Review: Truth, Lies and Alibis, Encounters with Christine Kinsey

Ric Bower

In Truth, Lies and Alibis, Encounters with Christine Kinsey the artist describes, with a disarming matter-of-factness, her childhood in post war Monmouthshire punctuated, as it was, by a plenitude of upsets. Scarring illness, surreal hospitals and the death of her father all blended with a selection of otherworldly elderly relatives.

Even her description of the school long jump is surreal, her runup beginning (almost) outside the premises culminated in a jump of Hogwartian proportions in the school gym; an approach that led to her breaking the Monmouthshire record.

Meaningful

Her text is interspersed with pictures, none of which are dated, making it hard to establish a meaningful dialogue between the two.

We are offered clues to the awakening of her political spirit and given an insight into the mystique of art schools before they were fooled by fake universities into making the students customers. (Not that they were idyllic in the early sixties, according to Kinsey they were full on sausage fests).

There is a magical photograph of Kinsey, with her partner the artist Bryan Jones in Trafalgar Square, when the couple had moved to London in the early sixties; a pigeon is just getting airborne in the foreground in front of them, all blurry and suggestive.

Kinsey describes the expectations and limitations placed on her as a woman artist; she lays out the road ahead for her, as she saw it, one that it is impossible to imagine will not contain struggle.

Mystical

For the second half of her book the focus is, for the most part, on her painting and drawing. The work is often slightly out of reach, so mystical that many of the possible points of access are sealed, if you are coming at them cold that is.

Her connection with Russian icon painting, on her own admission, is strong, and this is useful knowledge. With icon painting the underlying narrative is shared and communally understood though, which is often not the case with Kinsey’s work.

I was however completely bewitched by her monochromatic work, (and perhaps this is aided by how well it reproduces).

The etchings she produced in Sint Maarten, studies of a naked woman with spectacular bird headdresses are brilliant on so many levels, from the rhythmic mark making to the glowingly open tonality and that is before we even begin to discuss what it all could mean.

They could easily be the inspiration for the contemporary Swedish fusion band Goat’s on stage headgear.

Wonderful drawing

But let’s turn from the the finished works though, (well for the moment anyway), let’s hear Christine’s voice, let’s revel together in a wonderful drawing.

Executed while she was still in art school (I think, no date) it’s bursting with the arrogance of youth; see the muscular composition, the biting incisions of an individual who is not content to leave the world unchanged, an individual who has a profound affinity for space.

If I was into my second drink I might even call that student drawing prophetic…

A new Chapter

The full force of Kinsey’s political energy is brought to bear bringing into being an art centre in Cardiff in 1972, Chapter. She describes putting on a promotional festival in Sophia Gardens with Black Sabbath on the bill…BLACK SABBATH for fucks sake!

Of standing next to the fearsome head of the Cardiff Drug Squad at the event and him whispering to her, through a haze of hash smoke, ‘If you keep all this in here I’ll ignore it…’

Between the lines of the cheerily related arty anecdotes (most of which begin with her finishing off some tiling, or fixing a Chapter floor malfunction) are glimpses into the hard decisions, the business planning and the sheer grit Kinsey and her collaborators brought to the table to bring their impossible vision into being.

Perhaps my awe is deeper because I have benefited from having a studio at Chapter for the last decade. Or maybe it is because I have tried, and failed, to set up a combined art school and art centre. I know how hard it is to sit around a table with folk whose agenda is completely alien to you.

Spectacular

She speaks of their intention, in the new art centre, to break down the barriers between the disciplines in the arts and to build a space that facilitates this end; we can only wonder at how it has taken the best part of half a century for other institutions in Wales to catch up.

Only once does she mention the ‘severe personal financial problems’ her and her partner Bryan Jones were experiencing at the time; the price of wonder is always high.

