The Bitter Romantic: The poetry of W. J. Gruffydd

Adam Pearce Editor, Llyfrau Melin Bapur

A by-election for a university seat seems an unlikely stage for a battle for the soul of a nation. But this is exactly what happened in Wales in 1943 when Plaid Cymru’s Saunders Lewis stood against the Liberal candidate William John Gruffydd.

Triggered by the death of the sitting Liberal MP, the circumstances of the second world war meant the electorate was small and there were no Tory or Labour candidates.

There was a very real chance that Saunders Lewis would win, a victory that would have been the first election of a Celtic Nationalist MP not from Ireland (the first SNP victory would come two years later).

A strong, popular candidate was needed and the man chosen, W. J. Gruffydd, remains and intriguing character in Welsh history, politics and literature.

Classically Welsh

Born in Bethel, Gwynedd in 1881, his background was in every sense classically Welsh: working class (his father was a quarryman), non-conformist, politically Liberal and, of course, Welsh speaking.

A precocious scholar, Gruffydd won a scholarship to Jesus College Oxford, but before even setting off for university he had become a published poet, with a joint volume written with the older associate R. Silyn Roberts, Telynegion, published in 1900 when Gruffydd was still just 19.

Though some of the poems in Telynegion can now seem rather sentimental, and, dare I say it, emo, in the context of Welsh poetry at the turn of the twentieth century – much of which was pompous, stilted and nebulous – they were perceived as quietly revolutionary for their clarity and (by the standards of their time) daring.

Gruffydd quickly became considered one of the major voices of the first decades of the new century in what frequently referred to as a ‘Renaissance’ in Welsh poetry, alongside others such as T. Gwynn Jones, R. Williams Parry and T. H. Parry-Williams.

He wrote and published precociously through the 1900s, his poetry still in the Romantic vein of Telynegion but showing an increased sophistication and maturity.

An unsuccessful attempt at the National Eisteddfod Crown in 1902 (when he was beaten by his erstwhile collaborator, Silyn) followed by victory in 1909 with his pryddest on Yr Arglwydd Rhys (The Lord Rhys), one of the finest long poems in Welsh to draw on Welsh history.

By 1906 he had been appointed a lecturer in “Celtic” at Cardiff University, where he would stay for the rest of his life, with the exception of the First World War, which he spent in active service in the Royal Navy’s Minesweeper fleet.

This was a very calculated decision which reflected Gruffydd’s ambivalence and internal conflict around the war: despite a natural inclination to pacifism and a deep loathing for the “devilish” conflict, he felt himself unable to stand by and watch others be killed. Minesweeping was unglamorous work whose danger could not be doubted, but which would not ask him to kill others.

Modernism

Though Gruffydd wrote only a few poems about the war they must surely rank amongst the finest poetic responses to the conflict in any language, particularly the bitter 1914-1918: Yr Ieuainc wrth yr Hen, (The Young to the Old), written on Armistace Day, in which the ghosts of those killed in the conflict address the older generation who sent them to their deaths, in a (surely) deliberate echo of Laurence Binyon’s Remembrance day ode:

Mae melltith ar ein gwefus ni

Yn chwerw, ond wedyn cyfyd gwên

Wrth gofio nad awn byth fel chwi

Wrth gofio nad awn byth yn hen.

(A curse sits on our lips

Bitter, but then a smile

To remember we’ll not become like you

To remember we won’t become old.)

The war coincides with a distinct turn in Gruffydd’s poetry away from the Romantic attitude of his earlier work towards a more understated and ambiguous modernism.

Though Gruffydd’s poetic output dried up significantly after 1910, those poems he did write are his best regarded.

Many express a kind of ironic bitterness and whilst it is tempting to attribute this to the war, it was clearly already underway in his poetry by 1909 in poems like Goronwy Owen yn ffarwelio â Phrydain (Goronwy Owen Takes His Leave of Britain), in which the titular 18th-century poet looks back at Wales (which he will never see again) from the ship on which he is emigrating to the US.

Many of his most famous poems portray or adopt the perspective of individual characters in an ironic fashion, like Thomas Morgan yr Ironmonger and Gwladys Rhys, whilst Ynys yr Hud (the Enchanted Isle) reads as a kind of farewell to the Romanticism of his youth.

