Spies, lies and Aberystwyth

Meurig W Williams

Goronwy Rees was one of the most brilliant and fascinating men ever produced by Wales, and yet Wales has mostly turned its back on him as if he had never existed. Why is that? Could it be an example of the fear and avoidance of controversy by the Welsh, one of the consequences of colonial oppression identified a decade ago by psychologist Dilys Davies, and which was referred to by Adam Price as characteristic of a defeated nation?

Rees’ life was certainly a quagmire of controversy. As a prize Fellow of All Souls, Oxford in 1928, at the age of 21, he was befriended by many of the academic and literary elite in the Oxford/London circuit, and his company brought delight to so many through his charm, wit, good looks, intelligence and independent thinking, in addition to being a gifted writer.

Two decades later, elevation to bursar of All Souls, followed by the principalship of the University of Wales at Aberystwyth, he was well on the way to becoming a man of considerable stature. So, what went wrong?

It was his friendship with Guy Burgess over a 15 year period, so intimate that Rees named his cat Burgess and made Burgess godfather to one of his sons… the problem being that, during that period, Burgess was an active spy, passing large amounts of sensitive information to the Soviets.

Through the 1930s and 1940s Rees held a range of unrelated jobs, as journalist, novelist, political researcher, Army soldier and officer, corporate administrator, and he married. But he also had affairs with numerous women which caused his wife considerable distress.

1951 was a pivotal year. Rees re-joined All Souls as estates bursar and, following their last drinking session, Burgess suddenly disappeared, together with fellow spy Donald Maclean. It caused Rees considerable anguish. Not only had he lost his closest friend and confidante, but he was now exposed to an element of danger because he did not know the extent to which Burgess could involve him in his now unknown nefarious life.

With the loss of Burgess, Rees felt the need for a different way to continue living on the edge with the element of risk he needed to make him feel alive. That risk awaited him in 1953 at his new position as principal of the university at Aberystwyth.

Bravado

Rees’ first act was to display an element of bravado in an address to the BBC in which he made an onslaught on Welsh culture. He described the Welsh as “extremely orthodox…modes of experience and expression must be approved by the community”. He had a certain “sinking of the heart” that in returning to his own country he was going back to “the land of bondage.” Did that show an element of self-destruction? But his inaugural address soon followed, which was well received. The wisdom of an Oxford don, combined with his worldly experiences, showed through. He delivered a politically safe lecture on the purpose of a university, that it is to train a person to learn how to learn, to ask the right questions and to develop hypotheses.

But his problems were not over. He riled the university establishment with the argument that the limited resources should be used for a broad education rather than the narrow objective of furthering the Welsh language and culture. Yet another problem loomed on the horizon. The kindly university president Thomas Jones who hired Rees was replaced in 1955 by David Hughes Parry who had opposed Rees’ appointment in the first place. He supported the university’s puritanical values and eagerly waited for an opportunity to move against Rees.

Moscow

He did not have to wait too long, for in 1956 Burgess surfaced in Moscow. Rees overreacted to his accumulated stresses by submitting a series of articles to a newspaper describing Burgess as a corrupt man, a spy, a blackmailer, a homosexual and a drunk.

The university authorities then overreacted, held an absurd “trial” which rocked Wales to its core, and released Rees from his job. The university was more concerned with Rees’ association with Burgess’ homosexuality than his espionage, even though Rees was known to be an energetic womaniser.

Questions remain unanswered. Rees himself directs us to some of these. His 1972 book A Chapter of Accidents contains a lengthy and painful prevarication over whether he had believed the confession that Burgess made to him in 1936, at the beginning of their friendship, that he was a Soviet agent. It is unconvincing, the kind of muddled thinking that would have been more believable in Rees’ difficult relationship with his father than between two hard drinking friends. Was that merely a lapse in Rees’ extraordinary degree of intellectual honesty which characterised his writing, or was it more sinister?

Traitor

Historian Hugh Trevor-Roper said that Rees had protected a traitor for 15 years. Noel Annan, intelligence officer and academic, wrote that Rees was “short of a plausible explanation” for protecting Burgess. Richard Crossman, journalist, and politician described A Chapter of Accidents as “an elaborate apologia” for failure to denounce Burgess. Daughter Jenny Rees in 1994 published Looking for Mr Nobody, whose main purpose was to prove Rees innocent of Soviet espionage based on information from KGB files, as if those were known for their veracity. She admitted her confusion over that issue. And Diana Trilling in her incisive introduction to that book wrote that “Goronwy was indeed treacherous for condemning his friend for conduct in which he himself had been engaged.” David Pryce-Jones, author and commentator, wrote that if Rees had shown courage, “he might have forced into the open the whole issue of Communist infiltration in Britain, helping to expose the rot at the top of the country while there was still time to do something about it.”

It was probably that realisation that made it too painful for Rees to admit, at the age of 63, that he was fully aware of Burgess’ betrayal of his country throughout their 15-year friendship. Did that not make Rees equally culpable? Did he fear legal consequences?

