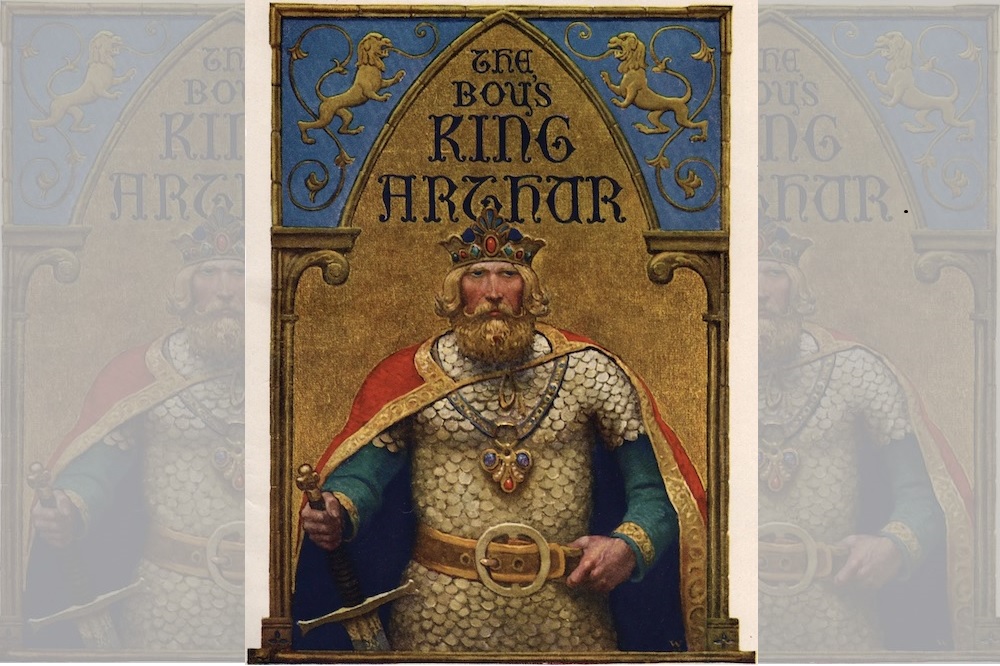

Yr Hen Iaith part eleven: Arthuriana – the Greatest Welsh Gift to the World?

Jerry Hunter

Continuing our series of articles to accompany the podcast series Yr Hen Iaith. This is episode eleven.

In this episode I suggest that the greatest gift Wales has given to the rest of the world is the Arthurian tradition.

And by ‘greatest’, I mean a Welsh cultural product which has had been adopted by the largest number of different languages and nations and embraced with the greatest enthusiasm.

Admittedly, I said this in an off-the-cuff manner without any scientific evidence to back it up. So I’m pausing as I write this – at 11.37 pm on 23 May 2023 – in order to type the words ‘King Arthur’ into Google. The search engine tells me that there are ‘about (tua) 346 million’ hits.

Now I’ve typed in ‘Welsh music’ and had ‘about 321 million’ hits. ‘Welsh rugby’ yields ‘about 88.2 million’ and ‘the Welsh national football team’ comes up with ‘about 66.1 million’.

Drilling down to a more detailed level, ‘Excalibur’, the English name for Arthur’s famous sword, yields ‘about 44.2 million’ items and its Welsh name, ‘Caledfwlch’, gives ‘about 38,700’.

Ok, this is still not very scientific, but you get the idea. In all honesty, I simply can’t think of anything else created by the Welsh which has had such an impact on the cultural lives of other peoples.

Hollywood

By the end of the Middle Ages the Arthurian tradition had spread across Europe (and we’ll try to devote a future episode to discussing the nature of this spreading).

Arthurian texts were written in many medieval European languages, not just the well known French, German and English material, but also literature in other languages, including Irish, Spanish and Icelandic.

Fast forward through all of the Arthuriana produced during the following centuries to the 20th and 21st centuries, and think of the ways in which Arthurian legend has been used in Hollywood films, computer games, fantasy novels, and Japanese anime.

All of this began in Wales – or at least in the Welsh language (remembering that the language was spoken beyond the present borders of Wales in the early Middle Ages).

If the Welsh could’ve copyrighted King Arthur, it would’ve made the nation more money than the Marvel franchise has made for Disney.

Folklore

The historicity of Arthur is a huge area of debate and – as we are concerned here with the literature, not the history – we’ll summarize briefly and move on. It is certain that there was no ‘King Arthur’.

It is safe to postulate, though, that, after the collapse of Roman power in Britain, a war leader named something like Artōrius led Brythonic Celts against the invading Anglo-Saxons.