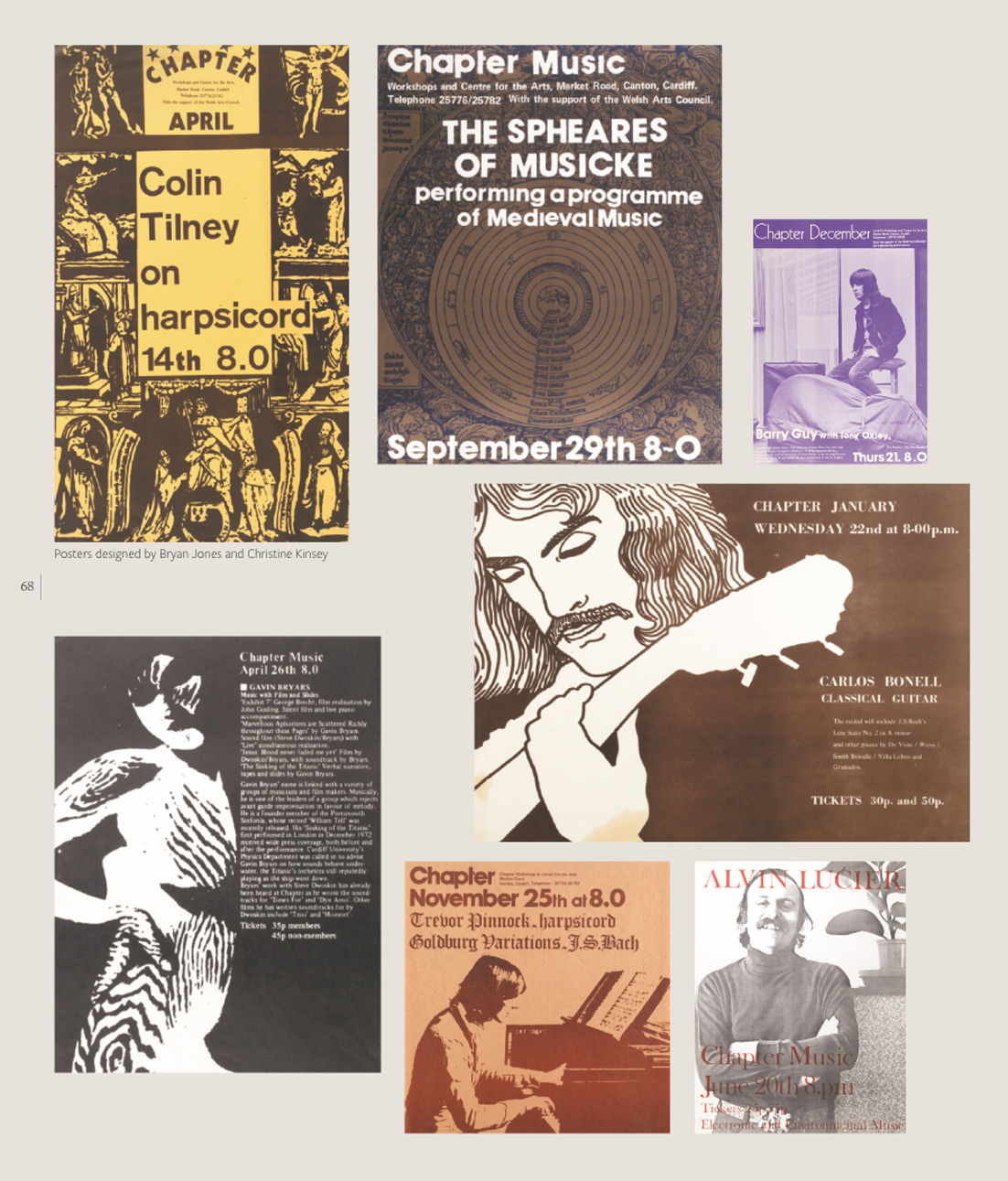

Bryan Jones’ and Kinsey’s posters, designed for the early years of Chapter are spectacular, in any other situation they might be celebrated in their own right, but in the context of what Kinsey describes as one ‘…enormous installation with live art in real time’ they are just a small piece of the puzzle.

Kinsey goes on to have a distinguished career after Chapter, and I do not mean this as a euphemism for respectable but dull. The common thread seems to be her willingness to take risks and that she consistently advocates for the under-represented, be that woman artists in Wales or school children in the Caribbean.

Kinsey, throughout her career, advocated for women artists beginning in a time when the gender imbalance, in any of the many art worlds, was even more shocking than it is now.

I am not sure if an entrepreneurial, anything-is-possible attitude is still present in Chapter in 2023, maybe it has just grown up, such questions are above my pay grade.

But surely it should show us how important it is, as a nation, to continue believing in the impossible and support organisations like Shift Cardiff in the Capitol Centre which runs today on a similar kind of Raw Power, the kind of energy that Kinsey would recognise.

Activism

A monograph has the ability to slice an artist’s practice like a microtome,and then to take those slices of influence, reproduction, historical reference and memory and juxtapose them. It’s still strange though that authentication of the lifetime’s work, of any artist, finds expression pressed between the boards of a book, particularly that of such a vibrant character as Kinsey.

But like seeing pressed flowers, the experience is never quite the same as feeling the work first hand in the wild. And then there are always those introductory essays to wade through, like the interminable speeches at a gallery private view, they claim to elucidate, to offer the keys to understanding, but sadly; (unlike in the gallery), we can’t shuffle off to the bar until they pass.

To bastardise Jesus: ‘For you shut up the ‘Creative Realm’ against folk; for you neither go in yourselves, nor do you allow those who are entering to go in’. But yes, I do understand, I have had this God awful hangover from an excess of modernist moonshine too.

High on moonshine it seems perfectly right that we examine Christine Kinsey’s painting and drawing practice in isolation—from her life, her activism, from her character. (I have a list of weird things I have done when high by the way, if anyone is interested).

If we do so though, it is in direct contravention of the evidence, that is fortunately still plentiful, in Truth, Lies and Alibis, Encounters with Christine Kinsey.

Truth, Lies and Alibis, Encounters with Christine Kinsey is published by the H’mm Foundation and is available from all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.