Watts in a name – exploring the place names of Rhondda

Continuing our autumn series by John Geraint, author of ‘The Great Welsh Auntie Novel’, and one of Wales’s most experienced documentary-makers. ‘John On The Rhondda’ is based on John Geraint’s popular Rhondda Radio talks and podcasts.

John Geraint

When you were small, did you ever write out your full, full address? You know, the complete address that located you precisely as a small child in a vast cosmos, in case an alien spaceship was looking to deliver a parcel to you, a long list of places starting with your name and the number of your house and your street and ending something like ‘Europe, The World, The Solar System, The Milky Way, The Universe’.

I remember doing that, and I’ve got a vague memory too of asking my grandfather who lived with us, and spoke Welsh, to translate our address into English – I was worried those aliens would struggle with the Welsh placenames.

Apparently, our house was on Hollyhill Road, Rocktop, Fullingmill Meadow, Babblingbrook Vale. Sounds awfully posh, doesn’t it? Like somewhere in Surrey, or up in the Yorkshire Dales. The proper Rhondda version’s a bit different. ‘Hollyhill Road’ – that’s Tylacelyn. ‘Rocktop’ is Penygraig, of course. ‘Fullingmill Meadow’, believe it or not, is Tonypandy. And ‘Babblingbrook Vale’ – well, we’ll come to that.

Tre

Local place-names and their meanings have always fascinated me. I was talking to someone the other day about all those Rhondda ones that start with ‘Tre…’ – Treherbert, Treorchy, Trealaw, Trehafod, Trebanog. It led me on to thinking about why they were called what they were called, and about lots of other places too.

‘Tre’ or ‘tref’ means town in Welsh. So Treherbert is Herbert’s town. Herbert was one of the family names of the Marquess of Bute, the lucky so-and-so who happened to own the land where they discovered the world’s best steam coal in 1855. Up until then, the area was known as Cwm Saerbren.

We used to call someone who was lacked common sense ‘a bit of a Herbert.’ I’m not sure if there’s any connection with the Butes, but however bright or otherwise they were, they certainly got rich from what other people dug out from underneath Treherbert.

Treorchy takes its name from the stream that flows from the mountain down into the River Rhondda there – the Gorchi or Gorchwy originally. It gave its name to the Abergorki Colliery, and so to ‘Tre-orci’ with the ‘g’ disappearing in one of those mutations that trip up so many of us as we try to learn Welsh.

Trealaw – now, that’s got a nice story behind it. ‘Alaw’ was the bardic name of David Williams, another man who made a lot of money from coal. He bought up the land in Trealaw with the proceeds. He was a proud Welshman – very big in the Eisteddfod.

There’s a statue of his son, Judge Gwilym Williams, of Miskin Manor, outside the Law Courts down in Cardiff, not that I’m suggesting you’ve got any reason to go that way.

Hendre

Trehafod takes its name from a farm. The ‘hafod’ was the upland farm, where cattle and sheep were taken to graze in summer (‘haf’ in Welsh) – as opposed to the ‘hendre’, the old ancestral winter home down in the valley.

‘Hendre’ crops up in local placenames like Hendrecafn, Hendreforgan and Hendregwilym. Hendregwilym was translated into English as Willamstown, which caused a bit of a stir at the time. I’m not sure if the same thing happened when Glyn Rhedynog became Ferndale, but another Welsh coalowner, David Davis of Blaengwawr, seems to have been behind that.

Tylorstown and Wattstown, on the other hand are named after English coalowners, Alfred Tylor of Newgate in London, who bought the mineral rights to Pendyrus Farm in 1872; and Edmund Hannay Watts of Messrs. Watts, Watts and Company. So perhaps they should have called it Wattswattstown!

Stanleytown is named after a pub, the Stanley Hotel, though who the pub is named after – well, that’s another matter.

As for Trebanog, ‘bannog’ means high up or lofty. In Welsh, the Brecon Beacons are Bannau Brycheiniog – it’s same word, ‘ban’, a pinnacle. High up, lofty… I bet whoever named Trebanog approached it by struggling up Cymmer Hill.

Gelli

There’s a whole bunch of Rhondda placenames which are simple enough to understand if you know a bit of Welsh: Pentre – ‘village’; Dinas – ‘city’ or ‘hill-fort’; Ystrad – ‘a vale’, the flat floor of a valley.

