Short story: The Visitor by Tim Cooke

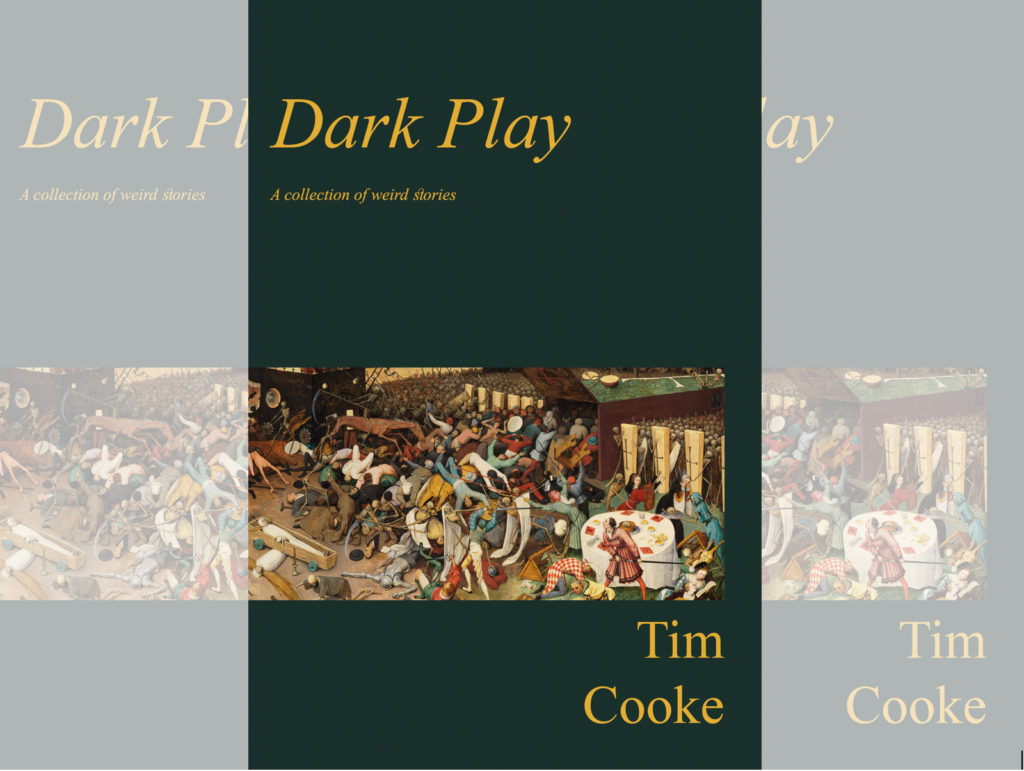

We are pleased to publish a story from Dark Play, being the debut collection of “weird stories” by Bridgend author Tim Cooke.

I put the can of lager down on the bench and took in the view. The woods had turned red in a flash, as if a fire was raging through the valley. There was no sun to speak of, lost behind the grey screen. I took a one-skin joint from my coat pocket and lit up.

Can I eat this, Daddy?

She sat down next to me and dangled an apple in front of us, holding it by the stem. She beamed, proud to have found one that looked edible. It was a healthy green colour, unblemished but for a small brown ring on the lower left-hand side.

Let’s see the back of it, love. She turned it around to reveal a cavern of black rot, as shocking as a head injury. Chuck it, I said.

What? She peered up at me, eyes wide.

Throw it back onto the grass, love—it’s no good.

She flung it down with the others and frowned.

But I’m hungry.

Well it’s lucky I brought this then, isn’t it? I reached into my trouser pocket and pulled out a chocolate bar. Her grin returned, dimpling her flushed cheeks.

Thank you, Daddy.

With the joint tucked in the corner of my mouth, ribbons of smoke curling about my nose, I tore the wrapper apart. I broke the biscuit in half and handed her the first bit, then ate the rest.

Good, isn’t it? I said, washing it down with a sip of lager.

Yep. She paused her chewing, crumbs and chocolate smeared around her lips, and prepared to deliver the line, already anticipating my response. This stuff sure is delicious, she spat, in her best American accent, unable to stop herself from bursting into a fit of laughter. I wrapped my arm around her shoulders and joined in.

