They also served, but are forgotten

Norena Shopland

Every November the country commemorates Remembrance Sunday to honour the contribution of British and Commonwealth military and civilian people in the two World Wars and later conflicts.

In response to Remembrance Sunday focusing only on veterans and military persons who have died, Armed Forces Day was instigated in 2006 meaning most members of the armed forces can be honoured, even animals have the purple poppy. However, there is a group of people who are forgotten.

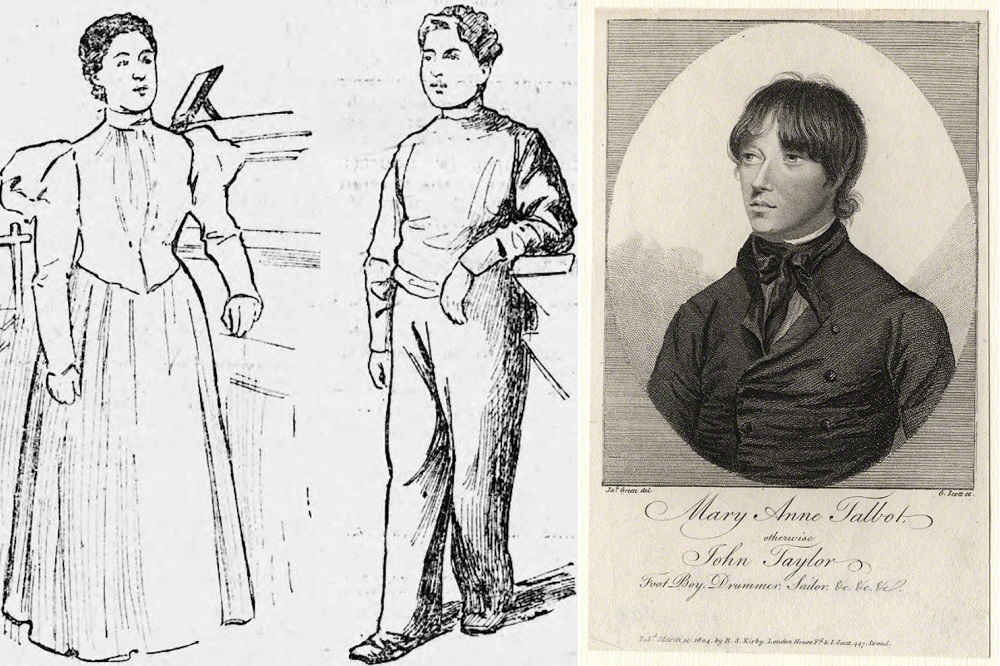

Throughout history, thousands upon thousands or women changed gender and served as men. A whole book could be written about female soldiers who fought and died in the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), and several have been written about those in the American Civil War (1861–1865).

Some became famous such as Mary Anne Talbot, Emilia Plater, Hannah Snell, Phoebe Hassell, Dr Barry and Dr Mary Walker, most however, remain unknown. And those who are known, are seldom commemorated when discussing those who have served.

Reasons women gave for enlisting were varied – escaping domestic violence, fed up with the drudgery of a woman’s life, patriotism, those we might today identify as lesbian or trans, or for love. A Welsh woman tried to join the 43rd regiment not realising her lover was in the 63rd.

Medical checks

Joining the army prior to the First World War was made easier as medical checks were either not carried out or were quite cursory, and by the 1870/80s, women soldiers had become so ubiquitous that long articles on them were beginning to appear.

Many, supportive of the rising women’s independence movements, were generally sympathetic, but most were not. Despite this, few women soldiers were ever censured; instead, they were often used as a stick to shame unpatriotic men.

For those who served long years, sometimes lifetimes, even being lauded for their actions did not necessarily count for much once their service was over. While a number were awarded pensions, most were not on the grounds their enlistment had been illegal.

Throughout the centuries, myriad tales were also told of female sailors, but it was the 1840s that saw a huge proliferation of stories with many carrying very detailed biographical details, more so than any other category of cross-dressing women.

In 1846, the Welshman wrote, ‘two or three years ago there was a great run on female sailors. Every newspaper had its paragraph announcing the discovery of a female sailor. The result was a thorough conviction in the public mind that all sailors were female sailors – that there were no other sailors than female sailors in disguise; and now the curiosity would be the discovery of a male sailor, if such a phenomenon could be well authenticated.’

A. Scott of the Canadian Emigration Agency in Cardiff wrote to the South Wales Echo in 1898 recalling how twenty-five years previously when twenty deserters were caught, seven of them were females. He went to court to watch the trial and ‘no one present could tell for certain which were the females in their sailor rig and white duck pants.’

Challenge

Escaping detection was a continuous challenge and in a ship’s cramped quarters, the women were forced to find unusual and often uncomfortable ways to keep their secret. 16-year-old Amelia Vella from Newport, Wales who served on a commercial vessel in 1898 shared sleeping quarters with five men, explained that she would sit on the forecastle until the men were in their bunks, and then, ‘I would turn in ‘all standing,’ as sailors say; that is, with all my clothes on, and when the foc’s’le lamp was blown out I used to undress quietly in my bunk.’

The longer women served, the easier they could pass as men – or more importantly, as sailors. When Elizabeth Carter appeared in a Newport court in 1859, she was described as walking with the ‘gait peculiar to seamen’ from her ten years at sea.

Susan Brunin of Newport had been at sea for fifteen months, but when she enlisted on a commercial ship in 1855 the captain refused to keep the contract once it was found she was a woman and he informed the police.

They found her ‘gallanting another lass about the town’ and arrested her for being drunk.

The Pembrokeshire Herald mused why she would ‘expose herself to the hardships incidental to a mariner’s life.’ In court Susan explained that nothing whatever would induce her to leave off her ‘fancy attire’ – the bench gave her a harsh lecture on the impropriety of her conduct, and discharged her with some ‘wholesome advice.’

Many of these incredible stories are covered in my book, A History of Women in Men’s Clothes (Pen and Sword, 2021) and so remarkable are some that we should stop making films about superheroes and make them about these women instead.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

What a fascinating article and as you suggest, what great movies these stories would make. True stories with substance. Women finding agency and purpose at the height of the patriarchy. For me, I like the stories of the pirates Ann Bonney and Mary Read, because as pirates, they did not enter the services of kings and lords (and other criminals) and their wars of acquisition. But should the stories of women, lesbians and trans men ever make it into the big screens, I can just imagine the howls of outrage and horror from the internet’s recently invented “gender critical” culture… Read more »