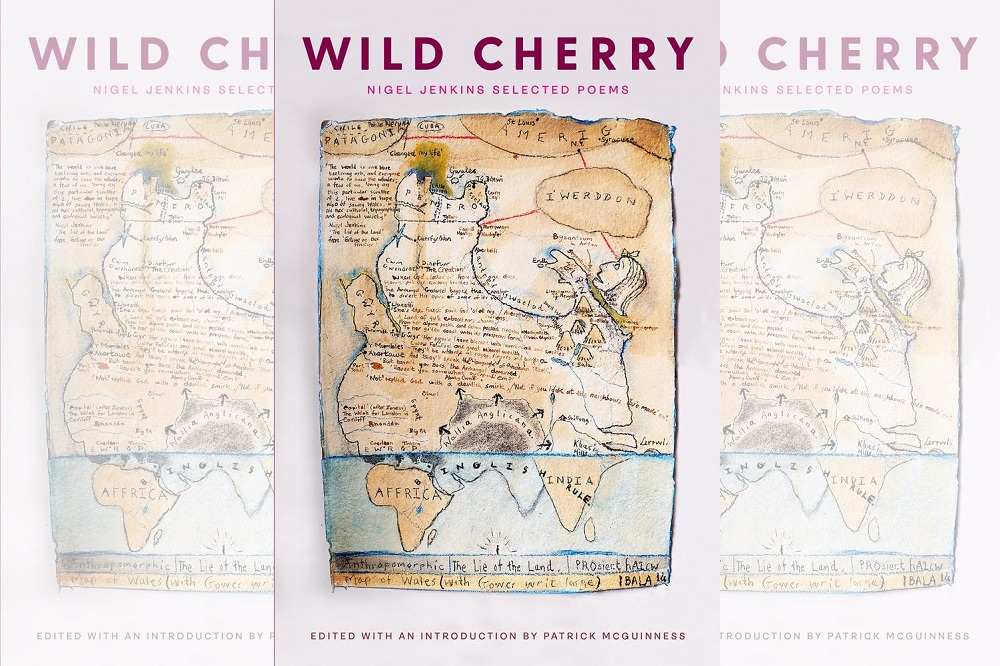

Review: Wild Cherry – Selected Poems by Nigel Jenkins

Topher Mills

Nigel Jenkins has a staggering presence in the literature of Wales. His poetry is both political and beautiful, deeply human, wonderfully cosmological of often scathingly humorous. Swansea’s most amiable bard and, undoubtedly, its most popular poet since Dylan Thomas.

I first met Nigel in 1982 when he was a guest reader in Chris Torrance’s creative writing class. To hear him read his poems was to hear one of the great reading voices of Wales.

There’s Dylan, Burton and then there’s Jenkins. ‘Voice like the rumbling ocean floor’ as one lesser poet described. He was the epitome of the deep voiced, bearded, swarthy, Celtic bard, almost stereotypically so, and he really made it work for him.

The ancient bards, like the ancient Greek poets, would be taught how to orate in the halls and courts of lords and princes, but they would also, and few note this, know how to sing on the village greens or in the taverns for the ordinary folk, the gwerin.

Poets nowadays just tend to mumble to one another, but Nigel, following in the footsteps of the other great Gower poets Cyril Gwynn and Harri Webb, could perform for everyone, could project that glorious mix of humour and passion that can make an audience come alive.

It is so good, therefore, to see a popular paperback selected containing his best and his most entertaining work.

Real heart

This does make him sound like a light comic poet, but he was just the opposite, a seriously fine poet whose work always had real heart.

His early poems here are of the tough, hardness of growing up on a Gower farm. Sculpted from experience they are as good as anything by R.S.Thomas or Ted Hughes.

Here’s his poem ‘Castration‘ about being coaxed by farmhands when young to turn a bull into a steer;

‘It didn’t hurt they said

as they caught and threw them

locked each scrotum

for a second

in the cutters iron gums.

The next one was mine…’

When Nigel read this at one event a listener passed out at the vivid horror of it.

Vocation

In finding his vocation he gradually left the farm and the poems filled with work, family, loss, his father’s death and the anger of the 1979 vote against devolution.

In ‘Land of Song’ he wrote about;

‘Oggy! Oggy! Oggy!

shame dressed as pride.’

and his poems after that period were far more honed, almost sparse, open field, modern and suffused, in the days of CND and Greenham common, with the ominous nuclear threat.

His two long poems, ‘Snowdrops‘ and ‘Warhead‘ lit up the poetry scene of Wales with the possibility of moving people politically, not with rants and diatribe, but with gentleness and beauty.

He imbued many of us with the idea that even political poems should be good poems first and foremost.

Humour

This is not to say that he couldn’t, occasionally, summon up a riotously bumptious sense of humour to make a telling point. Poems like, ‘Never Forget Your Welsh,’ ‘Byzantium in Arfon’ and, infamously, ‘An Execrably Tasteless Farewell To Viscount No,’

‘White man’s Taff

And blathersome stooge of the first ‘order!’

Orgasmic in ermine

May his garters garrotte him.’

Which caused a sensation and got him on the front page of The Guardian. (When they asked if they could quote it, he said no. They could print the whole thing or nothing. So they printed the whole thing.)

In later life he produced gleaming haiku and other quirky miniature wonders. In these A.I. infested times his poem ‘Hello‘ imagines an advanced alien species sending us meagre earthlings a greeting;

‘Your knowledge, though, gallops beyond

your wisdom – we speak from ancient experience

survivors ourselves of the techno-moment.

You are at a familiar turning point,

but don’t expect us, who learned at last

to live with ourselves, to drop in and sort you out.’

Acute insight

His range was galactic, from small literary nuggets to the magnificent tour de force of poems like, ‘Forty-Eight and a Half,’ in which he writes about passing the age at which his father died and the two of them riding on horseback through time in familial love.

The final work is the small epic, ‘Advice To A Young Writer,’ in which he distils years of teaching creative writing with deft humour and acute insight that is the most marvellous gift to the future of literature.

Nigel Jenkins was one of those men who form communities. Women form communities, but rarely men. The Gower and the Swansea valley was his community and at practically every literary (but especially poetry) event, he was there, supporting it as a stalwart of the scene.

When I go to Swansea now it still feels odd that he’s not there. I know I’m far from being the only one who feels that way. In a way though, he is there, in the ebullient literary community, one of the foremost in the country, that he helped to create. The positive effects of which we are still enjoying.

This selected poems, edited so very well by Patrick McGuiness, is an absolute triumph!

Wild Cherry: Selected Poems by Nigel Jenkins, edited by Patrick McGuinness is published by Parthian. It is available from all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.