Yr Hen Iaith part seventeen: Rhonabwy’s Dream and Political Reality

Continuing our series of articles to accompany the podcast series Yr Hen Iaith. This is episode seventeen.

Jerry Hunter

This medieval Welsh tale is startlingly unlike every other Welsh Arthurian narrative (indeed, it is unlike any other tale in any language).

Rhonabwy’s Dream combines a critical look at contemporary Wales with a dream journey back to an unnerving version of the legendary Arthurian past, and it criticizes the warlike ethos which it at times pretends to glorify.

The weapons, armour, horses and banners of warriors are described in effusively glorious detail, but the warfare for which such things exist is ultimately shown to be something which should be avoided at all costs.

Internal violence

What kind of contemporary Wales do we have in this text?

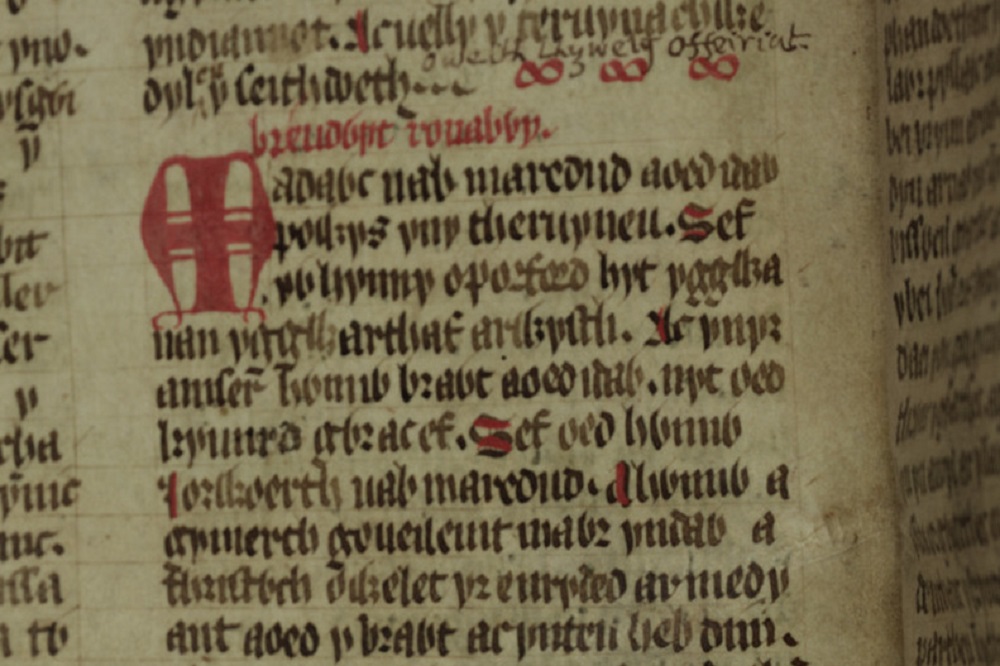

The opening section of the story describes a very real episode in medieval Welsh history, a dispute between Madog ap Maredudd, prince of Powys between 1132 and 1160, and his brother Iorwerth Goch ap Maredudd.

During the two decades leading up to Madog’s reign, the royal family of Powys was plagued by internal violence. And, after Madog’s death in 1160, Powys was divided between a number of his male relatives and never to be united again.

And so – in terms of both what went on in Powys immediately before 1132 and what happened immediately after 1160 – the years of Madog’s reign are shown in sharp relief by the periods which book-end them as a period in which there was hope of achieving some stability and peace.

The fact that strife with his brother Iorwerth Goch threatened that stability makes this a crucial episode in medieval Welsh political history.

Disgusting

Enter Rhonabwy, a fictional character inserted by the tale’s anonymous author into this highly charged historical context. He is one of several messengers sent by Madog ap Maredudd to seek Iorwerth Goch in hopes of avoiding more trouble.

During the course of that crucial mission, the messengers come to the house of a man named Heilyn Goch fab Cadwgan where they spend the night.

The description of this place is memorably disgusting; the ‘floor [is] uneven and full of puddles’ ([ll]awr pyllog anwastad) and it’s slippery because of the ‘cattle’s dung and their urine’ ([b]iswail gwartheg a’u trwnc).

