Review: The Silence Project by Carole Hailey

Rajvi Glasbrook-Griffiths

On Emilia’s thirteenth birthday, her mother, Rachel Morris, sets up a tent at the bottom of the garden and stops speaking. Eight years on, in a coordinated act named the Event, Rachel and twenty-one thousand of her followers from across the world burn themselves to death.

What began as a Greenham Common like protest has snowballed into the Community, a powerful global movement with influence and reach in every sphere of public and private life. The line between cult and culture is opaque even if the Community’s exclusively sinister message is ruthlessly clear: ‘those who are not with us are against us’.

The book opens with Emilia setting out to publish her mother’s notebooks and in doing so to emerge from that all-pervading legacy, to set down her own voice.

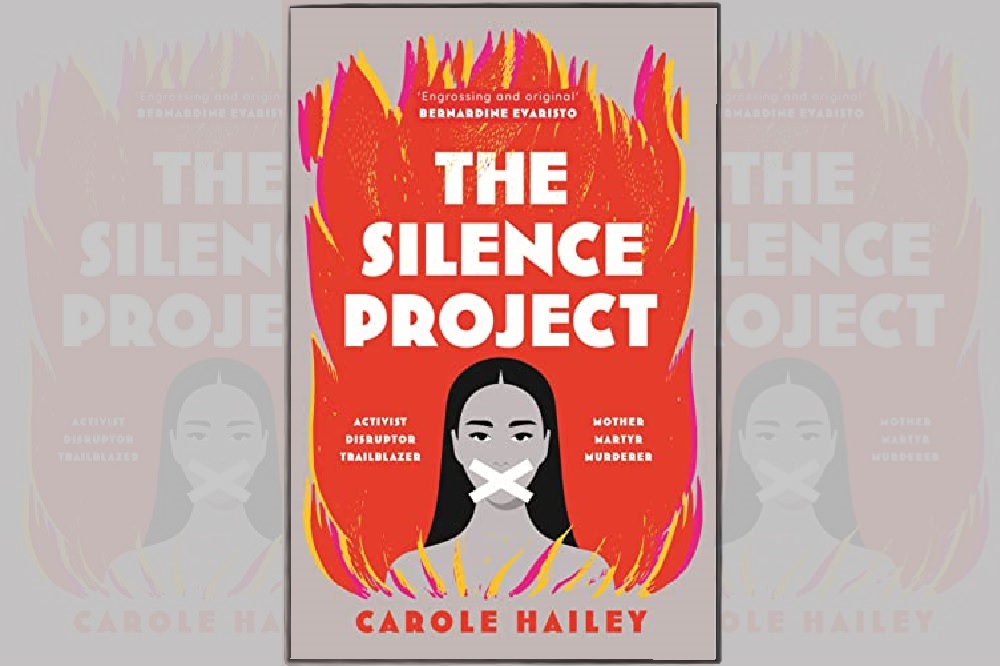

The Silence Project is Carole Hailey’s debut novel. It is as terrifyingly relatable as it is dystopian, as multilayered and philosophical as it is grippingly compulsive, and as much reminiscent of writers such as Margaret Atwood, Naomi Alderman and Miriam Toews as it is inventive and original.

Polarity and protest

This intelligent balance also plays out in the novel’s themes. The cover boldly sets Rachel out: Activist, Disruptor, Trailblazer, Mother Martyr, Murderer. As we read her, she further emerges as many other things too, not least a woman lacking and seeking purpose, in need of peace and space to make sense of her life, and a human being deeply sensitive to the state of our world. The world is manically, discordantly noisy and no one is listening to anyone else, and so Rachel wants to listen. Moreover, she wants to hear.

Hailey writes in a way that continually negotiates and challenges our perceptions and boundaries: between protest and responsibility, silence and voice, listening and hearing, the particular and the universal. In her novel, ‘Spring, Ali Smith writes of boundaries not as places where two places separate, but as where two points meet and meld, and this resonates here. Rachel is many Rachels.

‘It was a bit wearing trying to anticipate which mother would make an appearance on any given day…,’ writes Emilia.

Eventually, Rachel abandons being a mother altogether for what she deems a higher purpose. This will sit differently with each reader. Are mothers mothers above individuals? Does a utilitarian sense of purpose override personal responsibilities? Are our answers to these the same for women and men both?

Rachel’s messianic shadow looms heavy on all that happens after her, over the global actions of the Community as well as the lives of her husband and daughter. She is at once a malicious eminence grise and a scapegoat open to the projections of all.

In our current global state of perpetual crisis, agendas collide and powers clash. Whilst rights are not pie, rights can indeed conflict. One such very disturbing ethical issue ends up facing Emilia directly when she becomes involved with the Community and goes to work in the Democratic republic of Congo.

Questions

The narrative throws up many other questions too along the way, the kind with no clear answers. Is silence really silent if words are still communicated through technology? To what extent is the internet integral to modern protest movements? Certainly in the case of recent events in Iran the internet has been a vital vehicle for communication. Moreover, movements such as Extinction Rebellion rely heavily on social media to garner support.

Whatever the nature of the cause the internet, like the very act of protest itself, galvanises as much as it polarises, and both regularly take on radical centrifugal momentums of their own. The exponential nature of this is well charted and portrayed here, and apportioning of responsibility depends on the moral question of where does Rachel as the founder end and the community begin, or are they the one and same?

In such a dissonant and polarised world, Rachel who relinquishes her voice for silence has left herself entirely open to interpretation.

Hailey effortlessly incorporates fictional citations, reports and academic references to powerful effect. Descriptions of ‘The Daughters of the Redundant Voicebox’, a group of women having surgery to induce vocal-cord hemorrhage, and the ‘Johnson-hill detentions’ are profoundly uneasy, but they are also not too removed from the type of more and more alarming newspaper exposes that less and less shock us in recent times. ‘But here we are in the prequel. We’re in pre-hell. This is how it begins,’ warns Emilia.

Discords and cruelties

Emilia’s relationship with her mother is inevitably full of resentment and very broken. Some of the disappointments have long preceded Rachel’s silence and protest. In those more ordinary discords and cruelties we see a reflection of the flaws in a mother-daughter relationship that are either universally human or the incipient beginnings of Rachel’s future actions to come.

The ending returns the reader to reflect on what it can mean to be a mother and a daughter, and the vast terrain of expectation and love that stretches between the two.

It is also a very loud message about the power of words, both silent and spoken, and about the choices we make, since consequences have their own ripples and sound.

The Silence Project by Carole Hailey is published by Corvus, Atlantic Books. It is available here or from all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.