The Historia Brittonum, that Latin text most likely written in Gwynedd in the court of Merfyn Frych during the first half of the 9th century, calls Arthur ‘dux bellorum’, a ‘lord of battles’ or ‘war leader’.

While the earliest relevant sources are in Latin, there is evidence that they were inspired by existing Welsh-language tradition.

This includes onomastic legends explaining Welsh place names – for example, Carn Cabal, a monumental pile of stones in the region of Builth said to have the pawprint of Cafall (Latinized as Cabal), Arthur’s dog, left when hunting the ‘boar Troynt’ (which can be connected with the Twrch Trwyth in the Welsh tale, ‘Culhwch and Olwen’).

The Latin author had to following a tale told in the Welsh language, thus proving that was already a body of Welsh folklore centring on the exploits of Arthur by the early 9th century.

Exactly how far back do these traditions go? It is impossible to say. However, Gildas’s 6th century work ‘About the Destruction of Britain’, De Excidio Britanniae, mentions the battle of Badon (or Baddon, to use the Welsh form of the name).

Gildas does not mention Arthur by name, but this is one of the battles associated with the legendary leader in later Latin writing.

The Annales Cambriae (‘The Chronicles of Wales’) contains a list of these battles, including the Battle of Baddon in the year 516 A.D., when Arthur, it says ‘carried the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ on his shoulders for three days and three nights’.

Battle

By the way, this is most likely evidence that the Latin author misread a pre-existing and now lost Welsh text he was using for source material which said that Arthur had the Christian Cross on his ‘shield’ (ysgwyd in Welsh) during the battle, taking the word to mean ‘shoulder’ (ysgwydd), as both words could be spelled the same way in Old Welsh.

This list also locates Camlan, Arthur’s final battle, in the year 537, noting that both Arthur and Medrawd (his nephew and adversary in later medieval Welsh texts) fell there.

There is poetry contained in medieval Welsh manuscripts which provides tantalizing glimpses of early Arthurian tradition.

One of them, ‘Pa ŵr yw’r Porthor’ (‘What man is the Gatekeep?’), preserved in the Black Book of Carmarthen (c. 1250), asks us to imagine Arthur wandering with a small band of warriors, coming to the gates of a court, fortress or castle.

It is a dramatic poem, cast as a dialogue between the two legendary figures, one outside and one inside the gates.

Pa gur yv y porthaur. ‘Pa ŵr yw’r porthor?’

Gleuluid gauaeluaur. ‘Glewlwyd Gafaelfawr;

Pa gur ae gouin. Pa ŵr a’i gofyn?’

arthur. A chei guin. ‘Arthur, a Chai gwyn.’

Pa imda genhid. ‘Pa ymdda gennyt?’ [ymdaith, ymddaith]

Guir gorev im byd. ‘Gwŷr gorau yn y byd.’

ym ty ny doi. ‘I mewn i’m tŷ ni ddoi di

Onys guaredi. Onis gwaredi [siarad ar eu rhan]’

[Arthur:] ‘What man is the porter?’

[Glewlwyd:] ‘Glewlwyd Gafaelfawr [Great-Grasp]

‘What man asks it?’

[Arthur:] ‘Arthur, and Blessed Cai.’

[Glewlwyd:] ‘What companions travel with you?’

[Arthur:] ‘The best men in the world.’

[Glewlwyd:] ‘Into my house you will not come,

‘unless you vouch for them.’

Heroes

Arthur then lists some of the heroes travelling with them, giving names which appear in later Welsh texts (and which were transmuted into the names of Arthurian heroes in other languages after this Welsh legendry became a pan-European tradition).

This intriguing poem could’ve belonged to an older Welsh tradition in which Arthur was not king but rather the leader of a warband (thus echoing the suggestions of the earliest Latin sources).

Or it might’ve been part of a tale in which Arthur had been deprived of kingship by some means, doomed to wander, an outsider in his own land, forced to ask permission to enter what used to be his own court. In later Welsh

King (or ‘Emperor’) Arthur’s court. This poem from the Black Boor reminds me in tone of the Irish traditions concerning Fionn mac Cumhall, that wondrous hero who lives in the wilderness, outside of mainstream society, wandering with his Fianna or band of heroes.

Legendary

Like the listing of heroes in this Black Book poem, early poetry recorded in the Book of Taliesin suggests the way in which Arthurian tradition attracted legendary figures who originally inhabited their own stories.