This shift in Gruffydd’s poetry from the hot-blooded Romantic to the bitter cynic is fascinating, and brings to mind George Carlin’s claim that inside every cynic is a disappointed idealist.

After the war Gruffydd became effectively the head of Welsh at Cardiff, and as an academic and as editor of the journal Y Llenor (the Writer) he made an enormous contribution to the study of Welsh literature.

As a teacher, he deserves significant credit for transforming the way Welsh was studied and taught in the universities.

Under Gruffydd’s leadership Cardiff’s Welsh department was the first in Wales to be referred to as a school of Welsh (as opposed to “Celtic”), the first to lecture in Welsh, and the first to study post-1800 Welsh literature, all innovations later adopted by Bangor and Aberystwyth, and from the start at Swansea when the Welsh department there was established later – and at which Saunders Lewis taught.

Nationalism

Politically, Gruffydd belonged to the old Welsh Liberal tradition, but nevertheless joined Lewis’s new party, Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru in the 1930s; and due to his public profile and general popularity became its vice-president. Although he had bickered with Saunders Lewis over various philosophical and academic issues, often in public on the pages of Y Llenor, he publicly defended him and his associates when they burned down the RAF training camp at Penyberth.

Nevertheless, his vision for the cause of Welsh nationalism – which he believed should remain a primarily cultural rather than political movement, retaining its focus on the language rather than self-government or independence – was at odds with Lewis and others in the party, and by 1940 he had left the party.

He remained a very popular figure in the Welsh language establishment however and it was for this reason, more than his politics, that he was approached by the Liberal party to contest Lewis for the University of Wales seat in 1943 (although Gruffydd campaigned as a liberal and sat as part of the Liberal group once elected, it appears he never actually officially joined the party and was in fact listed as an independent on the ballot).

He jumped at the chance, motivated, according to his biographer T. Robin Chapman, to a significant part by the opportunity to oppose Saunders Lewis.

The ensuing election was bitter and effectively represented a choice between two competing visions of Welshness, particularly in Y Fro Gymraeg: the old Liberal cultural nationalist, and non-conformist vision and the new politically nationalist, secular and European. Gruffydd was frequently accused of betrayal and though he ultimately won the election it was something of a Pyrrhic victory which came at the cost of much of the popularity and good-will he had built up over his long career, and probably did his reputation as a poet no favours.

Of the two today it is undoubtedly Saunders Lewis who holds the greater affection, but with their argument now long confined to the past it is certainly time for a reappraisal of W. J. Gruffydd the man, and particularly the poet.

