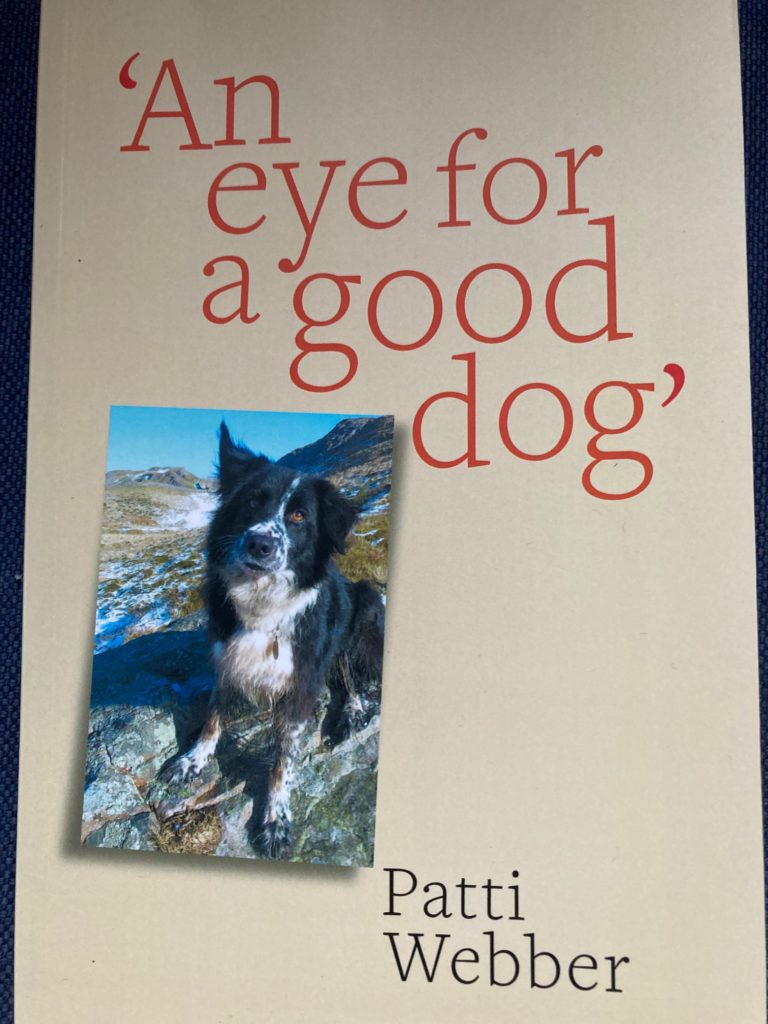

Short story: An eye for a good dog by Patti Webber

Patti Webber

It was sunrise and time to stir. Dafydd opened his eyes to a reddening sky. He looked for early morning stars. After a sleepless night he hauled himself out of bed.

He never idled over breakfast as he readied himself for the daily slog, but today was different. Gripped by sadness, he checked on the sheep and brought in fresh logs. His breakfast, a flitch of bacon, was already sizzling in the pan.

He looked at his father’s hat, bashed over years, which hung from a hook as he moved uneasily in his chair. The hat would cover his tangled hair as he walked and followed each strand of thought.

It was tramping weather. He could saunter over fields and discard things that burrowed into his mind as he fell into the rhythm of walking; the wilder the landscape the better. Four generations of his family had farmed here, and he could lose himself in its ancient feel.

Pain was still fisting its way through his body. Swallowing down his distress, Dafydd said to himself Cadw fynd, keep going. On a familiar path his loping stride made good ground over the trail of corrugated mud his tractor had left. A lone rider had scattered his flock.

He caught a glimpse of a hare sitting on its haunches, its ears like radar before it bolted for cover. It was a day for stretching more than one pair of legs. He drank greedily from the trickle of water which came from the pistyll.

It had been a tough winter; trees twisted and torn in the clamour of bullying winds. A churning mass of clouds carried the threat of snow. He skirted the deep channel of the brook.

Covering scrubby ground and stagnant pools, his walking still hobbled by patches of mud; animal hoof prints had churned up the ground. He had lived alongside the semi-wildness of ponies.

Catching the occasional glint of water as the river Honddu surged in its stony bed he was drawn to thinking of his tussle in waist-high water with many a hard-fighting trout.

A tree where he had last seen a woodpecker at work now spindly and thrashed by the wind. Grey clouds were shouldering one another. He was losing a battle like a ship tossed by stormy seas; full tears like rain rolled down his face.

A stand of conifers lay ahead and the prospect of a steady climb, In the crook of the hills there were still remnants of snow; the cold air was scented with pine. He scrunched his way over dark twigs. The jammed-together trees swayed in a rising wind.

He picked out places where his feet could land safely. Faced with a ruin, all that was left of an abandoned barn, he took cover. It would blunt the edge of the wind-driven rain.

He tucked himself down, cloaked in the smell of bracken, and surrendered to the pain. The wind had abated and blown unwelcome thoughts away. He watched a kite tipping into the wind, eyeing the earth before making its neat kill.