After a few seconds of high-pitched hysterics, she stopped and sighed. A gust of wind rolled up the mountain, rippling through the fields, shaking the branches behind us. It was colder now, and the days were getting shorter. We’d spent a fair bit of time in the orchard recently—if this small cluster of trees and the broken picnic bench qualified as such—and had even started calling it our spot. It was only five minutes up the slope from the house, but it was a change of scenery, nonetheless.

What’s that smell, Daddy?

Do you mean my cigarette?

No—it’s a bit like sick.

I sniffed hard, the air sharp in my throat.

Could it be the apples, love? They’re quite pungent, aren’t they?

Maybe—it’s not very nice.

No, I don’t like it much. I looked down at the countless fleshy orbs scattered on the ground, decaying into the damp earth. Do you want to play your game for a bit—I’ll watch?

No thanks. I want another scary story.

I don’t know about that, love—I’m feeling quite tired.

Please, Daddy—I want one about a witch.

I took a final drag of the joint, stubbed it out on the leg of the table and drained the can.

Look at the clouds now—they’re getting dark. I think it’s going to rain.

There was another blast of wind and the trees lunged back and forth.

Please, Daddy, just one story. It doesn’t have to be a long one. She ran her tongue over her baby teeth—unusually small, I’d always thought—searching for further traces of sugar.

Okay, but when I say it’s finished, that’s it, it’s finished.

I know, I promise.

Alright. Come here then. She shuffled closer, cuddling into my coat. You see those woods down there. I pointed at the foot of the mountain opposite.

Yes. Her mouth hung open.

Well, deep in those trees there’s a little cottage—only a wall now really—where an old woman used to live.

A witch?

Yes, sort of—let me explain. This was a long time ago, and there were lots of poor people around here, who didn’t have very much to eat. The woman was very kind and charitable. Do you know what charitable means?

No.

It means giving help to those who need it. She smiled. The old woman was very kind and charitable, so she would make bread, salted meats and things like that, put on her long black cloak and walk over the mountains to share them with people who didn’t have any.

Oh, she was very nice.

She was—she’d even take a big pot with her sometimes, to make soups and stews. She’d cook over an open fire and people would join her and sing songs.

Wow.

But one evening, on her way home from the next valley, a storm set in. It was terrible, incredibly strong, and the rain would not stop—it felt as if someone was throwing stones at her. She tried to shelter beneath a rowan tree, but the swirling winds found her, spinning her round, so that she lost all sense of direction. She struggled aimlessly against the weather, until finally she fell face first into the wet mud.

What’s a rowan tree?

It’s got bright-red berries, like the ones on the banking over there. I pointed at the green lane that bordered the property, beside which a narrow stream flowed. You know—the ones on the other side of the water.

Oh yes, I know.

I loved telling her stories like this. Despite her tender age, she was fascinated by any hint of horror and would hang on my every word. It was easy for me to get carried away, though—especially if I’d had something to smoke—taking cues from the landscape in front of us, letting my imagination run wild. It was a game, really, a kind of play, during which our sense of reality would loosen. For weeks after the first telling, we’d revisit whichever narrative had unfurled from my ramblings, letting it permeate our lives, adding new layers to our isolation.

Now, where was I?

She fell over in the mud.

That’s right, I said, lowering my tone again. She lay flat on the wet ground, too weak to shout or cry, and cursed God for making this happen to her. She swore that she would get her revenge.

What’s revenge?

It’s when you do something back to someone who’s hurt you.

Oh.

Anyway, she stayed there under her cloak for days, not dead but not alive either. The grass, the leaves, the soil and the worms crawled inside her and gave her the strength to rise up to her feet and carry on her journey. But she wasn’t taking food to people anymore—no, she was looking for her home. And do you know what?

What?

She’s still out there now, searching for it—in the woods, by the river, over the mountain trails. Sometimes you can hear her screams on the wind.

Why—is she hurt?

No, she’s frustrated—angry that God could do this to her when all that she’d ever wanted was to be good.

I shifted slightly on the bench to face the valley. The wind had picked up again and the trees were in full swing, a wave of rain barrelling from the east. She leaned into me and shivered.

