The Choir: the sound of the valley of song

Continuing our series written by John Geraint, author of ‘The Great Welsh Auntie Novel’, and one of Wales’s most experienced documentary-makers. ‘John On The Rhondda’ is based on John Geraint’s popular Rhondda Radio talks and podcasts.

John Geraint

I’m bound to get into trouble with this article. But here goes…

You can’t beat a good Welsh male voice choir. And amongst good Welsh male voice choirs – and here’s where I’m heading for controversy – it’s hard to beat Treorchy.

Now I can already hear the howls of protest from the Rhondda Fach, from the fans of Pendyrus, and fair enough. No one’s going to deny that there’s more than one Rhondda choir in the Superleague of Welsh Male Ensembles.

But I haven’t said anything that’s factually incorrect. It is hard to beat Treorchy. Back in the days when 20,000 people used to turn out to see who’d carry off the top choir prize at the National Eisteddfod, Treorchy won six times in a row.

They’ve got class, and they’ve got chutzpah, and I’ll put it this way, as carefully as I can: amongst my favourite Rhondda choirs, there’s none ahead of Treorchy.

Welsh cliché

I love choral singing, I do. But, like coalmines and rugby, there have been times when male voice choirs have been in danger of becoming a Welsh cliché.

As the always-insightful Rhondda journalist and broadcaster Carolyn Hitt puts it, ‘For the past 40 years no English television producer has been capable of making a programme mentioning Wales without sticking a pile of old chaps on top of a mountain to croon We’ll Keep A Welcome.’

Well, do you know what? As a former TV producer, I’ve been close to being guilty of something very like that myself – with both Treorchy and Pendyrus.

And I was on location the day that my closest associate in programme-making, the inimitable Phil George, filmed the Treorchy Choir emerging one-by-one from the terraced doorsteps of Dumfries Street (the very street where Phil grew up) to join in glorious harmony, singing Myfanwy in the middle of the road, to the amazement of all the neighbours.

This early manifestation of what’s become known as the ‘flash-mob’ may be a musical cliché, but it’s one that’s been seen and enjoyed by millions. I just checked – quite apart from its BBC broadcast, just one of the many pirated versions of the sequence posted on YouTube has been viewed 404,168 times.

The actor Joanna Lumley has said that “The Treorchy Male Choir’s version of Myfanwy is one of the most glorious things I’ve ever heard in all my long life.” That’s the thing about clichés: they can be popular – and good!

Musical heritage

What makes Treorchy – and other Rhondda choirs – more than a cliché is their ability to reinvent themselves while staying true to their musical heritage.

In Treorchy’s case that heritage was forged by two remarkable men – the choir’s first two conductors, who saw it through nearly half a century of growth and acclaim after it was re-formed in 1946.

Both were schoolmasters, but they had very different personalities and styles. The first, John Haydn Davies, possessed an uncompromising musical discipline which transformed a band of raw and untrained musical recruits into an Eisteddfod-winning institution.

In 1969, he handed the baton to John Cynan Jones, who took Treorchy onto the world stage, touring North America and Australia, singing in the finest concert halls and cathedrals in Britain, recording with EMI, appearing on radio and TV with superstars like Tom Jones, Julie Andrews, Ella Fitzgerald and Burt Bacharach.

Now I wouldn’t claim to know enough about the technicalities of the choral sound to be sure, but a friend of mine who is musical once explained Treorchy’s magic to me like this: it was created by the combination of those first two conductors.

John Haydn gave them the musical foundation, the drilling in tonic sol-fa that produced the precision of their sound. John Cynan built on that, and added an element of showmanship, of show business.

Treorchy pioneered the introduction of the popular hits of the day into the male choir repertoire. By now, they’ve made nearly sixty commercial discs, and they’re probably the most recorded male choir in the world.

I don’t mean to imply, of course, that John Cynan’s musical credentials were anything but impeccable. He was a distinguished church organist in his own right; and at Treorchy Comprehensive, alongside the choir’s long-serving accompanist, Jennifer Jones, he inspired the classical music education of a new generation of Upper Rhondda talent, like the choir’s present conductor, Stewart Roberts.

