Rory Gallagher and the invention of Irish rock: A celebration for St Patrick’s Day

Desmond Clifford

There’s an argument which says the smaller the country, the more marked its divisions. Ireland’s division is, of course, marked on the map and, as WB Yeats noted, “Great hatred, little room.”

Even so, the country is loyal to a single rugby team and the ecclesiastical capital, Catholic and Protestant, is Armagh in the North (with its two cathedrals named for St Patrick in a city of 16,000).

With the exception of St Patrick, for whom the late Rev Iain Paisley was an enthusiastic advocate, figures who are admired equally in all parts of Ireland are few and elusive.

In the spirit of St Patrick as a symbol of unity, I offer guitarist Rory Gallagher, arguably Ireland’s first and greatest rock star.

Show bands

Rory emerging in 1970s Cork had that specialness that always attaches to the first of a kind.

At the time of his flowering Ireland had no rock music industry, no guides, no stars, no managers, no venues. Nothing, only an Irish youth disenfranchised by show bands and a stale cultural offering. Rory’s extravagant talent created something new.

He was the first and greatest of Ireland’s rock stars, not measured in record sales – that’d be you, Bono – but by virtuoso skill, the admiration of other musicians, durability with his fans and legacy.

Where did that exceptional talent come from? Did the boy Rory meet the devil one evening at Ballyshannon crossroads? Like all great achievers, he saw beyond his immediate borders. He ached to join what Elvis and The Beatles had unleashed, however unpromising the scene in Cork.

Mere geography couldn’t stop his journey to the delta blues, as he reached the Mississippi via the River Lee. Young Rory bought his records at Eason’s in Cork from Sheila MacCurtain, daughter of the city’s murdered lord mayor, who apparently fed his interest and procured specially ordered blues discs otherwise unavailable in Ireland, in true revolutionary style.

All-Ireland

Rory was a rare all-Ireland figure, as popular in the North as the rest of Ireland. He was born in Ballyshannon, Donegal, lived for a while in Derry and grew up in Cork. Through the worst of the Troubles he repeatedly played the Ulster Hall and other venues in Belfast while others gave it a swerve.

He made no political statements, but playing Belfast when nobody else dared, and “dared” seems the right word here, was a magnificent gesture of civilization and solidarity. Rory flew by those “nets”, as James Joyce would have it, of church and country.

He planted his flag in the Republic of Music where citizenship is open to all.

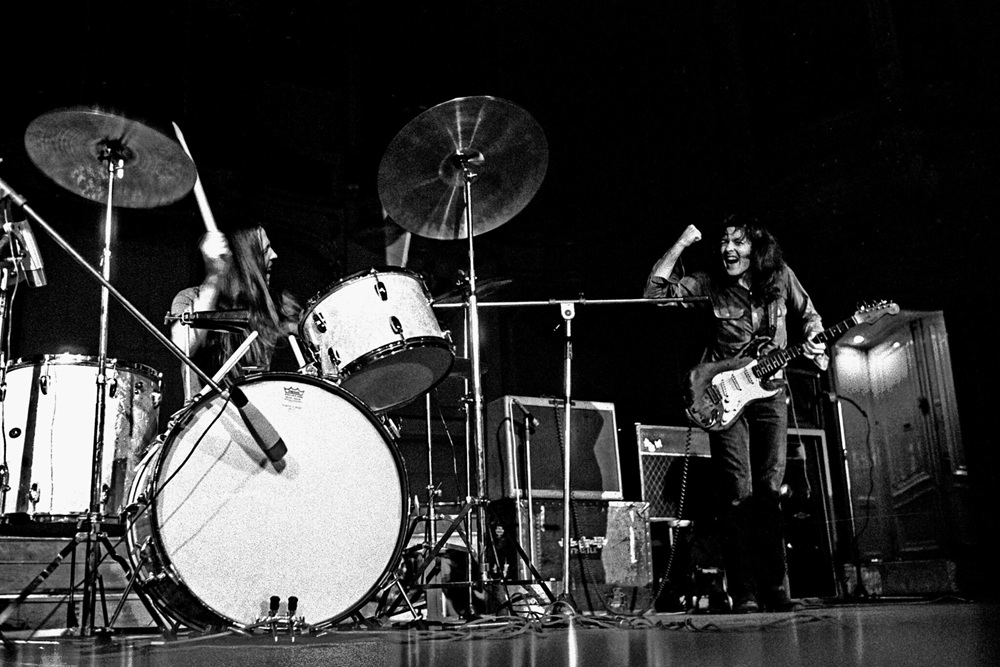

There is film footage of Rory as a young man in Ireland. He comes across as sweet and natural and humble, which only magnifies the sadness of his later more melancholy years. Go online and see him play at any time in the 1970s.

You will see no man happier in his work. There is none of rock’s angsty posing. Image was immaterial to him, the guitar was everything. A huge smile repeats over his face as his fingers dance across the fretboard with a wizardry that even he seems delighted and surprised by.

Rory’s later struggles were exacerbated by the industry he worked in. He succumbed to alcoholism, a kind of signature illness for Ireland after the conquest of TB.

Illness

Rory was further weakened by illness, prescription drugs and poor mental health, all compounded by poisonous relations with record companies. He died after complications from a liver transplant at the wastefully young age of 47.