Gelli is ‘a grove or copse of trees’.

There were two farms in Gelli, Gelligaled and Gellidawel: ‘hard copse’ and ‘quiet copse’, which sounds a bit like the formula for a long-running police drama series.

Tynewydd is ‘new house’; Ynyshir, ‘long island’, like in New York, though I never heard of a cocktail called Ynyshir Tea. In fact, as we’re a fair step from the sea, ‘ynys’ here, and in other Rhondda places like Ynysfeio and Ynyscynon, just means land by the river. So Ynyswen is ‘white riverside’.

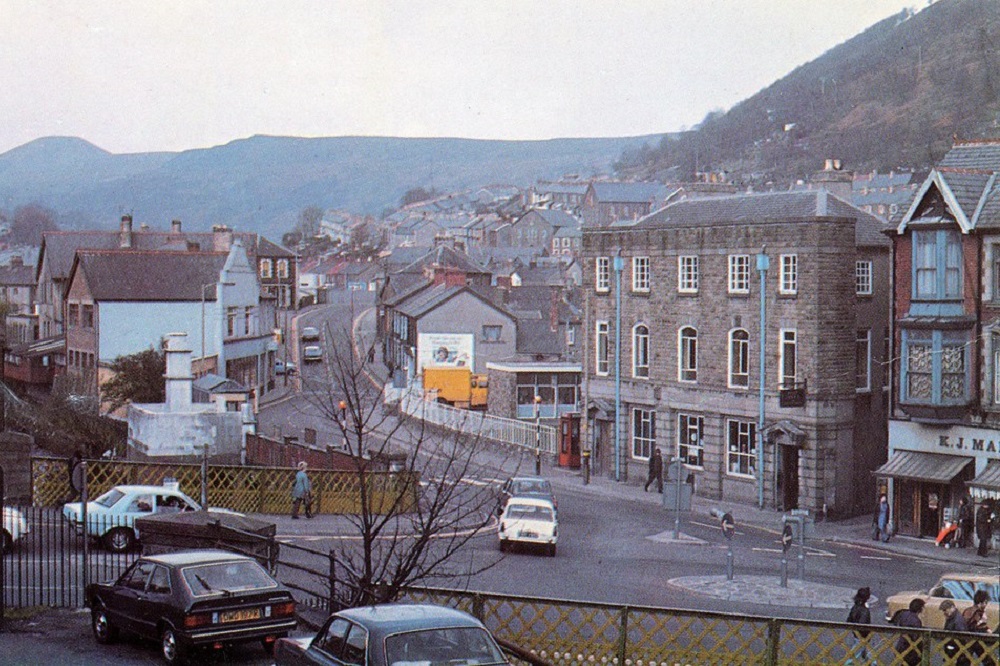

Porth – Y Porth – is ‘the gateway’, which is what it is – to the Rhondda Fawr and the Rhondda Fach; and Cymmer – the Welsh word cymer (‘confluence’) – is the spot where the two rivers meet.

Maerdy is ‘maer-dy’, the mayor’s house: in the Middle Ages, the ‘mayor’ or reeve, normally the richest farmer in the area, would oversee the landowner’s estate.

Penrhys means ‘the head of Rhys’; some people say it’s where local bigwig Rhys ap Tewdwr was beheaded by the Normans in 1090. I suspect that’s all a bit too graphic to be true, and anyway the beheading seems to have happened in Brecon – which doesn’t surprise me.

Pontygwaith means ‘bridge of the work’, a small ironworks which predated the coal industry. Cwmparc is the valley of the park, a mediaeval hunting lodge. ‘Llwyn’ means ‘bush or grove’; so Llwyncelyn is ‘holly grove’.

And those of us who came into this world in Llwynypia hospital – most Rhondda people of my generation – can claim we were born in ‘the magpie’s bush’!

Blaen

‘Blaen’ refers to the source or head of a river or stream, so Blaencwm and Blaenrhondda are the twin heads of the valley. Blaenllechau is ‘the head of the Llechau brook’. Blaenclydach has always slightly puzzled me – literally, it’s ‘the head of the Clydach brook’, though Blaenclydach is down below Clydach Vale. They always do things different up there.

So back home for me, to Penygraig – ‘top of the rock’ – and Tonypandy.

