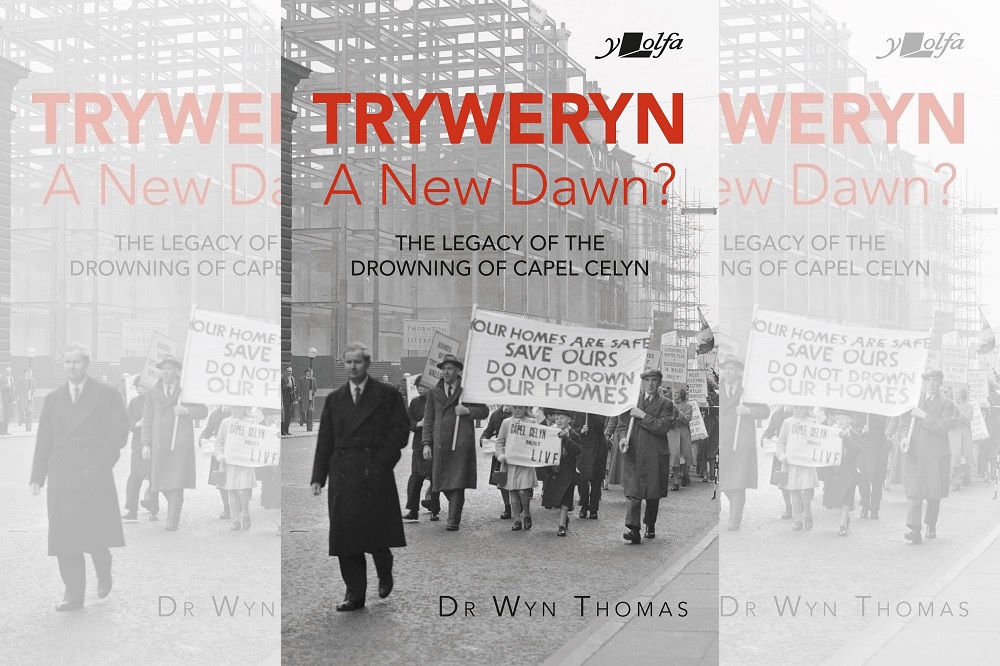

Review: Tryweryn, A New Dawn? The Legacy of the Drowning of Capel Celyn by Wyn Thomas

Niall Griffiths

In 2008, on the BBC evening news, Liverpool Councillor Storey offered this apology to the displaced of Capel Celyn: ‘Liverpool has a very strong Welsh community still [and] I think it’s important to the links between Liverpool and Wales that this apology is given. I hope that people don’t see it as just a gesture, it certainly isn’t, it’s about recognising the mistakes that were made in the past’.

From the august Council Chambers, the programme cuts to a pub in Hackins Hey (not named, but I recognised it), a cobbled ginnell in the Cheapside business district which houses two of the city’s oldest pubs, frequented by local office workers on their lunch breaks.

One such – buttoned up, crisp white shirt, trained hair, generic nowhere accent – says of Storey’s apology: ‘I think it’s a total waste of time, energy, and the city council should be doing something more important than making forty-year-old apologies’.

Then an older guy – the furrowed face, dark and impassioned eyes, thick local accent – says: ‘I think it was a liberty, what they done. What rights have any council, any town, got to take the identity of another town, in another country, away from them? They have none’.

Readers of my Real Liverpool may recognise this vignette, and it’s not one referenced in Wyn Thomas’s book which is surprising because, by God, everything else related to the flooding of the Tryweryn valley is: it’s encyclopaedic, huge, a staggering feat of research, a Herculean labour.

I cannot imagine a more extensive and informative reference work on the subject than this.

Brute power

You’ll be aware of the story, no doubt; that, in the middle of the last century, Liverpool council forcibly displaced the inhabitants of the Tryweryn Valley in North Wales so as to create a reservoir to irrigate the city.

The purported reason was to supply drinking water for the populace of a city still ravaged by Luftwaffe bombing; the truth was that much of the water was needed for industrial development, and to sell on. It is, at base, another instance of the brute and raw power of capitalism.