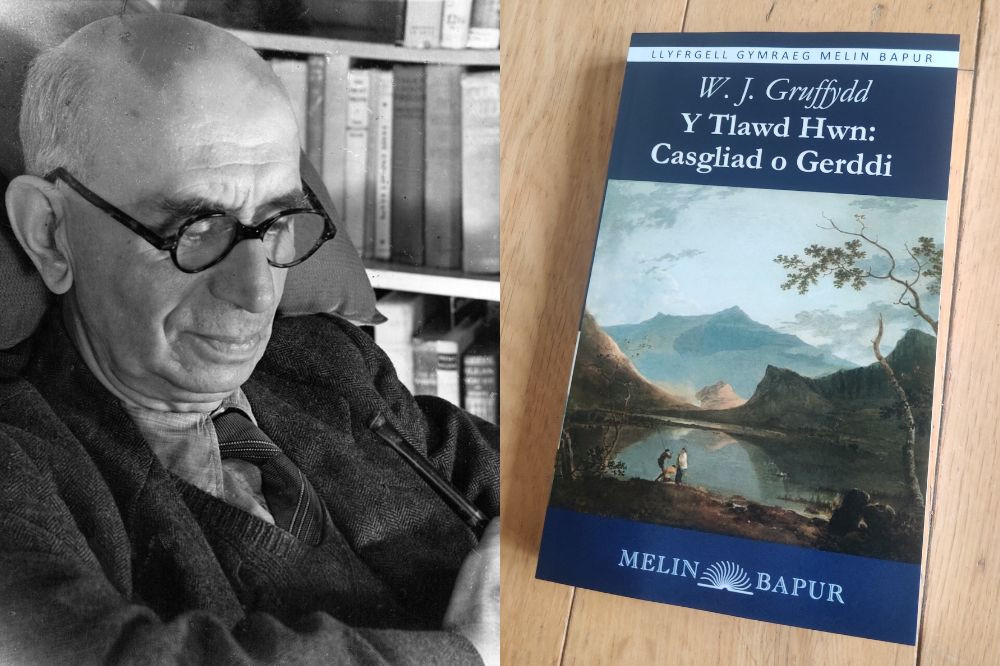

Our new volume, Y Tlawd Hwn: Casgliad o Gerddi is the first volume dedicated to his poetry to be published in 30 years, and the first to collect together the complete published poetry of W. J. Gruffydd, much of which appears in this volume for the first time in over a century and some of which for the first time ever outside a journal or magazine.

Y Tlawd Hwn: Casgliad o Gerddi is available from www.melinbapur.cymru and from all good Welsh bookshops, priced at £9.99+P&P.

Also published this week is Galwad Cthulhu a Straeon Arswyd Eraill, a Welsh translation of the horror stories of H. P. Lovecraft.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Mae’r ychydis ohonnom sydd yn gwybod rhywbeth am >Gruffydd yn barod yn gobeithio Chawson ni ddim.

Yr hyn oeddwn yn golygu ei ddweud oedd ‘yn gobeithio cael barn am y llygfr oeddech yn ei adolygimChawson ni ddim.’

S’mae Arthur – nid adolygiad llyfr mo hwn, dim ond hys-bys i roi gwybod bod y llyfr ar gael. Os hoffech chi adolygu’r llyfr dwi’n sicr y base nation.cymru yn hapus iawn i gyhoeddi eich meddyliau.

Mae W.J. Gruffudd wedi ei gladdu ym mynwent Llanddeiniolen [“Llaniolan”, ys dywedir ar lafar yn y plwyf], Arfon o dan garreg fedd o wenithfaen. Ynghyd a charreg fedd fy Nhaid a’m Nain, mae’r cerrig beddi hyn yn unigryw ymysg gymaint o rai llechi yn y fynwent hon. Yma hefyd mae llwch tair cenhedlaeth o fy nheulu i – o fy hen hen daid ar ochr fy Nhad i fy nhaid. Mae cofeb hefyd i fy hen ewythr, Ellis Williams. Bu hwn yn herwheliwr lleol a chafodd ei ddal gan bobl y sgweiar lleol. Bu’n gaucho ym Mhatagonia am gyfnod, yna’n… Read more »

I am grateful to Adam Pearce for broadening my knowledge of ‘WJG’ as an eminent poet. There is however another side to WJG, a less attractive side. He had a strong interest in mythology, and wanted to (re)create a Welsh pantheon of deities to rival the prestigious Olympiad. He felt he found it in the Mabinogi prose tales. To reclaim its lost divinities he rearranged the characters and plots so drastically that the result was nothing like the original surviving manuscripts. ‘The Mabinogion’ (1912) Rhiannon (1953) In my own description of WJG I take pains to show his passionate nationalism… Read more »

I will defer to others on the quality and nature of Gruffydd’s Mabinogi theories; but isn’t “poisonous paradigm” a bit strong? Even if his arguments were complete nonsense and/or plagiarised.

Da iawn Melin Bapur am ailgyhoeddi cerddi Gruffydd fel hyn. Ddarllenwyr oll, cofiwch ddarllen y rhain hefyd, o wasg Dalen Newtdd: (1) Eira Llynedd ac Ysgrifau Eraill gan W.J. Gruffydd, £15.00. (2) Dramâu W.J. Gruffydd: Beddau’r Proffwydi a Dyrchafiad Arall i Gymro. £8.00. (Y ddwy gyfrol gyda’i gilydd fel ‘Pecyn Llanddeiniolen’am £20.00). (3) Y ddwy stori ‘O’r India Bell’ a ‘Trobwynt’ yn y gyfrol O’r India Bell a Storïau Eraill, gan Glyn Adda.