Welsh cinema in the English language: is our native talent not good enough?

Stephen Price

It was my fondness for the arts, in particular poetry and cinema, that helped nurture a deep love of Welsh language and culture whilst in high school.

GCSE and A-Level essential viewing included the devastating Hedd Wyn and its snapshot of a history we were never taught; Lois thrust eating disorders and the pain of being a teenager on to the screen with a boldness like nothing I’d ever seen before; Un Nos Ola Leuad with its slow-build to that final harrowing scene; and, of course, Tylluan Wen which is just brilliance made real.

Welsh cinema, with its multitude of talent and unique world-view, showcases a quality that stands shoulder to shoulder with the output of much larger nations. Things are a little quiet at the moment, but the story so far is undoubtedly a triumph, and with such innovative young writers working in Wales today, the seeds have been sown for similar levels of greatness in the future.

Welsh actors in the English language, too, have conquered the world in surprising numbers considering the overall size of our population. From Anthony Hopkins and Richard Burton to Michael Sheen, Taron Egerton and Luke Evans, scene stealing is in our blood and performance in our veins.

English language movies set in Wales, about Welsh people, unfortunately for us all, couldn’t contrast more starkly. And why is this the case, especially when they feature some of the best English language performers out there

Parody

Focusing on some of the more recent offenders, Save the Cinema was released on Sky around a year ago starring the fantastic Samantha Morton. As was no surprise to anyone, her accent sounded like nothing ever heard in Wales before, and the entire production felt like an unintentional parody.

Tom Felton, among other non-Welsh actors, did the best impression he could but sadly it didn’t wash and brought back memories of having my accent repeated back to me, exaggeratedly, by folk from across the border as I’m sure we’ve all experienced in the past.

Gwen, a supernatural horror set in North Wales, was released in 2018, and was high on my to-watch list until the very moment the English leads, Maxine Peake and Eleanor Worthington Cox, opened their mouths.

Conversely, the film brimmed with male Welsh talent including Mark Lewis Jones, Richard Harrington and others, and received generally favourable reviews from critics. This came as something of a surprise to me as, yet again, I sat there criticising every single word uttered as the two leads spoke with two vastly different but similarly inauthentic attempts at Welsh accents.

As we all know, there isn’t one Welsh accent. Most of us can discern striking differences in the accents of people from just a few miles away or pinpoint with alarming accuracy where someone is from.

For a tiny nation, the diversity in our accents and dialects, although fast watering-down, is remarkable and this is an important part of our identity that we need to be proud of and to protect. A stab at a generic one-for-all accent is never going to cut the mustard for a native audience.

There’s almost a level of mockery at the ease in which productions hand out Welsh roles as if we are all simply one British people but with different levels of silly ways to speak. But we’re not just that – we have very distinct cultural identities, so it would be nice if we were sometimes, just sometimes, recognised for that.

Is it any wonder so many other countries use England and Britain interchangeably when, even on this relatively small level, we aren’t even given an opportunity to be represented?

If you hadn’t noticed a theme too, it’s most-often Welsh actresses who lose out on Welsh roles. If we have a Welsh male in the Edge of Love in the shape of Matthew Rhys, this must be balanced out by a non-Welsh female lead in the shape of Keira Knightley.

Again, a superb actress. But why didn’t anyone in the casting department twig that it just doesn’t work? Because to them, a morphing Ruth Madoc impersonation is all it takes to play it Welsh, as long as they don’t bring the xylophone.

I vividly remember switching off Very Annie Mary, starring the extraordinarily talented Rachel Griffiths, some ten minutes after the opening credits, never to attempt again. Similar events took place while watching The Englishman Who Went up a Hill but Came Down a Mountain which features the usually captivating Tara Fitzgerald and Colm Meaney in Welsh roles.

If actors on their level can’t master a Welsh accent or persona then we’re all doomed aren’t we. If only there was a way to get an authentic Welsh performance on screen…

Bridgend

My biggest bone of contention of late came soon after becoming a BFI member. Excited at the prospect of quality cinema after lockdown boredom left little to watch on Netflix and Prime, not to mention the hope of some Welsh classics, I signed up readily.

Surprisingly, I found myself with very little choice from my homeland, but there was at least one film set in Wales that stood out to me at the time and that was the evocatively titled Bridgend.

Its theme needs no explanation to anyone familiar with the Valleys county that made news headlines for the most tragic of reasons back in 2007 and 2008.

Such a film, you’d think, would need to tread very carefully around the subject matter, the people, the multiple complex stories. The region’s darkest days, I’d argue, are for the people of Bridgend to tell, or at the very least, to approve.

