The story of the iconic Welsh footballer that inspired the stunning Cymru mural

It appeared hours before Wales were due to play Denmark in the last 16 of Euro 2020.

Emblazoned on the side of a building on Quay Street in Cardiff, the stunning mural featuring 22-year-old Nicole Ready wearing a yellow Wales away shirt, was widely praised for its artistic and societal merits.

Part of a project commissioned by Adidas called ‘My Country. My Shirt’, it carried an important message of diversity and inclusivity.

The mural was painted by renowned Welsh street artist Bradley Rmer One and put together by Yusuf Ismail and Shawqi Hasson of Unify Creatives, the pair responsible for the ‘My City, My Shirt’ Cardiff City street art project.

Unify has gained many plaudits for their groundbreaking projects, which use the platform of visual arts and football to spread the message of inclusivity in sport.

What is little known is that Unify was inspired by what many Welsh football fans will tell you is one of the greatest photographs you are ever likely to see of any football player, Welsh or otherwise – Wales defender George Berry resplendent in his Admiral kit.

“It was absolutely that photograph that was the inspiration for the mural of Nicole in a Wales shirt,” says Unify’s Yusuf. “We wanted to showcase people of colour from Wales and that photograph spoke volumes to me.

“A black female with an afro is a very striking image and we wanted to make that the focus of the new mural.”

The photograph of Berry, taken as he lined up to make his international debut in a 2-0 defeat to West Germany on May 2, 1979 in a Euro 1980 qualifier, is iconic for a number of reasons.

Firstly, at the time it was thought that he was the first black footballer to pull on a Wales shirt, some six months after Viv Anderson had become England’s first black international on November 29, 1978.

It has subsequently been discovered that in fact, Eddie Parris, acquired that status some 48 years previously, a fact that had been lost to history for decades.

At the age of 20 the left-winger, then with Second Division side Bradford Park Avenue, made his one and only appearance for the Welsh national team in Belfast on December 5, 1931 when Wales lost 4-0 to Ireland.

This of course in no way detracts from George Berry’s iconography in Welsh sport, a multicultural totem for the era, when racism was rife in the game.

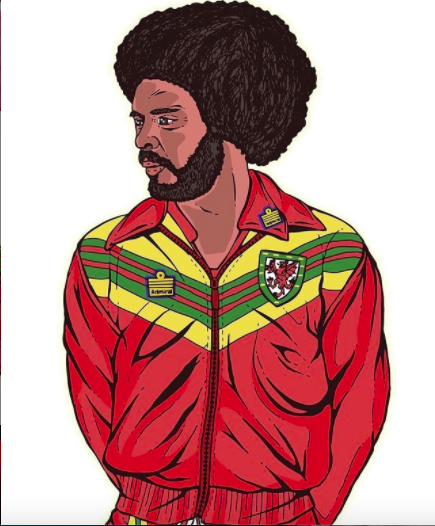

No one could look as effortlessly cool as Berry, in Admiral sportswear, the company that pioneered the replica shirt and who produced what is seen by many fans as the best Welsh shirt of all time.

With its green and yellow stripes and badge centre of chest, the shirt was symbolic of an era when Admiral produced kits which were a kaleidoscope of daring colour combinations and trailblazing ideas.

So iconic is the image of the Wales defender in his Admiral track top it is still influencing stylish football-related clothing all these years later, having been transformed into an illustration on a t-shirt by Spirit of ‘58, the clothing company so closely associated with the Red Wall.

That track top, much in demand from collectors and retro replica kit enthusiasts, had fans in unexpected places.

According to Bert Patrick, the man who founded Admiral, the tracksuit was popularised by Bob Marley in the ‘70s.

Apparently it was a favourite with fans of the reggae superstar because of shades which corresponded with the Rastafarian colours of red, yellow and green. It’s even said that Marley – a keen footballer, who was regularly seen in replica shirts and training tops – wore a Wales track top on British TV, although try as we might we’ve not been able to locate this golden artefact.

George Berry and his Admiral kit certainly had a profound effect on Wales fan and broadcaster Jonny Owen.

“The first kit I had was given to me for Christmas in 1976. It was the famous Admiral top Wales had worn to the quarter-finals of the Euros that year — all red with a V neck and a collar, plus these yellow and green stripes that ran down the shirt and on to the shorts,” recalls Jonny, the documentary filmmaker who directed Don’t Take Me Home, the much loved doc about Wales at Euro 2016.

“It was the 1970s in a football kit — bold and sassy to the point of outrageous. If it had a soundtrack, it would have been disco, with John Travolta running down the wing. In those days, teams kept a kit for years. Indeed, the man I remember most vividly in it was George Berry and he did not play for Wales until 1979.”