Did she do any revenge, Daddy?

I’ll tell you later, love. I think we need to go inside now—there’s a real storm coming.

I got to my feet, pulled the last remaining apple from the branch to my left and handed it to her.

Dusk arrived early and the gale continued to crash up and down the mountainside. I lit fires in the hall and the sitting room, and drank another can of lager, while she played happily with her doll’s house. I put some industrial rock music on the stereo and we danced in the kitchen, jumping up and down, howling like a pair of banshees. I made a bowl of tomato pasta for dinner, which we ate at the table, a candle flickering between us. She sipped lemonade, and I moved on to wine.

You were hungry, I said, as she shovelled the last three pieces of penne into her mouth at once.

I like when it’s salty, she replied, licking sauce from her chin.

We sat in silence, the wind shrieking in the dark.

Is that her, Daddy?

She glanced at the window above the sink and then at the french doors, twisting her fingers in a knot.

Is that who?

The witch screaming.

It might be. But you don’t have to worry—I’ll look after you.

She’s got magic, though.

Maybe, but I’m big and strong, aren’t I? And you’re really clever. She won’t get us.

Did she do any revenge, Daddy?

Well, like I was saying, she walks all over these parts looking for her cottage, but she can’t find it. And even if she did, she wouldn’t recognise it—it’s just a ruin now.

I feel sad for her.

Me too, sort of. She does find other houses sometimes, and she feels so jealous of the people living in them—so cross that they have a house and she doesn’t—that she tricks them, so they let her in. And do you know what she does when she’s inside?

She shook her head.

She eats them.

For a second, I thought she was going to cry. Her eyes filled with tears, but then she blinked, smiled and flung her arms around my neck.

Will you definitely look after me, Daddy?

Of course—you’re my girl. And do you promise to look after me?

She nodded hard.

As I held her, the doorbell rang and we both jumped. I felt suddenly disorientated, stranded between two worlds, unsure as to which was real. I gave her arm a squeeze and told her not to worry—the bell was probably broken. To be honest, though, I was excited at the prospect of an intrusion. It rang again, twice this time, and there was no ignoring it.

It’s the witch, Daddy, it’s the witch! She looked terrified. Is it the witch?

I stood for a moment, thinking, then drained my glass.

Maybe, I said. It might be her, but if it is, I’ll look after you, okay? She took my hand and we walked together into the hall, rain still pelting the windows. And you’ll look after me, right?

Yes, Daddy. Her eyes had glazed over and she was white as a sheet.

We stopped in front of the door. I slid the chain across the track and put my finger to my lips.

Let me do the talking, love. And remember—she’ll be in disguise.

I turned the handle and opened it enough to peer through into the porch. Underneath the stone arch stood a young man, perhaps late teens or early twenties, wearing a black waterproof coat and a pair of high-rise walking boots. Mud, leaves and other mulch crawled up his trousers, and he was drenched, strands of sopping-wet hair clinging to his pale face. His jacket rippled noisily in the wind.

I’m so sorry to bother you, he said, executing an overly pained expression. I was hiking on the mountain and got caught in the storm. When I got back to my car, it wouldn’t start—and I’ve got no signal. Would you mind if I used your phone quickly to make a call? I’m very sorry.

It’s no problem, I said, pushing the door closed briefly to unfasten the lock.

Dad! She grabbed hold of the rim of my fleece and shook it, pleading in a whisper, She’s tricking us, Dad—she wants to get inside.

I winked and flashed her a smile.

Don’t worry, love—I’ve got everything under control. I turned back to the man, who was already wiping his feet on the mat. The phone’s just over there on the windowsill, I said. When you’re done, come through and have a hot drink.

I put the kettle on to boil and told her to fetch two cups.

Be careful not to drop them.

She set about the task with a seriousness I’d rarely seen in her, as if much depended on it. The boy was still on the landline, talking quietly to someone I presumed to be a parent—they seemed to be arguing. His manner had changed the second he’d crossed the threshold, as if we were somehow a threat to him. He’d looked nervous, eyes darting about the room, taking everything in. I wondered if, in fact, he was a bit mad.

