Yr Hen Iaith number forty six: Exiles, Secret Networks and Literary Milestones

We continue the history of Welsh literature to accompany the second series of podcasts in which Jerry Hunter guides fellow academic Richard Wyn Jones through the centuries. This is episode forty six.

Exiles, Secret Networks and Literary Milestones: Welsh Catholic Literature of the Elizabethan Age

Jerry Hunter

After the Protestant queen Elizabeth I came to the throne, English and Welsh Catholics who did not want to renounce their faith or face a martyr’s death fled to the continent. In 1567 one of these exiles, Morys Clynnog, wrote a letter from Rome to Sir William Cecil, Secretary of State and chief advisor to Elizabeth I, thanking him for his help. And this intriguing letter was written in Welsh. It begins like this:

Urddasol hybarch, gyda’m gorchmynion atoch yn ymysgaroedd Iesu –

Hyn sydd i ddeisyfu arnoch fy scusodi na scrifennais erioed cyn hyn ddim

Atoch, ag i ddiolch i chwi am y gennad a gowsoch i mi gen Ras y Frenhines . . . i ddyfad ag i drigo allan o’r deyrnas[.]

‘Honorable venerated one, with my salutations to you in Jesus –

This is to beseech you to excuse me for not writing anything before this to you to thank you for the permission you got for me from her Grace the Queen . . . to come and reside out of the kingdom.’

Unyielding

If Morys Clynnog strikes a thankful tone, he is also unyielding; his main reason for writing was to beg William Cecil to persuade Queen I to return to the Catholic faith. Cecil was of Welsh descent and might’ve understood the language. Clynnog also might have assumed that a Welsh person working for the Secretary of State could translate the letter. Why did the Catholic exile write in Welsh?

A university-educated humanist, he could of written to Cecil in English or Latin. The choice of language was not to ensure secrecy; Clynnog would’ve been painfully aware of the fact that there were many zealous Protestants serving Elizabeth I, some of them engaged explicitly in the work of rooting out secret Catholic networks. Welsh must have been chosen in order to highlight a bond of some sort, appealing to Cecil’s Welsh heritage and perhaps also to the Welsh origins of the Tudor dynasty.

Clynnog was appointed Bishop of Bangor in 1558 shortly before the Catholic queen Mary I died, a post he was not able to assume. His friend Gruffudd Robert was appointed Archdeacon of Anglesey but was also driven into exile before assuming his responsibilities. Recent episodes in this series have focused on what Wales gained because of the confluence of humanism, the printing press and the Protestant Reformation – most notably, William Morgan’s 1588 Bible. However, it is also important that we consider what was lost because of the Reformation.

Alternative history

Here’s a brief outline for an alternative history of the period 1558 to c. 1600, one in which Mary lives a long life and Wales and England remain Catholic. Morys Clynnog is Bishop of Bangor and his close friend Gruffudd Robert is Archdeacon of Angelsey. These two energetic men – both university-educated humanists who are passionate about promoting their native language and its culture – drive a cultural Renaissance in north-west Wales, Catholic in religion and Welsh in language.

All fantasizing aside, it is certain that these two men were driven. Even while living in exile in Italian cities, they managed to publish books in their native language.

Morys Clynnog’s Athrauaeth Gristnogaul (‘Chrisitian Teaching’) was printed in Milan in 1568. This is a Welsh-language catechism designed for teaching basic elements of the Catholic faith. We can imagine that copies of this little Welsh book were the center of Tudor intrigue, smuggled back into Wales and distributed secretly by members of a Catholic underground who were literally risking their lives in doing so.

Linguist

More interesting to scholars of the Welsh language is the book which Gruffudd Robert published in Milan in 1567, Dosparth Byrr Ar y Rhann Gyntaf i Ramadeg Cymraeg, a ‘The First Part of a Short Analysis of Welsh Grammar’. Gruffudd Robert was a talented linguist, and this grammar is one of the best examples of Welsh-language humanist learning produced during the sixteenth century.

This work also has considerable literary merits. It begins with an introduction styled Iaith Gambr yn annerch yr hygar ddarlleydd, ‘The Welsh Language [literally, ‘the Language of Camber’] addressing the dear reader’. The personified Welsh languages thus speaks to the reader, drawing attention to its neglect: E fydd weithiau’n dostur fynghalon wrth weled llawer a anwyd ag a fagwyd i’m doedyd, yn ddiystr genthynt amdanaf (‘My heart is sometimes sick at seeing many who were born and raised to speak me disregarding me’). Gruffudd Robert piles on the guilt:

. . . oblygyd hynn yddwyf yn adolwg i bob naturiol gymro dalu dyledus gariad i’r iaith gymraeg; fal na allo neb ddoedyd am yr vn o honynt mae pechod oedd fyth i magu ar laeth bronnau cymraes[.]

‘Because of this I implore every natural Welshman to give the Welsh language the love it deserves, so that nobody can say about any of them that it was a shame that he was raised on the milk of a Welsh woman’s breasts.’

This is a memorable episode in the international history of the Welsh language; a man writing in Welsh in Milan is chastising people back in Wales for neglecting their native tongue!

