barely possible but I am going up. It doesn’t feel like I’ll fall, but every time I move up I use a bit more of my strength.

Slate-climbing is a relatively recent hobby (Goulding sternly forbids describing it as a sport) and started with a bit of a Damascene moment for the influential climber and writer of guidebooks Paul Williams, who went from being scornful about slate to being one of its most enthusiastic advocates. Up until then climbers were distrustful of slate faces that were ‘cracked, loose and uncertain, fickle.’ But then some of them surmised that slate could provide good action from looking at photographs in books such as the minor classic Rock Climbers in Action in Snowdonia.

Celebrity climbers such as Joe Brown started exploring the tunnels, caverns and hewn faces of abandoned levels and quarries such as Ponc Allt Ddu, Sinc Galed and Adwy Califfornia. Some put bolts in place to make the climbs easier while some shirked such assistance, wanting to test themselves on the hardest of hard climbs, graded 7a and above. But even the waves of early enthusiasm soon disappeared as men chased their kicks elsewhere – on the Gogarth sea-cliffs, on limestone in Pen Trwyn, or out on cliffs in France. Then women started to climb and a male only preserve yielded to the talents of the likes of Shauna Coxey and Hazel Findlay. It’s a fluid and changing world, this world of the slateheads, even if the slate itself has a defiant permanence, resisting change and the sleeting Welsh rain.

Goulding stuck with the slate and in so doing came to learn about the quarrymen who blasted these places into being, the culture and camaraderie of the caban, the hut where workers would meet to eat and sing, to hold poetry competitions and debate politics.

Towards the end of this dizzy read of a book Peter Goulding says he loves having mates who are climbers because they have always done something worth hearing about. In writing this brisk, revealing paean to the art of climbing slate which is also an account of the tribe members that are its adherents Goulding tells us about the things very much worth hearing about, taking us to places many of us will never go and frankly wouldn’t have the bottle to even try.

Slatehead is published by New Welsh Review and can be purchased here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

The issue I have with climbers is that their naming of routes they have managed to clamber up is contributing to the anglicisation of our nation’s place names. For example who do you think came up with the ridiculous “Hellfire Pass”? In Porthcawl there is a small square-ish area in the cliffs whose real name is Gwter Grin-y-locs but Google Maps calls it “box bay” because some climber with all the gear on managed to climb up it. I climbed it when I was 9 in nothing but swimming trunks and green flash daps, so it’s not really even an… Read more »