The loss of industry, language, culture, purpose – ideas explored bravely in Johann Hari’s book, Lost Connections, can’t be reduced to a commercial movie designed to shock or create a profit, but I went in with an open mind and hoped for the best.

What we got, however, was an English-centred narrative. A fictitious father in the police force and his daughter who had supposedly moved to Bridgend from over the border, and a lead Welsh character played rather incompetently by, surprise, an Englishman.

The film caused a stir in the very place it was meant to represent for all the wrong reasons. Besides opening wounds that had yet, and have yet, to heal, there was also the inescapable absurdity and unfamiliarity of the accents, social lives and behaviours.

Every single detail from start to finish painted this community as childish, brain dead and borderline feral, and it also sidelined the superb acting prowess of Nia Roberts and others who were relinquished to bit parts in case it swayed the English to Welsh ratio into something that might have actually felt believable.

The less said about Bridgend the better, but the very fact that films like this continue to be made in Wales, without any significant Welsh input, and yet serve to represent us on a world stage is simply demeaning.

The conversation isn’t limited to us Welshies either. Gay and trans actors have for a long time now felt shut out of their own stories while the big names take their accolades and job opportunities away left right and centre. Jewish actors, too, complain of Jew Face – the constant dress-up of others when they themselves don’t get a look in.

I get, and have made, the counter-arguments in this very nuanced area, and I’m not suggesting for a minute that only Welsh people should play Welsh parts, since that entirely limits the whole essence of what acting is about, namely, playing another role. It would also limit Welsh actors working outside of Wales. But it is rather galling to be so constantly overlooked for parts that centre on the Welsh experience or represent Welsh people and culture. Throw us a crumb or two now and then, at least.

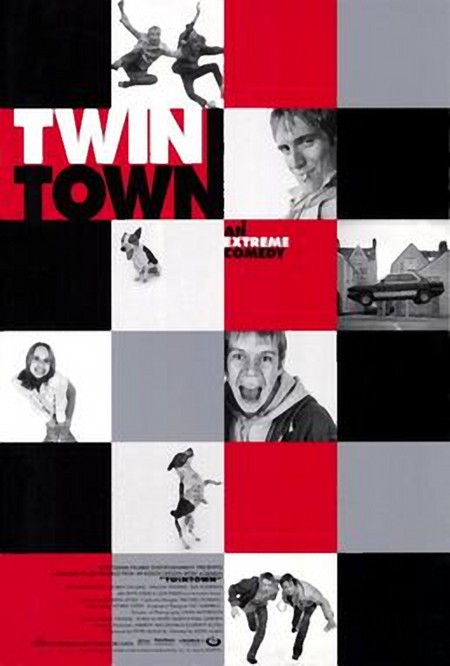

Of course, there have been some great Welsh movies made in English. Solomon and Gaenor, Twin Town and Pride to name but a few, but those films take their Welshness, and their characters’ identities, seriously. They feature the cream of Welsh and other talent. They don’t condescend their audiences and they live on in our collective consciousness, and win awards, for a reason: they had the best people for the job.

By and large, however, we’ve barely progressed since 1941’s supposed masterpiece, How Green Was My Valley, complete with its Irish accents and folk dances, and it’s about time our cinematic output matched the quality of Welsh representation on the small screen.

Authenticity is key for any actor, actress and production, and casting directors fail at the outset if they fail to recognise this. And they also, tragically, fail our young Welsh talent, particularly female, before they even get a chance to shine.

Here’s a novel solution: cast Welsh people in Welsh roles from time to time. It might occasionally result in a good movie.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

I agree. On a slightly different note the drama White House Farm starring the very talented Stephen Graham is set in England and Graham plays the part of a Welsh detective. It is unbelievable that the creators of this play would choose Graham to play this part as his Welsh accent is comical and cringe worthy.

I am sure that casting in films should be decided by how Welsh an actor is,however this is somewhat overshadowed by some real world questions,who is available,who can we afford and who will the punters pay to watch.

Dear heart, it is called acting. Indubitably, if more Welsh people went to Eton they would get more parts (or if they had the surname Fox)

Twin Town was fantastic. Purely because it was authentic. An example of where Welsh people rolled up their sleeves and did it for themselves. A good ethic/principle/philosophy there … rolling up our sleeves and doing it ourselves. I like that idea …

No, the problem is that anything that leaves this island is for the most part anglicised to the extreme. It’s almost as if anything Welsh isn’t allowed to go big. Howls moving Castle, Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones are some examples that come to mind. Even Americans with Welsh surnames are told to change them if they want to make it big, only for English actors that share the same name not being asked the same thing. As if they want people believing Welsh names are English…. These are some examples as to why Wales is hardly known… Read more »

Good article. Two follow-up points: