Wales, the Welsh, and Shakespeare

Desmond Clifford

Little is on offer in Wales to mark the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s first folio, and this is a pity. Shakespeare is England’s icon, of course, but he is also a universal figure and should be celebrated here.

In fact, Wales features a fair amount in Shakespeare. There’s Glendower, of course, in Henry IV Part 1, Captain Fluellen in Henry V and Sir Hugh Evans, “a Welsh parson”, in that shameless money-spinner, The Merry Wives of Windsor. Cymbeline is set in pre-Roman Britain – Wales before it was called Wales – and Milford is specifically name-checked in the action. Lear has long disappeared as an English Christian name but survives in contemporary Welsh as Llyr.

There’s no evidence that Shakespeare set foot in Wales, but none that he didn’t either. His patron, to whom the first folio is dedicated, was the Earl Pembroke so the thought is at least plausible.

There is little that ties Shakespeare to time and space beyond some basic dates and this a source of benefit rather than frustration.

Like his creation Ariel, Shakespeare seems to hover in a netherworld of fantasy and imprecision between what’s real and invented. It is precisely this amorphous quality which enables us to paint onto Shakespeare what we will, just as you like it.

Glendower

His greatest Welsh creation was Owen Glendower (Shakespeare’s spelling), the show-stealing supporting role in Henry IV, Part 1. Shakespeare’s Glendower is boastful, vain and pompous:

“ ….at my birth

The front of heaven was full of fiery shapes,

The goats ran from the mountains, and the herds

Were strangely clamorous to the frighted fields.”

These are scarcely attractive qualities but form a satisfying counter to the uncritical lionisation sometimes attributed to Glyndŵr as he sought to align his personal interests with those of the nation.

The historical Glyndŵr was what we would now call an oligarch, as much Roman Abramovich as El Cid. To be fair, he was battling the usurper Prince of Wales and the mighty forces of the crown ranged around him; a little whistling in the dark seems reasonable.

Glendower is a brilliant character and in any decent production capable of surmounting his cameo status to print a lasting impact.

He is aggressively aware of his consequence, as any rebel fighter must be. His verbal dexterity and silky charm run rings around the pellet-headed Hotspur and the plodding Mortimer, to whom Glendower’s daughter is married.

Glendower is cultured and has his daughter sing to change the atmosphere. You feel like you could listen to Glendower all day:

“And on your eyelids crown the god of sleep,

Charming your blood with pleasing heaviness,

Making such a difference ‘twixt wake and sleep

As is the difference betwixt day and night,

The hour before the heavenly-harnessed team

Begins his golden progress in the east.”

When I read Shakespeare’s Glendower I think, for example, of the penetrating fluency of Cerys Matthews or Michael Sheen or Gwyn Alf Williams. A stereo-type perhaps, but surely Shakespeare was onto something.

In any case, Hotspur and Mortimer proved unreliable allies, leading to that home-grown historical document the Pennal Letter. This was penned in Latin by the historical Glyndŵr in the village of Pennal on the road between Aberystwyth and Machynlleth.

The letter appealed to the King of France to join in alliance with Wales against the English crown: “my nation, for many years now elapsed, has been oppressed bythe fury of the barbarous Saxons”.

His letter was delivered into the King’s hands by the clerical civil servant Gruffudd Yonge and is preserved at the French National Archives in Paris.

Icons

Glyndŵr and Shakespeare have things in common. Both are icons in their worlds, albeit the whole world in Shakespeare’s case. For both, scholars can assemble biographies (let’s salute the late RR Davies, the pre-eminent Glyndŵr scholar of our age) which somehow reflect less than the sum of their parts.

Shakespeare is infinitely bendable because we know so little about him and his views. His characters mouth opinions on everything under the sun, and we feel the relevance of his words all these centuries later.

But what did Shakespeare really think? No one has a clue. I see him on The Graham Norton Show blushing, uncomfortable in the limelight and tongue-tied.

Some of this same sense of mystery hangs around Glyndŵr. We don’t know what he looked like. We know little of what he believed beyond some thoughts on higher education and church policy.

We don’t really know to what extent he was a true patriot or a self-serving charlatan. Good. For exactly these reasons, he is what you want him to be (I suspect he was an untidy and compromised mixture of the elevated and selfish).

Glyndŵr’s death was never recorded. He just slid out of recorded history, like the Fool in Act 3 of King Lear. Glyndŵr took office in that other realm, the one that never dims, where victory remains elusive but where defeat is never final, peering over the shoulders of the living and brandishing chimerical standards of lions rampant.

You sense his hand daubing messages on rocks and bridges of rural Wales, and an aching clarion in the forest dying into the crow’s screech.

