Up The Rhondda! In The Magpie’s Nest

Nation.Cymru is delighted to bring you the first of four extracts from ‘Up The Rhondda!’ by John Geraint, which has been published this week by Y Lolfa.

John Geraint

I was born… in a magpie’s nest. Yes, you read that right: a magpie’s nest. It’s a strange thing to say, I know. But it’s the truth. Chances are, if you’re roughly the same dap as me (as we say in the Valleys for people of a similar age) and you grew up in the Rhondda, you were born in a magpie’s nest too.

I’m quite proud of the fact, to be honest. I mean, it’s got more polish to it, a bit more graen than saying you were born in a workhouse. Though, now I come to think about it, it’s sort of true that I was born in a workhouse…

Am I speaking in riddles again? Fair enough. Give me a moment and I’ll explain.

I had to fill in a form this morning. One of those online things. And there it was, an empty box: Place of Birth… I’m always scrupulously honest on these forms, and though I think of myself as a Penygraig boy, through and through, born and bred, I’m not really.

My actual entry into this world, like almost all the other Rhondda children of my generation was in… Llwynypia. That’s what it says on my birth certificate, so it must be true.

It’s there on my passport too: Place of birth/Lieu de naissance: Llwynypia.

It’s a great thing to have on a passport or any official document. Because if any officious official starts questioning you, and they come from anywhere beyond Offa’s Dyke, they look at the word ‘Llwynypia’ and more or less give up before they’ve found what they think is the first vowel.

Llwynypia. Llwyn-y-pia. Llwyn is literally a bush in Welsh, but when a bird’s name is mentioned next to it – in this case pia, a magpie – then you can take llwyn to mean ‘nest’. Llwyn-y-pia – the magpie’s nest.

And, of course, the reason that I – like so many other Rhondda people – was born ‘in the magpie’s nest’, is because Llwynypia Hospital was, for many years, the maternity hospital for the whole valley.

The workhouse

But where does the workhouse come into it?

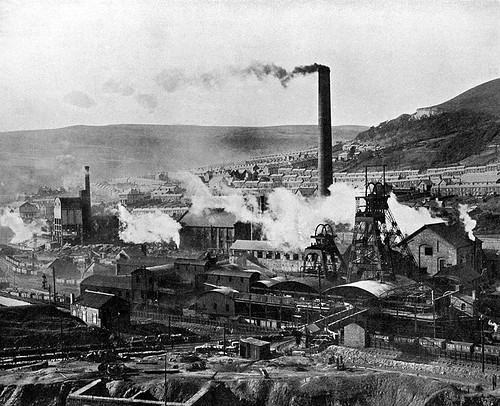

The Rhondda’s coalmines first opened up when Queen Victoria was on the throne. There was no such thing as the welfare state. If people couldn’t work – because they were ill, injured, or simply old – and their family couldn’t support them, they had to turn to the Parish for assistance.

Often, they were sent to the dreaded workhouse.

It was a harsh system, infamous for forced child labour, malnutrition, beatings and neglect. Put simply, the combination of punishing workload and poor diet killed many of the inmates.

It was Charles Dickens who helped to open the eyes of the Victorian public to the evils of the workhouse, in his novel Oliver Twist. Dickens describes how children were mistreated and underfed, with poor Oliver uttering the immortal request: “Please, sir, I want some more.”

More enlightened

The first workhouse anywhere near the Rhondda opened on the Graig in Pontypridd in 1865. By the end of that century, with the inrush of people to the coalfield, it was far too small to cope with the need. So the Board of Guardians bought 25 acres of land at Llwynypia to build a new workhouse. It was opened in 1903.

Accommodation, behaviour and diet there were subject to the usual strict discipline, but social norms in the new century were somewhat more enlightened than in Dickens’s heyday, and the new institution was described as ‘a home for the destitute, chronic sick and elderly’.

Able-bodied inmates were put to work in the kitchen, the laundry or on the smallholding on the site, tending fruit and veg and cereals. Chickens, goats and pigs were kept there too, and they needed looking after as well. They may indeed have been treated better than the human residents.

It wasn’t until 1927 that the workhouse became a proper hospital. The inmates were moved out, though one of them – a Mr Chris Jordan – was given a hospital bed, and he stayed on there at Llwynypia for decade after decade, until he died, as astonishingly recently as 1986.

Meanwhile, it took some time for Rhondda people to get used to the idea that what had been a Poor Law Infirmary was now treating general patients, not just the destitute.