Powerful

The grammar’s prologue is another powerful work of literature, cast as a dialogue between fictionalized versions of the author and his friend Morys Clynnog. It presents a charming picture of the two exiled Welshmen enduring an Italian summer. Gruffudd begins by noting that they have left the house where ‘unreasonable heat’ (gures anosparthus) and the ‘sultriness’ (myllni) ‘from a lack of air and breeze’ (o eisiau auyr a guynt) was ‘troubling’ (poeni) them and ‘enough to suffocate people’ (dygon i fygu dynnion). But they are now ‘more comfortable’ (yn esmuythach), having found a nice place to sit outside, where ‘the branches and leaves of vines’ (cangau a daily guinuyd) shelter them ‘from the sun’s rays’ (rhag pelydr yr haul), and a ‘slow wind from the north cools’ (guynt arafaid o’r gogled yn oeri) them.

Sitting in the shade of an Italian vineyard, the two suffer hiraeth, an intense longing for Wales and all that they used to enjoy at home. They miss listening to the harp, the performance of Welsh poetry, and stories being told about ‘every amazing and praise-worthy feat which was done in the land of Wales long ago’ (bob gueithred hynod, a guiuglod a uneithid truy dir cymru er ys talm o amser). Gruffudd Robert crafted this dialogue so that it leads us from the Italian climate to the Welsh climate to Welsh culture and then on to the book’s main event, a detailed discussion of the Welsh language.

Printed in a cave

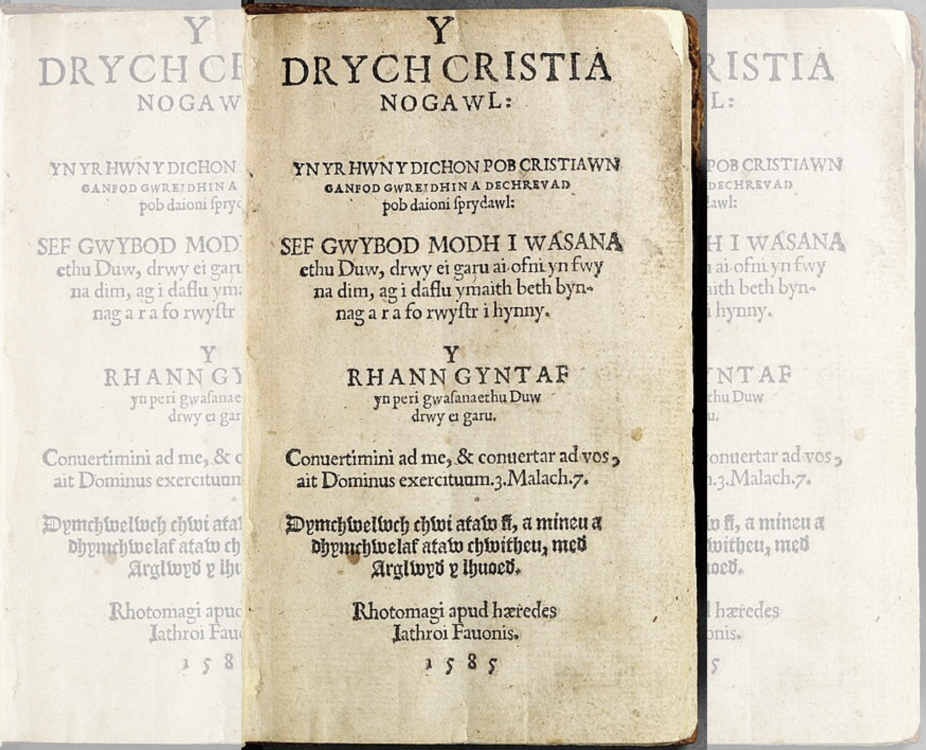

Both Gruffudd Robert and Morys Clynnog have been connected with Y Drych Cristianogawl, an anonymous Catholic book printed in 1586 or 1587. The title page claims that the book was printed in Rouen in 1585, a ruse meant to confuse the authorities, for the book was printed in a cave in north Wales. William Griffith, M.P. for Caernarfon and admiralty judge, worked to uncover Catholic activities in north Wales. In a letter to John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury, this Welsh Protestant enforcer describes the cave’s location: ‘in the Counteye of Carnarvon . . . there is a place called Gogarth . . . twelve miles from Bangor . . . & ther is a Cave bye the Sea side[.]’

The fact that Y Drych Cristianogawl was produced by Catholics who took their lives in their hands by printing this Welsh-language book in Wales is interesting enough. However, they also managed to produce the first book ever known to have been published in Wales.

As noted previously in this series, Tudor law restricted the printing press, forcing Welsh Protestant humanists to travel to London in order to produce the first Welsh books. Books would not be printed legally in Wales until the very end of the following century. If the pioneering Welsh grammar which Gruffudd Robert produced from exile in Milan is a milestone in the history of Welsh writing, the group of daring Catholics who printed Y Drych Cristianogawl in a cave in north Wales produced a literary milestone of a very different kind.

Darllen Pellach / Further Reading:

For the full text of Morys Clynnog’s letter to William Cecil, see Thomas Jones et al, Rhyddiaith Gymraeg [:] Yr Ail Gyfrol 1547-1618 (Caerdydd, 1956)

Geraint Gruffydd, ‘Gwasg ddirgel yr ogof yn Rhiwledyn’,Journal of the Welsh Bibliographical Society,Vol. 9, no.1 (July, 1958).

Geraint Bowen, Welsh Recusant Writings (1999).

Angharad Price, Gwrthddiwygwyr Cymreig yr Eidal (2005).

Angharad Price, ‘Y Cymry yn yr Eidal’ in Gororion (2023).

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.