Dafydd’s mother had foraged the hedgerow for plant dyes where nature had taken hold in the nooks and crannies. Chickweed and wild garlic made a tasty salad. Herbs well-washed by rain, and clean as a pin she called little gifts of nature.

He scrambled further up the hill through dense stretches of heather and gorse scrub; charred stubble, a reminder of the last mountain tinderbox. It was unpromising ground.

His heart had settled like the slowing of a runaway horse. A fox, still as a statue, held his gaze before it loped away in a low slink in its constant search for food.

Tiring, his pace had slackened as he followed the worn- down lane and the trail of dry-stone walling he had helped his father build; the age-old way of farming.

An unmade track, a coffin road where the ritual of a coffin being carried by men was still fresh in his mind; a hard but familiar slog.

The spectre of war had passed, his mother’s death followed months later. Her chair remained in position under the stairs where she had taken shelter, stilled by fear.

He gazed at the mountain slopes angling up and remembered the relentless nature and peril of sheep rearing, falling in snowdrifts to rescue buried sheep. When a sheep rejected her lamb at a time when the lambing shed was prepared for new life or lambs were fattened for Autumn sales.

The tireless work of gathering sheep before shearing would bring distant shouts as men and dogs worked together as a team, mindful of the need to keep a full tally.

His badger-faced sheep were grazing among scattered trees; the stone shearing pens and the sty where his last pig had truffled in the mud, or wallowed in it to keep cool.

Crows were gathering and families, like roosting birds, were settled in their homes. He heard the ring of his neighbour’s axe splitting logs and the call of a barn owl like a shiver.

Daylight had dropped behind the hills. Dusk was seeping into the landscape. He watched the moon rising slowly; a time to light the lamps.

He had enjoyed the venture through the squall and made for the near-derelict outhouse where he stored felled logs; well-seasoned ash that gave the fire heart.

There was a movement in the wood pile. In a dark, spidery corner a little owl had hunkered down, its feathers plumped up; its yellow eyes half closed but staring. He lit a lamp and headed for a clearing at the edge of the garden.

A hill farmer, walking the land, Dafydd was often out of doors in fierce weather with few places to shelter.

He had inherited his father’s stubborn streak; his muscles strengthened by pitching manure and wrestling with many a ram, all power and muscle and spoiling for a fight.

He picked up an old spade and, holding a frayed dog collar, he began to dig a tiny grave.

In the auctioneer’s words Shep was a cracking young dog, obedient and easy to handle, a working dog with a proven pedigree.

His reaction to each whistle and voice command had been instant. A live wire, he was expert at navigating the flock. In protecting the sheep, he had struggled, and failed, to escape the clutches of a mangy, stray dog, known for scavenging a scattered flock, starting at their ankles.

Shep had suffered a heart attack. ‘Stay boy. Stand,’ came back to Dafydd.

He imagined the startled sheep, looking foolish and stiff-legged and stamping their feet as Shep gasped for life. The trusted dog who had kept company with him now shrouded in a potato sack; clods of earth were being dusted in snow in an out-of-the-way corner.

In the fleeting light it was hardly a field with a view. His long howl and final whimper were still echoing.

Dafydd had no prospect of handing on knowledge or passing on land, but he had a cloth bag full of money and had an eye for a good dog. His grandfather, a stockman, clung to ‘the old life.’

In a time when they had more land, he had shepherded on horseback. Dafydd would stick to the same breed, a Welsh collie.

Never known to turn a key, Dafydd skirted the crowded beds of herbs and entered the cottage. His sparsely furnished home, where the wind made the chimney whistle, tonight carried the sound of shifting beams.

On the kitchen table, an offering of eggs wrapped in newspaper from Glyn his nearest neighbour.

He tamped down the fire and picked up a brick warming in the fireside oven; wrapped in flannel it would warm his feet in bed. Another hard winter’s day was on the doorstep and he was ravenously hungry, his mind blurred by tiredness.

As he sat by the warmed hearth he craved a pull of beer. The stew had overcooked so instead he had a simple supper of buttered bread and hard cheese. His boots, clogged by mud, were discarded by the fireplace; his feet bore the imprints of his boots.

Memories were being stirred. Using his crook as an extension of his arm, Dafydd had enjoyed working with Shep around the sheep; a dog with pace. As he lay in bed he found himself drifting through the seasons and was soon asleep. Some days are best forgotten.

The next day began with deep snow, it also began with porridge shared with Glyn who was ready ‘to crack on’ and could spare a well-bred dog named Alfie, ‘a good stamp of a dog’ who would keep the sheep going until the next auction.

He was powerful but easy to handle, a dog he could bond with. Dafydd relished the thought of putting him through his paces. Another type of whistle, another manoeuvre from the dog.

As he gazed through the window snow was blanketing Shep in his plot but the world was beginning to turn again.

Patti Webber’s fourth collection of short stories, An Eye for a Good Dog has just been published. It is available to purchase from the author, [email protected].

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.