Here are the cups, Daddy.

I knelt down to her level and spoke softly.

Well done. Now listen—you know more about witches than me, and I need to know how to stop her. What can I do?

She thought.

You should burn witches, Daddy, she said, staring straight at me.

Well, we’re not doing that, love. I paused for a moment. What about poison?

Oh, yes! You could put poison in her drink.

Great idea—you’re a star.

I stood up, dropped a tea bag in each of the cups and poured in the boiling water.

Can you get the milk from the fridge, please? As she slid the litre carton out from the shelf, I picked up the sugar pot and stooped back down in front of her—I lost my balance on the way and had to grab the cupboard handle to stay on my feet.

Are you okay, Daddy?

I’m fine—I think she’s put a spell on me, but I’m alright. I opened the lid. Now look—this is the poison we’re going to use. Can you sprinkle it in? She pinched a small amount between her fingers and held it up, waiting while I took the tea from the counter. I crouched more carefully this time. Put it in—well done. There’s less water in hers, so we won’t get muddled up.

I need a wee, she said.

Go on then, love—I’ll keep an eye on her.

She ran out through the pantry, and I walked into the hall. The boy put the phone down.

Is everything okay? I asked.

Yes. But I’ve got to wait a while. It’s no bother—I can sit in the car.

Don’t be stupid. Come and have a drink, it’s horrible out there.

No, thank you. I don’t want to impose.

I’ve already made some tea.

He sighed, unable to conceal his discomfort.

Okay. He bent down to untie his boot laces.

Do you take sugar?

No thanks.

That’s good—I’ve made one with and one without. I’d have to switch them without her knowing.

Right, great.

I found him a towel from the airing cupboard and led him through to the kitchen, where she was already sitting at the table with a glass of milk, a white moustache above her lip. She’d moved the teas to the edge of the unit.

Take a seat, I said, my words slurring a little now. He sat down opposite her, while I stepped towards the counter, tripping over myself, only just managing to avoid collapse.

Are you okay? he asked, scraping the chair from under him, ready to help.

All good. Just a bit clumsy, that’s all.

I lifted both cups at once, sloshing the hot liquid onto my skin, then put them down on the tabletop—the first, without sugar, in front of him, and the second in my place, next to her. She said nothing. I lumbered into the empty seat, which creaked beneath me, and leaned forward, resting my jaw in my hands. The wind squealed outside, like a trapped animal. The boy blew into his drink and ventured a gulp too soon, grimacing at the heat.

This stuff sure is delicious, she shouted, in her best American accent, and turned to smile at me, beaming from ear to ear. The boy shifted awkwardly. I raised the cup to my lips and drank, too. I’d never had sugar in my tea before. It was sweet and sickly, but also strong, like alcohol, and bitter. I took another sip and swirled it around my mouth—it was grainy and synthetic, so I spat it out. My gums began to burn. I stumbled to my feet, excused myself, and pushed through the pantry to the bathroom. The cabinet below the sink was open, bottles of medicine and pill packets strewn across the floor, multi-surface cleaner and other sprays scattered about the mat. I saw drops of tea on the tiles, and swung around to find her hugging the doorframe, licking at the milk on her face.

What have you done, love?

She waited a few seconds, then spoke.

Sugar isn’t really poison, Daddy, she said, looking down at the ground. But everything in there is.

Jesus Christ. I fell towards the basin and lapped at the cold-water tap, filling my stomach, the ceiling rotating above me, spinning faster and faster, until everything faded to black.

The valley was brighter than it had been, golden shafts spilling through the gaps in the clouds. Most of the trees were bare now, jagged silhouettes stretching into the ether. A train scuttled between the mountains, like a blue centipede. I took the rucksack from below the bench and unzipped it, searching through until I found the apples. I gave her one and bit into the other, juice squirting onto my chin. I unscrewed the flask and poured myself a coffee, watching as she turned the fruit over in her hands, sniffing it.

Do you fancy a walk around the lanes this afternoon, love?

No thanks, Dad. She shook her head from side to side, as if to make herself dizzy. I want another story.

Info and Purchasing

Dark Play by Tim Cooke is published by Salo Press and is available to buy here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.