Rory was the guitarist’s guitarist. Slash, the Edge, Johnny Marr, James Dean Bradfield, Brian May, Eric Clapton, Joe Bonamassa and, it is said, Jimi Hendrix, all acknowledged his influence. Heaney and Beckett were scarcely more influential in their fields.

After his early death in 1995 Rory’s reputation slipped somewhat into the shadows. Ireland found new stars who conquered the world. In later years Rory’s brother Donal took charge of his legacy and his reputation revived. His records were remastered and re-released and fresh material unearthed which gives his music a freshness and classic status. His birth town, Ballyshannon, hosts an annual festival in his honour.

I came quite late to Rory. My friend Damien, originally from Belfast, got me into him. We’ve been swopping books and music for years. He kept pressing Rory discs onto me and I only vaguely listened so I could look him in the eye when I shrugged in a non-committal way as I gave them back. “Heavy rock”, as we used to call anything where a loud guitar is central, wasn’t my natural thing, but Damien’s gentle advocacy eventually won me over and I began listening with open ears. Then I started getting my own collection.

I remember my brother going to see Rory in concert in the late 70s. I don’t remember if he invited me but, if he had, I’d have said no – my head was full of Rick Wakeman and Emerson, Lake and Palmer. Wasn’t I the eejit? I regret it now, of course. How I’d love to have seen him in his prime.

After half a century it is really remarkable how undated his music sounds. Rory was all about performance and his live recordings are better than his studio material. My personal favourites are “Follow Me”, “Daughter of the Everglades”, and “A Million Miles Away”.

I texted my friend Damien for his top 3 and he replied: “Tough one. But today I will go for ‘Moonchild’, ‘Walk on Hot Coals’ and I Fall Apart’. Ask me tomorrow and I could easily come up with another 3!” I know the feeling…mention of ‘I Fall Apart’ already has me thinking again. Any Rory fan could pick a “top 3” 10 times over, so rich is the catalogue, and much animated conversation is sustained by this pursuit wherever two or more admirers are gathered.

Statues

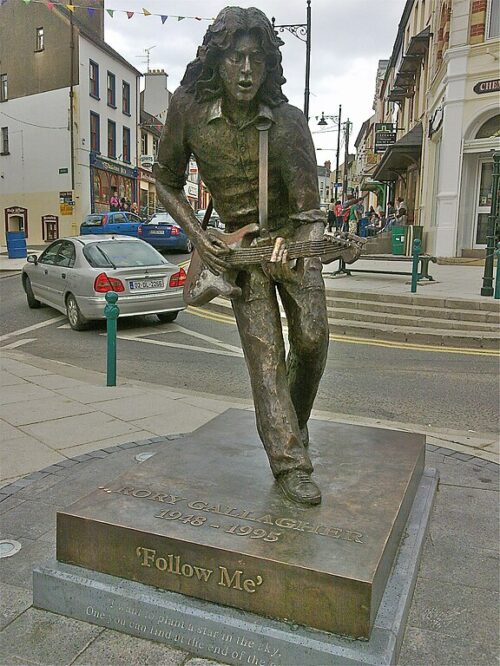

There are statues or plaques to Rory in Ballyshannon and each of Cork, Dublin and Belfast. This is unique. No other Irishman is so celebrated in each of the county’s three major cities north and south.

The Edge was present at the unveiling of the memorial at Rory Gallagher Corner at Dublin’s Temple Bar. You can visit Rory Gallagher Place in Cork and see the life size bronze statue in Ballyshannon. A statue outside Ulster Hall in Belfast was unveiled just weeks ago. Near Paris you can find rue Rory Gallagher; Rory’s popularity in Europe was solid and he lived for a period in Ghent.

As a teenager in 1963 Rory paid the then enormous sum of £100 for a second hand 1961 Fender Stratercaster (Sunburst Model) from Crowley’s Music Centre in Cork.

This purchase changed his life and ours, his fans. Rory’s leap of imagination enrolled Ireland into the international community of rock so that those who followed him – Thin Lizzy, Undertones, Stiff Little Fingers, U2, Hothouse Flowers, The Murder Capital, Fontaines DC – came from somewhere and belonged to something.

This is the claim for Rory Gallagher on St Patrick’s day. That the quiet and unassuming genius from Cork touched lives across Ireland and far beyond, that he is a treasure as precious as Yeats and Heaney, that he represents the best of Ireland in a medium celebrated across the world.

Happy St Patrick’s Day!

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Wonderful guitarist. I bought his albums in the 70’s. I also bought a sunburst Fender Stratocaster in the 60’s as well (it was a 63 model which I bought in 1967). The main difference between the two of us is that he could actually play – brilliantly.

I don’t remember ‘Man’ getting a mention on here, I believe ‘they’ are back on the road…

‘Man’ at the Roundhouse, a second home. The staff from the Roundhouse had a Commune not too far from Rockfield back in Cymru…!

It was like the Marque on Wardour Street for me, we had a building a few doors down and later we had an office in the same building for a while and used the bar as a canteen…

Rory Gallagher was the greatest but there are some anomalies here:

There is none of rock’s angsty posing. Not true, Gallagher threw some great shapes, took on Berry’s duck walk and wigged out with the best of them.

Image was immaterial to him. Not true. Gallagher’s ever present plaid/check shirt and flowing locks together with his saved from the fire Stratocaster were as branded an image as Slash’s top hat, shades and Les Paul.

Rory Gallagher was one of the greats

Nobody played like Rory. Better than Eric and Peter Green.

You don’t play guitar then…