Mountain Ash

Berry was born to a Welsh mother and Jamaican father, in Rostrup, Lower Saxony, in West Germany, on November 19, 1957.

Ironic then that he should record the first of the five Welsh caps he earned between 1979-1983 against West Germany. Alongside Darren Barnard, Adam Davies, Alan Neilson and David Phillips, he is one of five Welsh internationals to have been born in Germany.

Berry had a long and distinguished playing career most memorably at Wolves and Stoke City, and had a West Midlands journalist to thank for his international debut. The press man having tipped off the Football Association of Wales about his availability, thanks to his Welsh mam.

In an interview with Stoke City fanzine ‘Duck’ in 2019, he recounted his childhood, part of which was spent in West Germany and Mountain Ash in the Cynon Valley.

“My dad was stationed over there, (West Germany) serving in the British army. I remember as a three or four year old attending kindergarten – I spoke a bit of German but not much. I understand more when others are speaking it.”

Not long after the family upped sticks and moved to the country that would offer him his international opportunity.

“We moved to Mountain Ash in south Wales – near a typical mining community,” he recalled. “At school, the new language issue took some getting used to. My Welsh mother is from a huge family – 1 of 13 brothers/sisters/cousins, so I was looked after down there.

“There was also a sizeable black community in Cardiff, which was new to me and did help in terms of settling in and finding my feet. I felt more in tune there.

“My dad was a massive West Indies cricket fan and all of the Welsh folk down there were big into rugby, so my future football interest would have disappointed them – I think they just thought ‘oh – the poor lad!’

The family subsequently moved to Blackpool, where a young Berry forged his nascent footballing career playing in youth leagues in the area, where he was spotted by a scout from Wolverhampton Wanderers.

It was at Wolves where he received what was to him a shock call-up to the Wales national side when he was believed to be the first black player to turn out for Wales.

“Mike Smith called me up first then Mike England took over,” he remembered. “It was unbelievable for me. I was still a baby at 20, playing for Wolves. I received the letter, I was the first black player to play for Wales, and it was all over the press.

“It’s the biggest accolade you can get because you then become one of the best eleven footballers – and the best in that position – in the country.”

He remembers his debut clearly – a daunting proposition against a dominant West Germany side

“My debut was against West Germany at Wrexham’s Racecourse ground – there were 30,000 there,” he said. “The place was full and we got beat two nil. They were a great team – Karl-Heinz Rummenigge played, amongst others. We would lose 5-1 in the reverse game over there. These were Euro qualifiers – for the 1980 Championships.”

Coming through in the ‘70s and ‘80s, the player with trademark afro who won the League Cup with Wolves in 1980, experienced racism on and off the pitch.

And the taunts were not restricted to the fans waving banana skins and making monkey noises on the terraces.

In the late ’70s and early ’80s racism was also found in the dressing room among white professionals who would try to pass off humiliating jibes as nothing more than friendly banter.

“It was difficult in your own dressing room and even worse on the pitch and then you had the crowds as well,” he recounted in an interview with the Express and Star newspaper.

“All of a sudden when there were four and five black players in the team people realised it [racism] wasn’t good.”

“It was overt,” Berry said of racism during his playing days. “You knew who the racists were because they were in your face.

“Now it’s not acceptable but it doesn’t stop people thinking it. The reality is that football reflects society and there is racism in society, so therefore why wouldn’t there be racism in football?”

The former centre-half also recounted a shocking experience playing away at Millwall when he was spat on.

“If you remember the old Den, you had to walk through the tunnel and all their fans were above it and they had a cage over the top so they couldn’t throw things at you,” he said. “I knew it was coming, so half-time, shirt over my head…I had to change my shirt. It was horrific.

“You talk about the different responses from the black lads – everybody dealt with it differently and at some point you have to draw the line in the sand.

“At that point there is no turning back. The problem I found is that when I confronted it, it was a case of, all of sudden, I’ve got a chip on my shoulder and an attitude problem. It wasn’t a case of ‘it’s wrong’.”

A tough-tackling centre-half, who wore his heart firmly on his sleeve, George Berry is remembered with much love and fondness by supporters of Wolves and Stoke City, where he is something of a cult hero.

Since hanging up his boots in 1995, the former Welsh international has kept himself involved in the game. He gained a business degree and currently works as a commercial director at the Professional Footballers’ Association..

His legacy, however, looms large, nowhere more so than a mural on the side of a building in Cardiff.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Lovely story 😊

Remember him.

Takes me back!

Da iawn, syniad gwych

Great guy …