But any choir which has sung with Shirley Bassey, Ozzy Osbourne and Bon Jovi has been taught how to hit the right notes for the broad popular audience, as well as the musical cognoscenti.

‘The Land Of Song’

Having given you some of the back story of the Treorchy choir, I want to finish by trying to put their sound in a context – a social context. And that allows me to redress the balance a bit. Because there’s no doubt that the foremost chronicler of Welsh choral history is a man who sings with Pendyrus.

Professor Gareth Williams is a distinguished cultural historian, one of the leading interpreters of the industrial and social development of modern Wales.

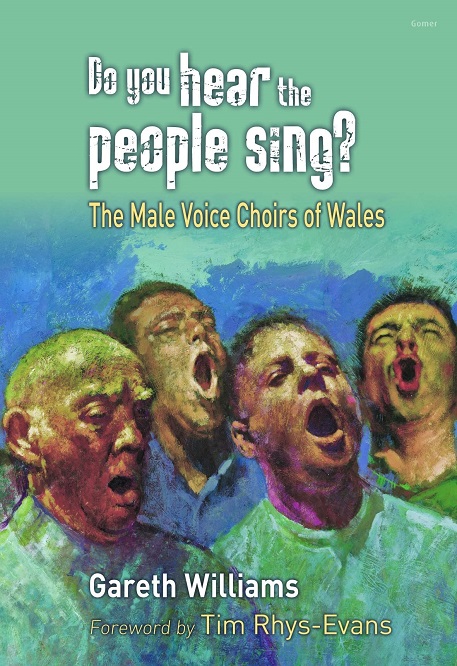

His book, Do You Hear The People Sing? is a treasure trove which traces the origins and growth of choral singing in Wales from the 19th century to the present day.

Gareth Williams brilliantly explains how communities dominated by heavy industry and given a spiritual and musical lifeline by the chapel provided the perfect springboard for a choral revolution.

Wales’ reputation as ‘The Land Of Song’ may have begun with the triumph of the ‘Cor Mawr’, the Great South Wales Choir conducted by Caradog which carried off the One Thousand Guineas Challenge Cup in London’s Crystal Palace in 1872 and 1873.

‘Choral bull-fights’

But it was the scores of male choirs – often linked to the workplace, the colliery, the quarry, the railway, the works, the docks – which established the tradition as a permanent, colourful and dramatic feature of Valleys life.

Crowds followed the choirs in even greater numbers than football teams. Eisteddfod competitions became ‘choral bull-fights’, keenly honed rivalries spilling over into betting, missile throwing, assaults on adjudicators.

Men who did impossibly hard physical jobs, who would struggle to express their emotions in private, felt no embarrassment in standing in front of thousands and singing of love, faith, joy and pain.

‘And the emphasis,’ stresses Professor Williams, ‘as it was in industrial life itself, was on struggle, conflict, and the unity that hopefully would overcome all odds.’ Yes, it was the people’s music. And in many ways, it still is.

In his book, Gareth Williams tells the story of Treorchy as magnanimously as he does that of his own choir, Pendyrus. His conclusion? We should cherish our Male Choirs – all of them – even more enthusiastically than we do.

“They are the frequent object,” he reminds us, “if not of scorn then of cliché, cartooned and caricatured near to death. Except they are far from dead, though their passing has been predicted for the last 60 years…The Welsh male voice choir is alive and well and impervious to cliché.”

All episodes of the ‘John On The Rhondda’ podcast are available here

John Geraint’s debut in fiction, ‘The Great Welsh Auntie Novel’, is available from all good bookshops, or directly from Cambria Books

You can find the rest of John’s writing on Nation.Cymru by following his link on this map

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

I would like Welsh favourites like Myfanwey, to have a verse sung in English, not to exclude us English speaking Welsh people. Please and thank you.