Colonialism

Except, of course, and in this instance, it carries the taint of colonialism; this was an English council yet again imposing itself on a Welsh locality.

Thomas’s theme is basically that it was this event which, more than any other, prompted Wales into modernity – that is, into a refreshed notion of national identity, newly politicised, even militant, forced into an awareness of itself as a constitutional adjunct of a more powerful neighbour and so in direst need of sociopolitical awakening.

‘I believe’, he writes, ‘that 31 July 1957 – when Liverpool Corporation’s Tryweryn Reservoir Bill received its third and final reading in Parliament – was the date when the geopolitical architecture of modern Wales was created’.

A grand claim which requires grand evidence, and Thomas supplies it.

Fury

There are times when, undoubtedly, the torrent of statistics and lengthy quotations becomes trying and, even, a distraction from the narrative, but Thomas’s overriding concern is with balance; the loss of land, say, is always put on a scale against the supply of water to irrigate other, more richer land.

Yet he never – and, in my opinion, to his great credit – allows practicality to overshadow what was essentially an act of ‘ethnic vandalism’.

So the dryness of bureaucratic governmental diktat is set in contrast to the horrific exhumation of graves in Capel Celyn cemetery; the bloodless tabulations and calibrations of water requirements are presented alongside the fury of the crowd at the official opening of the reservoir.

True, there are times when what feels like acres of text separates such oppositional moments, but that’s Thomas’s style; he sets up thematic moments, and personages who embody them, like hot wires which run through the entire tome (and if there’s one book I’ve read recently that warrants the grandiose term of ‘tome’, it’s this one).

Exploitation

Take Bessie Braddock: heroine of the left, scourge of the Tories, firebrand, fierce, impassioned orator, there’s an imposing statue of her on Lime Street station concourse, yet she was an enthusiastic supporter of the drowning of Tryweryn; Lord Morgan said of her that ‘she had little understanding with regards the national identity and aspirations of the Welsh nation.

I don’t believe that this was born of a lack of respect for Wales. It was simply because, I suspect, she regarded Wales as a far-off and distant land full of far-flung Liverpudlians’.

Hmm. A ‘distant’ place? Even in the 50s, she could’ve travelled to Wales by train in an hour. And ‘lack of respect’? Well, an unwillingness to educate oneself out of a false notion pretty much conforms to the definition of ‘lack of respect’.

Braddock’s socialism was of the kind that sought to transcend borders and adhere to the commonality of downtrodden class, so nationalism was anathema; I get this, but I agree with the writer William Vollman here, that (and I paraphrase), nationalism in a large country is about oppression and exploitation whilst nationalism in a small country is about self-autonomy and independence and a type of freedom.

Thomas, I suspect, agrees with this too.

Predatory

And that, indeed, is the mortar of his book – the legitimisation of nationalist feeling in Wales (altho I do baulk at that word, given its connotations: ‘independence’ is less problematic, and more accurate), inspired by the flooding of the valley.

The career of Gwynfor Evans is given extensive study, and equal space is given to both his detractors and supporters.

The monkey-wrenching of the diggers and engines at Tryweryn is seen as the precursor to Meibion Glyndŵr’s arson campaign; indeed, the MAC (Mudiad Amddiffyn Cymru) as an organisation is presented as presaging MG.

And the echoes: the Rebecca riots; Lake Vrnwy; the relocating of some Capel Celyn residents to Frongoch, where some Irish fighters were held as POWs early in the last century.

The characterisation of Wales as a place of running water, and how that most essential of resources has drawn the predatory capitalist.

Congregation of eels

If the book does contain moments of bloodlessness, then that is the nature of the evidence it adduces. Essentially, its tone is that of tempered anger.

The flooding of Tryweryn was not on a par with Bloody Sunday, or the Shatila massacre, or the carpet bombing of Vietnam (and opprobrium on those who ever make such false equivalences); but it will remain as emblematic of the savage entitlement of establishment capitalist power (astonishing really that the likes of Braddock couldn’t see this).

Thomas has a chapter on the reaction of artists to Tryweryn; a short section, but a powerful one.