The ‘Ton’ bit – it crops up in Ton Pentre too – means a meadow. And the ‘Pandy’ – that’s a mill, not the type used for grinding flour, but for beating wool to get rid of all the oil and dirt and to make it thicker, a process known as ‘fulling’.

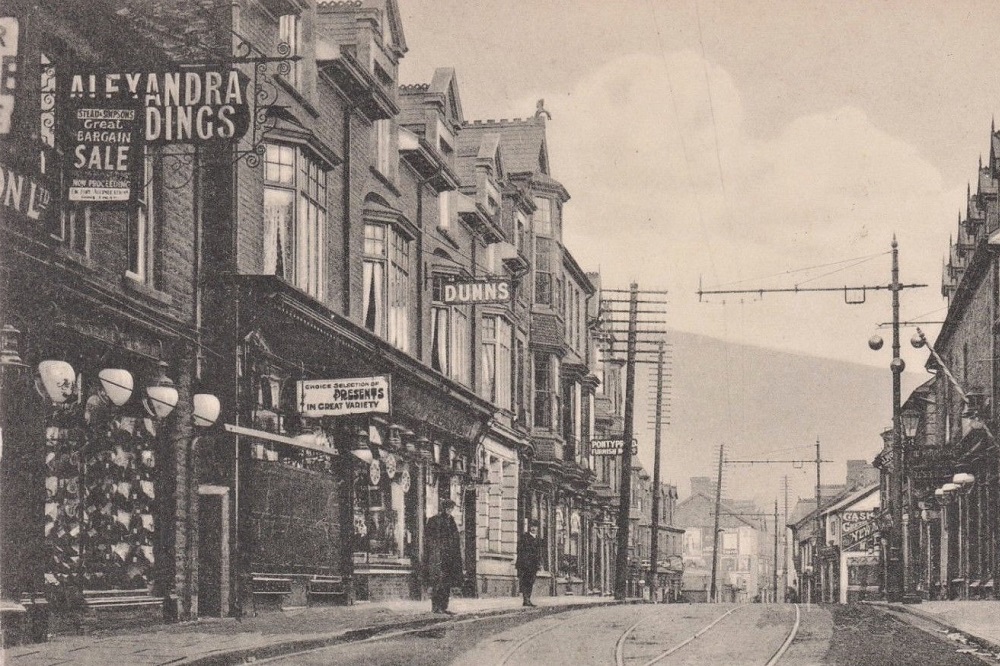

Tonypandy’s old fulling mill stood until the First World War. The hamlet near it was known historically as ‘the Pandy’. The ‘ton’ was on the other side, stretching from the old Cross Keys pub to the Clydach brook, ‘the meadow near the fulling mill’.

Origins

Why does any of this matter? Well, placenames tell us a little bit about the origins of where we live, about where we come from. And in my book, anyway, knowing where we’ve come from is a good start in trying to work out where we’re going.

So, finally, what about the name ‘Rhondda’ itself?

Proper linguists love to argue about this, but the best guess seems to be that the original name was something like ‘Glyn Rhoddne’.

‘Glyn’ is a glen or a valley – straightforward enough.

‘Rhoddne’ or ‘Rhoddna’ – well, that’s a bit more complicated, but the first bit, ‘rhodd’, may be a form of the Welsh word ‘adrodd’, which means to recite or to speak.

‘Rhoddna’ became ‘Rhondda’, in the kind of sound change that swaps letters around over time because… well, because it’s just easier to say the word that way.

So the name of our valley means ‘the vale of the talkative or babbling brook’.

No wonder we like a good natter.

John On The Rhondda’ is broadcast at about 3.15pm as part of David Arthur’s Wednesday Afternoon Show on Rhondda Radio

All episodes of the ‘John On The Rhondda’ podcast are available here

John Geraint’s debut in fiction, ‘The Great Welsh Auntie Novel’, is available from all good bookshops, or directly from Cambria Books

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Ynys is water-meadow or a Lea, so Longlea would be appropriate.

Tre does mean town but it also means home.

Thanks. Throughly enjoyed that as a Penygraig girl.

I was born in Trebanog: or Banog as we used to say and it was certainly high up, I remember walking home from school ( Porth Sec ) ( PGTS ) by Aberhondda Road by the old bus station great times & miss the old place since I moved to Cornwall in 1980 ( steve jones formerly lived at 253 Trebanog Road by the old Spout