In Rees’ 1960 A Bundle of Sensations he described his awareness at an early age of an acute difficulty establishing a sense of personal identity and sought solace for that from philosopher Hume who was aware of that condition. It is now understood that such people seek identity through association with a strong personality. It is my contention that it was Burgess’ dominant personality, extraordinary manipulative charm and Etonian self-confidence, together with brilliance and knowledge that matched his own, and a common need for risk which made them feel alive, and later led to their downfall, that made Burgess so alluring to Rees. On the other hand, Rees provided a more practical reason for Burgess’ interest. It was that, as a young fellow of All Souls, Rees had access to sensitive information that circulated through the heart of the English establishment.

Modern understanding of personality styles provides considerable understanding of Rees’ motivations through his varied and unplanned life. Readers conversant with the details of Rees’ life will recognise the following characteristics, all of which apply to him.

Self-destruction

In the Mercurial style it is intensity of experience that matters, living for the moment with little regard for the future, accepting new cultures and new values, having difficulty with self-identity, uninhibited and undaunted by risk, impulsive sometimes to the point of self-destruction. An Adventurous person has his own outlook on life and the courage to do things his own way, needs to challenge the restrictions and conventional values of society and to resist authority. Uses charm and clever use of language to make friends and make numerous sexual conquests.

Marriage is a possibility so long as he has his freedom. He can be a swashbuckling figure, fun to be around. Lives on the edge, does not fear risk or danger, these being challenges to overcome, for the risk itself can be the reward. Spends money easily, more will turn up from somewhere, so he has a tendency for shortage.

KGB

The extent to which Rees passed information of value to the Soviets is still not known. He was named a spy by a KGB defector in 1999, and it has been claimed that unopened files exist in London which contain sensitive information on Rees. While it is desirable to present the story of a distinguished but fallen Welshman in a favourable light, it is also important to present the facts as objectively as possible.

An admirable description, but limited to Rees’ considerable writing ability, has been provided in 2001 by John Harris in the Writers of Wales series. The Dictionary of Welsh Biography (biography.wales), published by the National Library of Wales dictates that biographies “are not panegyrics, but honest and balanced assessments of the subject’s contribution, recognising weaknesses and failures as well as achievements.”

Regrettably, the biography of Rees, also by John Harris, is in violation of that directive – it avoids most of Rees’ controversies.

Rees was abandoned by his many prominent English friends as a result of his disparagement of Burgess in the newspaper articles, on the basis that he violated E.M. Forster’s dictum that “If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country”, which was a cultural foundation of the English establishment into which he had been accepted. Or did they consider Rees just as much a traitor as Burgess for not exposing him? And perhaps it was more that avoidance of controversy that makes Rees persona non grata in Wales as well.

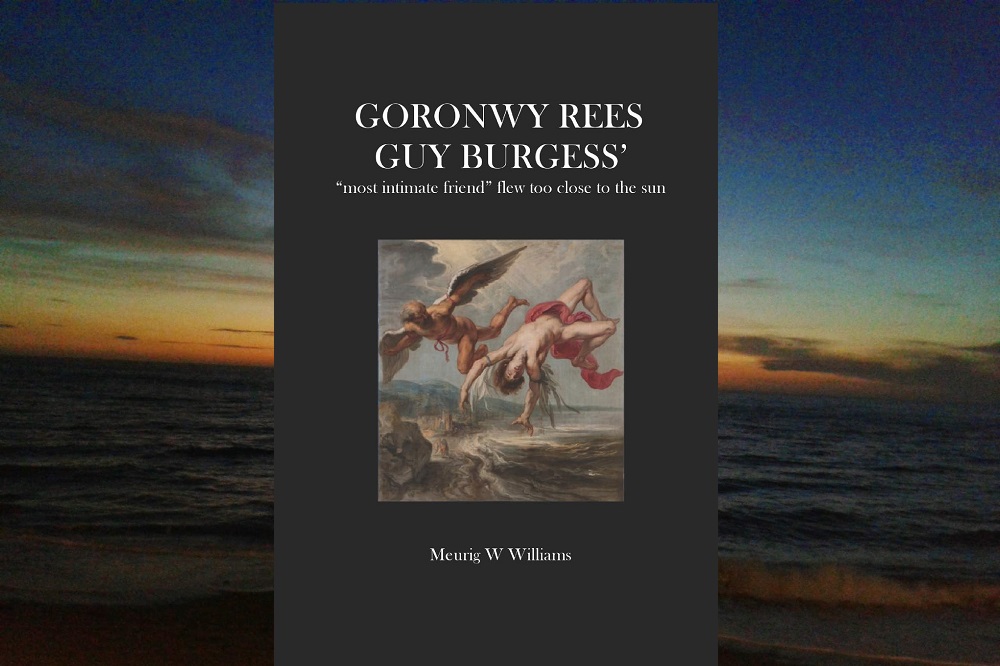

Further analysis of Rees’ life is presented in my 2017 book Goronwy Rees, Guy Burgess’ “most intimate friend” flew too close to the sun.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.