The Price of Coal

Continuing our series written by John Geraint, author of ‘The Great Welsh Auntie Novel’, and one of Wales’s most experienced documentary-makers. ‘John On The Rhondda’ is based on John Geraint’s popular Rhondda Radio talks and podcasts.

John Geraint

It was the minister who told the story. At Mam and Dad’s Golden Wedding Anniversary, if memory serves me right. He gave a little speech at the party, telling everyone about the first time he’d come to the Rhondda, way back in the last century, as a prospective new pastor for Bethel Baptist chapel, Tonypandy.

Dad was one of the deacons, so the nervous young candidate called at our house on Tylacelyn, in the last block at the bottom of the hill, just below Penygraig Rugby Club.

The would-be minister would have climbed the steep steps up from the pavement. Dad would have answered the door, saying, “Welcome, brother!” and testing him out with a firm handshake. And Mam would have insisted that he should have a cup of tea.

But first, smiling proudly, she would have escorted him, as she did with all first-time visitors, to the front room window, so that he could admire the view. To her, it was like gazing on the Promised Land.

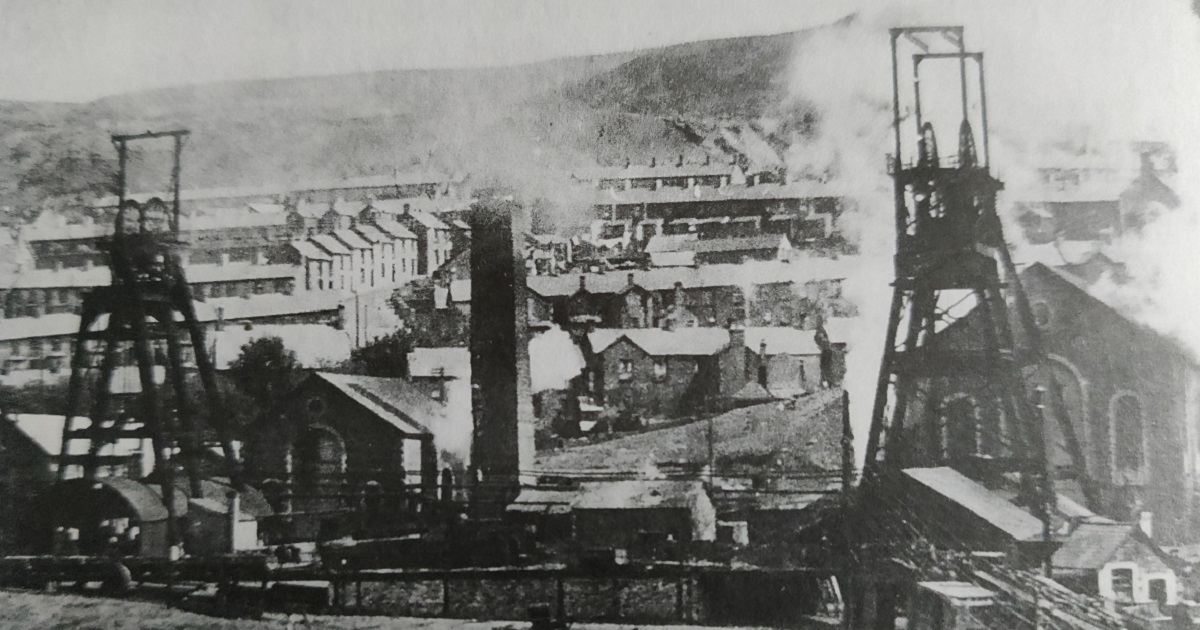

Our house was directly across the road from the old Naval Colliery, but that had been closed the year after I was born. The site had been cleared and partially redeveloped.

In fact, one of my most vivid boyhood memories was standing in a crowd one Sunday morning outside the Rugby Club – the old Colliery Manager’s house – to watch the stack, the colliery chimney, being blown up and falling dramatically to earth.

Mam’s view

So there was the young minister-to-be, looking out of our bay window, at the view, Mam’s view, the one was so proud of.

To the right: Graig Park, the spanking new rugby ground, laid out where the colliery spoil tip once stood. Rising behind it – Craig-yr-Eos, the Nightingale’s Rock. Lovely name! Directly opposite, the mass of Trealaw Mountain, covered in heather.

To its left, below Penrhys, the green flanks of Tyntyla, and glinting in the last of the afternoon sun, long lines of slate roofs leading the eye northward, teasing it with a hint of the cwm opening up again towards Treorchy.

Completing this vast panorama, the sheer slopes of Glyncornel, once bare but adorned now by the Forestry Commission’s upright Scots pines (my Grampa, who’d scarcely been further than Cardiff in his long life, had always delighted in the afforestation: “Duw, it’s just like Switzerland, myn’,” he’d say).

Mam knew that the splendour of all this would impress this pleasant young man. She waited in silence, giving him every chance to drink it all in. There was no need to gild the lily. Finally, she decided the time was right to prompt his appreciative response.