When one of the men steps in a puddle, he soaks his foot up to his ankle in a mixture of water, dung and urine. This is a memorable description of poverty, a grotesque and extreme portrait of what internal feuding does to Welsh society.

When Rhonabwy finally finds the only place in the house where he can make his bed without being plagued by fleas, he sleeps. And he dreams.

Looney Tunes

In that dream he and his companions are travelling in a familiar part of Wales, moving in the direction of Rhyd-y-Gores on the Severn (Hafren).

Familiarity soon yields to strangeness and wonder as a giant warrior on a giant horse appears and chases them. In a scene befitting a Looney Tunes cartoon, when the huge horse exhales, the fleeing men are pushed away from it, and when it inhales, they are sucked back towards it.

The little men are of course overtaken and the giant rider, Iddawg Cordd Prydain (‘the Embroiler of Britain’), takes the men to the Emperor Arthur, who is encamped near the river with his great host.

The martial finery of the warriors is described in great detail but, if we are at times distracted by the trappings of glorified war, we are also reminded that real warfare awaits: Osla Gyllellfawr – ‘Osla Bigknife’, a legendary reflex of the Anglo-Saxon king of Mercia, Offa for whom the famous Dyke is named – is also camped nearby with his army.

Like Iddawg and his steed, all of the men and horses in Arthur’s camp are giants to Rhonabwy’s little eyes.

Arthur’s reaction upon seeing the messengers from Madog ap Maredudd’s Powys is described wonderfully:

Sef a orug yr ymherawdr, glas owenu. “Arglwydd,” heb Iddawg, “beth a chwerddi di?”

“Iddawg,” heb yr Arthur, “nid chwerthin a wnaf, namyn truaned gennyf fod dynion cyn fawhed â hynny yn gwarchadw yr ynys hon gwedi gwŷr cystal ag a’i gwarchedwis gynt.”

What the emperor did was sort-of smile ironically.

“Lord,” said Iddawg, “at what do you laugh?”

“Iddawg,” said Arthur, “I do not laugh, but rather how sad I am [at seeing that] men as lowly as that protect this island after men as good as those who protected it before.”

Leadership

Just as Arthur’s sadness is at first mistaken for mirth, so we are forced to examine and re-examine our views on leadership, warfare and the literature which glorifies treats these themes.

Part of the mechanism forcing this contemplation is the controlled collision between Arthur’s heroic age and the debased state of a ‘real’ Welsh kingdom which the author creates for us.

While waiting for the big battle to begin, Arthur decides to play a wargame with one of his stoutest war leaders, Owain fab Urien.

The game is gwyddbwyll, but, unlike 21st-century Welsh speakers who use this term for what English speakers call ‘chess’, medieval gwyddbwyll was a different kind of board game.

The name, literally meaning ‘wood-sense’, referred originally to the fact that players use pieces carved of wood to test their wits or sense.

In this tale Arthur’s game pieces are made of gold, not wood, a detail akin to the sumptuous clothing and gilded arms and armour described at length by the author. (By the way, the cognate Irish word fidchell suggests that this was an ancient Celtic game inherited by several branches of the Celtic cultural tree.)

Blood-letting

As Owain and Arthur play their game, violence breaks out between their followers. Messengers come several times telling them in alarming detail about this internal blood-letting, but, rather than stopping play in order to make peace in their camp, the two leaders continue their game stubbornly.

Finally, Arthur acts, pulling himself out of the game and smashing the gold gwyddbwyll pieces to dust.

His decision to end the war game also ends the fighting in his camp. It also forestalls the battle with Osla Bigknife, as readers soon learn. He has chosen action over playing games and peace over war.

If Rhonabwy’s dream journey from a troubled present to the legendary age of Arthur is used to make a political point, so must Arthur learn lessons about war and peace in the midst of his world’s wondrous pomp and splendour.

Further Reading:

R. Davies, The Age of Conquest [:] Wales 1063-1425 (Oxford, 1987)

Gwyn Jones and Thomas Jones (translators), The Mabinogion (revised edition, London, 1993)

Sioned Davies (translator), The Mabinogion (Oxford: OUP, 2008)

Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan a Erich Poppe (goln.), Arthur in the Celtic Languages (Caerdydd: Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru, 2019)

Catch up on the previous episodes here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Dim ond i ddweud nad oedd llais Jerry yn glir iawn bob amser.