The event, and the place, has become central to the stories that Wales tells itself about itself; it will continue to fulfil that function. The reservoir waters will stay dark and still and the sunken Chapel will have a congregation of eels.

Let me return to that pub in Hackins Hey, and the man with the lined face and dark eyes. Indulge me in suggesting that, as Tryweryn awakened and enlivened Welsh identity, so it did that of Liverpool, in a fascinating cultural symbiosis; of late I have noticed that its pride in itself as a city of sanctuary and fierce defiance against entrenched ideologies of power has, of necessity, demanded a reckoning with its history of importance to the slave trade and, too, as a city of empire, and the Tryweryn episode has become part of that (the recent ‘Scwelsh’ poets frequently reference it).

A city in but not of England; a city that shares more with the Celtic countries of the archipelago than the Anglo one it is nominally a part of (get on to Youtube and search for ‘Scouse not English’, but best not do so in earshot of someone of a sensitive disposition).

Thomas concludes that ‘out of the anger and frustration of Tryweryn, Wales emerged stronger: both politically and culturally – and perhaps, consequently, more confident than ever before’.

His work is very persuasive on this notion, and I’d suggest that it applies, as an ingredient, to Liverpool too. So, Councillor Storey, as well as sincere regret, you should perhaps also express gratitude.

Tryweryn, A New Dawn? The Legacy of the Drowning of Capel Celyn by Dr Wyn Thomas is published by Y Lolfa. It is available from all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

I found this article very informative. I was particularly struck by the fact that the apology from Liverpool City Council came from Mike Storey who led the then Liberal Democrat administration and how that contrasted with the attitude of the Socialist Bessie Braddock. Would a Labour led administration even have thought of apologising?

In 1957 my home City Lerpwl had more Welsh chapels than all the cities of Wales combined. Plus I think a good many of the Corporation were Welsh speakers. Stretches colonialism a bit far. Lerpwl prif ddinas Cymru once home to the National.

Did the Liverpool Welsh community support the campaign against the drowning?

I don’t know is the honest answer. I suspect they were ambivalent. It’s the bit about Colonialism that made me comment. If anything Lerpwl at its height with 100 Welsh chapels was a Welsh colony in Englad.

Hardly. More like Cymry were drawn to Lerpwl by the prospect of work and a decent wage which might not have been available in their home patch. People from most of the colonies were drawn to UK/GB at some time, as they were part of the mass of resources sucked out of the colonies by the imperial centre. Happened in Birmingham, Manchester, Bristol and of course London.

9

It is clearly a painful time in Welsh history. But in the analysis never do I read about the destruction of swathes of Liverpool during WW2 bombing which lead to a deeply impoverished city, with a huge need to regenerate. Thousands of people needed to be rehoused and jobs created for them. Mostly rural Wales could turn their backs on their near neighbours with no feeling of a debt of gratitude for Liverpool’s role in the War. They might have housed a few snotty nosed Scouse evacuees but compare that to the loss of life of civilians and seamen, and… Read more »

Hello Jan, Can I refer you to ‘Tryweryn: A New Dawn?’, please, which comprehensively covers the savage bombing of Liverpool. Notably, the dreadful 8-day attack in May 1941 (included in both the main body of the text and the appendices). Indeed, all the issues mentioned by contributors in the comments outlined above are addressed. Thank you, Wyn Thomas (author).

As for your closing comment regarding ‘nursing grievances’, this too is highlighted in ‘Tryweryn: A New Dawn?’ (the final pages of the conclusion). Can I recommend that you read the ‘Tryweryn: A New Dawn?’ please. I think you might find it useful. I’m thrilled by how much the book has received praise for its ‘fairness and balance’ (a quote). Thank you, Wyn

I look forward to reading this book and its opinions and references. Its time for some revision of the current discourse. Rhodri Morgan always tried to down play its impact plus that of the Mynydd Epynt clearances in “ Brecnock “. Certainly the current “ histories “ imply a united local community with one view and the buldozer of Liverpool v Cymru Bach. More recent evidence ( oral evidence ) offer a less clear cut situation also some family splits; views that better land via compensation and new chances and opportunities for less well of rural folk. Revision or reinterpretation… Read more »