“Beautiful view, isn’t it?” she said.

Genuinely puzzled, he replied, “It’s… a petrol station.”

Lift up mine eyes

He was right, of course. Large as life, dominating the foreground, just yards away directly across the main road, was the Shell Petrol Station. Cars and tarmac, glass and concrete and plastic, pumps and prices and adverts and the Shell logo and all. Built on the site of the little reservoir that served as the old Naval Colliery feeder. Owned and managed by Mr Morgan next door.

It wasn’t that Mam didn’t know all of that or couldn’t see. She could; she simply screened it out in favour of the bigger picture. Perhaps it helped to have a lifelong attachment to that biblical verse, I will lift up mine eyes to the hills.

The minister said later he really didn’t know if she was setting some kind of test for him. His confusion opened my eyes to what I’d taken for granted. For the first time, I realised how telling it was: this filling station on the site of what had been a working mine, where my Grampa had been the colliery blacksmith.

Where once they’d dug coal, now they pumped petrol. From this exact spot had come the black diamond that propelled warships and great ocean liners, and powered massive cargo vessels to the far ends of the earth.

Now the fuel was brought here, to fill up cars for shopping trips, journeys to work, sunny-day outings to ‘beauty spots’: private needs, domestic, local.

King Coal

The world had moved on, the motive force that drove it had changed. What once upon a time the Rhondda had been – the engine-house of modernity – other places, faraway places, were now becoming: Texas, the Persian Gulf, the Oil States of the Middle East. Power had shifted.

That was what the economic crisis of my teenage years in the 1970s was all about. Oil, and the power of oil. That was why there’d been galloping inflation, why the pound had to be devalued, why Britain had to go cap in hand to the IMF, as Rhondda colliers once had had to go to the mine-owners.

It was all here, right in front of me, and I’d never seen it in all the time I was growing up.

King Coal was dead. Oil now ruled. Mam fach, there’d be an Almighty struggle over it one day. The sheikhs and sultans would make sure that the wealth generated by oil stayed in their hands, stayed in their homelands (and why not?!)

What a contrast to the fortunes that came from the coal industry, which had been sucked out of these Valleys, leaving them high and dry.

Modernised

There was another story about our house which the minister didn’t tell, though he’d probably heard it from Mam at some point. It happened a decade before his visit. We were getting the house modernised.

Perhaps something similar happened to your house. The original Edwardian features, the fireplaces, covings and skirting boards were stripped out. Smart white radiators replaced the open coal fires. Artex on the ceilings.

The ‘back kitchen’ – our cosy sitting room with its free-standing stove – was turned into a proper modern kitchenette. The lean-to bathroom, scullery and outdoor toilet were demolished: instead, a square flat-roofed extension was purpose-built to house an up-to-the-minute bathroom suite, matching tub, sink, toilet and all. In avocado, of course.

The wall between the front parlour and middle room was knocked through, with a pair of full-length sliding glass doors between the two to allow for some privacy.

Whilst we were away on holidays, the builders fitted the doors with trendy tulip-patterned glass. The tulips on one door were upside down, but it was too late to do anything about that by the time we got back. Only the cwtsh-under-the-stairs remained as reminder of how old-fashioned it all used to be.

Eye-opener

One Saturday morning before all this building work had begun, Dad and I had gone up through the tiny trapdoor into the attic to measure up, so that we could fill in the form for the Loft Insulation Grant the government was offering.

No-one had been up there for years, decades probably. I went first, up the home-made stepladder my grandfather had put together, poking my head warily into the dark space beneath the eaves.

We’d brought a torch with us. What was revealed in the beam of light was an eye-opener.

Across the whole floor of the attic, from wall to wall, lying there between each rafter, a full six inches deep, there was already a perfectly good form of insulation.

It was pitch black. It was powdery. It was coal dust.

Coal dust

Our house, you see, was less than fifty yards away from the upcast shaft of the Naval Colliery.

The dust had been settling there ever since the house was built. Imagine putting the washing out… or trying to keep the rooms clean every day in an atmosphere like that. Imagine working underground.

That was the price of coal, the real price. Dust. Dust on every surface in the house. Dust on clothes, dust on skin. Dust in the lungs of the colliers. Dust to dust they went, so many of them.

We never did get the government’s insulation put up in our attic. There wasn’t any point, was there? It was all thoroughly draught-proof as it stood. Sealed off by all that settled coal dust.

Mind you, if our house had ever gone on fire, you’d have been able to warm your hands in Blaenrhondda.

‘John On The Rhondda’ is broadcast at about 3.15pm as part of David Arthur’s Wednesday Afternoon Show on Rhondda Radio

All episodes of the ‘John On The Rhondda’ podcast are available here

John Geraint’s debut in fiction, ‘The Great Welsh Auntie Novel’, is available from all good bookshops, or directly from Cambria Books

You can find the rest of John’s writing on Nation.Cymru by following his link on this map

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Wonderful writing.