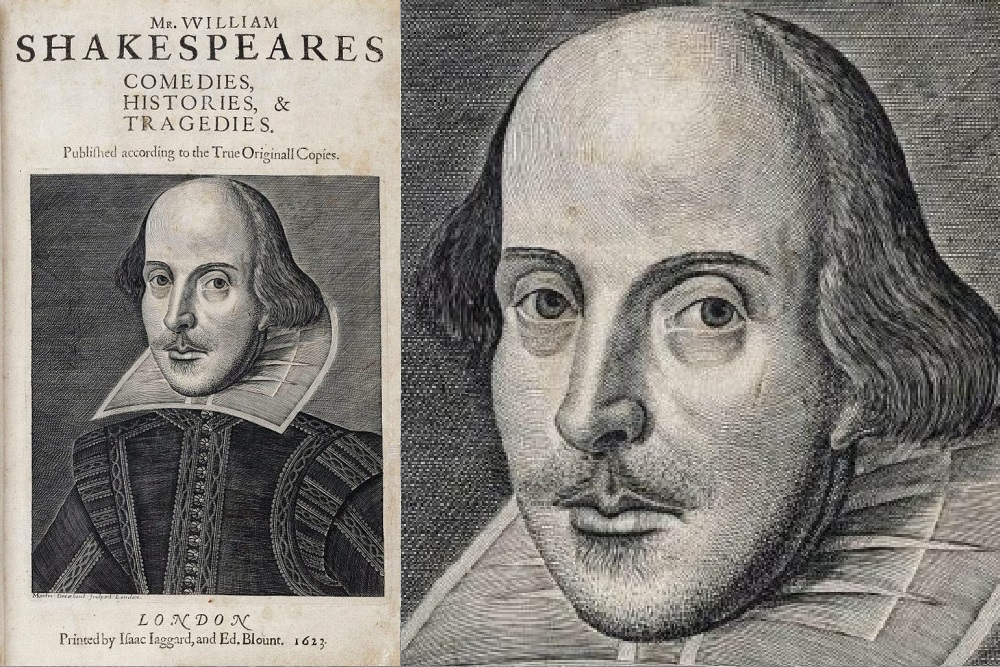

First folio

So far as is known, no copy of Shakespeare’s first folio rests in Wales. A copy was owned by Charles Watkin Williams Wynn of Denbigh but after his death records show it was sold to one James Beaufoy in 1851.

The most recently discovered folio was found in 2016 at the ancestral home of the Marquis of Bute, on the eponymous isle in Scotland.

There’s no reason to believe they ever brought it to Cardiff but, at this cosy time of year, I like to conjure an image of the third Marquess settling down in front of a log fire in his newly decorated lounge at Cardiff Castle to read out loud from Henry IV part one.

Some 750 copies of the first folio were printed in 1623, of which 235 are known to be extant. The largest share, 82 of them, are housed at the Folger Institute in Washington D.C.

Folger was a magnate who left his fortune to build a neo-classical temple to Shakespeare, striking from the outside but actually rather gloomy inside.

The Folger Institute has the means to buy up any copies available on the open market. The next largest owner is Meisi University, Tokyo which has 12. New York Public Library owns 6.

Nearer home, the British Library owns 5 copies while Oxford and Cambridge universities own 4 each. Birmingham City Library has one all of its own, aptly enough as the metropolis closest to Stratford.

Thrilling

It’s sad that there isn’t a copy in Wales; and here is my modest proposal. Couldn’t the British Library, from its collection of 5, place a permanent loan copy at suitable locations in each of Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland?

This would still leave two copies in London and would constitute a generous act of cultural partnership, marking Shakespeare’s universality among the union nations. We might lend them some Dafydd ap Gwilym in return?

Alternatively, if there’s a budding Welsh plutocrat with an appetite for philanthropy and £10m to spare, that should get us one.

Better still, we could ask the French to loan us the Pennal letter again – it’s 25 years since it was last at the National Library. Shakespeare’s Glendower and Glyndŵr’s letter side by side.

What a thrilling exhibition that would be. The contemporary document signed by Glyndŵr himself: “Vester ad vota, Owynus pincips Wallie/ yours avowedly, Owen, Prince of Wales”. And the first text of Henry IV part one, the imaginative vision conceived for the metropolitan audience:

“These signs have marked me extraordinary,

And all the courses of my life do show

I am not in the roll of common men.”

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

El Cid was another self serving politician,who like Glyndwr has become legendary,Roman Abramovich is just a shady businessman.

It is generally accepted among scholars that a lot of work is ” attributed ” to Shakespeare, Steven Fry in a TV show highlighted the anomalies and some have offered plausible names for authors of these works. There is no record of him attending ” his school” but there are parish records of children born at the time registered at the school. Documents show his signature as a X, and handwriting experts say that several different people signed documents as Shakespeare and there are several different spellings on said documents, so why would we celebrate him, when we have our… Read more »

Pennal letter?

BTW Pennal is a village between Machynlleth and Aberdyfi, not Aberystwyth.

Indeed. I wondered about a Penal letter, penned – possibly – in jail. I cycled through Pennal and was disappointed, though not surprised, at the lack of any sense of its history.

The house it was written in was restored and there is a copy of the letter in the house in Pennal. The owner died and I think it is closed at the moment. It is on the site of the Roman camp and was open for years with the owner giving private tours.

The American author Henry James wrote: I am haunted by the conviction that the divine William is the biggest and most interesting fraud ever practiced upon a patient people.” The plays were court plays written by several unnamed courtiers for performances at the Elizabethan court and houses of the aristocracy at a time when writing risked the severe punishments applied to heresy, blasphemy and treason. The name of a William Shakespeare was added to the Portfolio of plays at a later date when the authors were dead. Almost nothing is known about the so-called Bard, jobbing actor and money-lender. When… Read more »

When I was in the sixth form, I read an interesting book called ‘The Welsh in Shakespeare’ in which the author pointed out that the Bard was friendly with the Welsh community in Stratford-on-Avon and incorporated some of what he learned from them into his plays.

Including the post-Norman Viking settlement of Milford in pre-Roman Cymbeline?

Sir Henry Salisbury of Llyweni, Dyffryn Clwyd, must have owned a copy of the First Folio as he penned a poem to congratulate its compilers. John Hemings and Henry Condell in 1623. However, sadly, Salisbury’s interest in Shakespeare was an indication of the rapidly increasing anglicization of the Welsh gentry at this time: Salisbury’s ancestors had been among the leading patrons of Welsh language poetry, but Salisbury patronage of the bards petered out with Sir Henry’s generation. This is a lively article, but its perspective is somewhat anglocentric. And its depiction of Glyndwr as a fifteenth century equivalent of a… Read more »