Gradually, the facilities were upgraded – with an operating theatre, a pathology lab and a Radiology (X-ray) department.

Maternity facilities

In 1930, Glamorgan County Council took over the hospital from the Board of Guardians, and this is when maternity facilities were properly introduced, so that the hospital could be recognised as a training school by the Central Midwives Board.

During the Second World War, part of the hospital was dedicated to the treatment of wounded servicemen, so Maternity was moved out again, across the valley to Glyncornel House, which was acquired from the Powell Duffryn coal combine for the purpose.

After the war, on 5 July 1948, the National Health Service was ‘born’. Llwynypia Hospital got a new lease of life. Facilities were upgraded.

In the 1950s, Casualty and Physiotherapy departments opened, together with a new, modern Maternity unit. And this is where I come in – just about!

Panicked

My Mam was 30 when I was born – quite old for a first-time mother in those days. My parents weren’t so fortunate as to own such a thing as a motorcar; so our neighbour next-door-but-one on Tylacelyn Road kindly agreed to take my mother the couple of miles up to the hospital in his car when the time came.

Maldwyn Jones was a responsible businessman – he owned a printing company in Tonypandy – but he and his wife Elsie didn’t have children of their own, and I think he must have been slightly panicked when my mother knocked at the door, already in labour.

Fathers didn’t usually attend births back then. So it was just Mam-to-be and Maldwyn speeding through ’Pandy in the car; and me, baby John, ready to appear on the scene at any moment. But, when he got to Glyncornel Lake, panicked Maldwyn turned left.

He was zooming up through the woods to Glyncornel House before my mother – who was understandably distracted by other matters – realised his mistake. Maldwyn was taking her to the old Maternity unit. But that was now a Geriatric ward.

Some children are born old, so they say, but I wasn’t ready to join the elderly chronic sick on day one! Thankfully, Maldwyn managed to turn the car around and get Mam to Llwynypia, just in time for me to make my grand entrance.

I’ve got a black-and-white photo taken on the maternity ward to prove it – three medical staff in starched aprons holding me and two other bonny Rhondda newborns up for the camera.

I wonder where those other two babies are now – if you were born in Llwynypia in the second week of July 1957, please get in touch and let me know.

Protest

Fast forward to my teenage years, and Llwynypia Hospital features for another reason: the first protest march I ever went on.

It was impressive, mind – thousands demonstrating against the closure of the Casualty Unit at Llwynypia, the only facility like it in the Rhondda, and the centralising of emergency services far away at the East Glamorgan Hospital in Church Village, beyond Pontypridd.

On a sunny afternoon, we paraded from the hospital gates on Partridge Square, down through ’Pandy and on to a public meeting in the famous Judge’s Hall, where many rallies and political debates had been held over the years.

Down through Dunraven Street we marched: nurses and miners, doctors and housewives, schoolchildren like myself, carrying banners, chanting… and singing, to the tune of ‘Tipperary’:

It’s a long way to East Glamorgan, it’s a long way to go.

It’s a long way to East Glamorgan, and the roads are awful slow.

Goodbye Llwynypia, farewell Partridge Square,

It’s a long, long way to East Glamorgan –

You’re dead ’fore you’re there.

Those words, from the early 1970s, have stuck in my mind for half a century: such a pointed and clever adaptation. I’ve always wondered who thought them up, and how all of us marchers got to learn them.

A glorious cause

It was a glorious cause. But a total failure.

The ‘rationalisation’ went ahead anyway. All that was left for in-patients at Llwynypia in its last years were the bookends of life – the Geriatric wing, and that famous Maternity unit. Even that went in the end.

Now, of course, the buildings are gone too. There’s a spanking new hospital, Ysbyty Cwm Rhondda, not far from Partridge Square.

But for me, and I guess for thousands of other Rhondda people who began life there too, it will always be that old institution up on the hill that will be dear to the heart.

I may have been born in a magpie’s nest, one that used to be a workhouse, and nearly, nearly on a geriatric ward. But thanks to Llwynypia Hospital, I can say it proudly: I’m a Rhondda boy.

‘Up The Rhondda!’ by John Geraint is published by Y Lolfa at £9.99. It’s available from any good bookshop, or directly from Y Lolfa.

John Geraint is one of Wales’s most experienced documentary film-makers. His acclaimed debut in fiction,The Great Welsh Auntie Novel, was published in 2022. In this new book based on his popular John On The Rhondda podcasts, John Geraint fixes – with a film-maker’s eye – the experience of life in this vibrant, globally-renowned mining community.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.