It is as if Arthur became a huge magnet in Welsh tradition, attracting other characters and pulling them out of their own legends in order to play supporting roles in his big story.

Other figures become satellites orbiting Planet Arthur, pulled in by his great, overwhelming gravity. This happens in an extreme form in the list of Arthurian characters found in the tale ‘Culhwch ac Olwen.’

The medieval triads are invaluable sources for early Welsh Arthuriana. In some of them, Arthur is a fourth name following the three legendary figures, presented as surpassing all of them.

For example, Tri Hael Enys Prydein, ‘The Three Generous Ones of the Island of Britain’, lists Nudd Hael, Mordaf Hael and Rhydderch Hael, before going on to conclude that ‘Arthur himself was more generous than the three’ (‘Ac Arthur ehun oedd haelach no’r tri’).

Magic protection

A comment appended to Tri Matkud Ynys Prydein, ‘The Three Good Concealments of the Island of Britain’, states that Arthur dug up the head of Bendigeidfran (one of the three buried things, mad or ‘good’ because burying them provided magic protection for the realm), ‘because he did not like having this Island guarded by the power of anybody except his own’ (Kan nyt oed dec gantav kadv yr Ynys honn o gedernit neb, namy o’r eidav ehun).

My personal favourite is Tri Gwrfeichiad Ynys Brydain, translated by Rachel Bromwich as ‘The Three Powerful Swineherds of the Island of Britain’.

This short text contains a medieval Welsh micro story which tells how Arthur gathered his hosts in order to hunt and destroy pigs, following a prophecy that these animals would wreak great destruction.

And here is another link with the earliest surviving vernacular tale featuring Arthur, ‘Culhwch ac Olwen.’ We’ll have to talk about that tale in detail soon. Tune in later for more stories from Planet Arthur.

Further Reading:

Rachel Bromwich, A. O. H. Jarman a Brynley F. Robers (goln.), The Arthur of the Welsh: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval Welsh Literature (Caerdydd, 1991)

Rachel Bronwich (gol.), Trioedd Ynys Prydain [:] The Triads of the Island of Britain (Caerdydd, 1961 [4ydd argraffiad 2014])

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

A lot of ignorant English think he was an English king and is revered to as a King of England

So tell me why have you delated my comment are you afraid that i have upset english people

Diddorol iawn

Unfortunately most of the rest of the World and the English themselves believe, irrationally, that King Arthur was an English King and have little appreciation of the history behind the figure. The mythical figure is obviously a composite, ie invasion of Europe – Macsen Wledig & Sons. Personally I think that Alan Wilson & Baram Blackett, plus Chris Barber have come closest to unravelling the mystery.

Indeed, I also believe them when they say “the only mystery surrounding Arthur, is why it’s a mystery”. As the amount of evidence provided is quite something. The craziest part is the refusal to accept him as one of theirs by the Welsh themselves. For some reason The Britons themselves don’t want him associated with Wales. It’s really bizarre. I guess this may be a result of England controlling your education for over 300 years. And as you said, the idea that he is an English king is weird. How could he be if he thought the Anglo Saxons, who… Read more »

Perhaps I was lucky, despite going to primary in Cardiff in the 60s, we were read the myths of Arthur, of course buried up the Neath Valley. At that time St Davids day was the school Eisteddfod and a half day holiday. There seems to be only time for facts nowadays and definetly no half day holiday.

And more recently the departed Ross Broadstock who took on the torch from the good men you mention.

A gift to the world? Yeah, such a gift the stories surrounding the potential real world Arthur were plagiarised by the English and French. To the point where most people now ridicule the idea that he originates in Wales.

Great article. Interesting program on BBC4 re King Arthur with Alice Roberts the other night. Also, hasn’t a coin turned up, forcing the historians to re evaluate, positively, Arthur’s position in the scheme of things, showing an alliance of some sort.

Tongue in cheek, I might suggest that there are a couple of Welsh inventions that are popular world wide and which probably have mega hits, not that I’ve looked:

NHS,

Old age pension,

Unemployment benefit

They are of Welsh origin, born out of our society

There are more than that! Packet switching for example was perfected by Donald Davies! This is a vital and core component for the Internet. It breaks down information and reassembles it….Wales also developed the first fuel cell (William Robert Grove), Mail order, Sleeping Bag and the ball Bearing. Chain mail and Longbow are also credited to the ancient Brythonic people.

Arthur mentioned in the Welsh 13 Treasures of Britain. Perhaps a source for JK Rowling’s HP books films, as invisible cloak, chessboard etc some of the treasures.

It’s odd that America changed the title of HP and the philosopher’s stone to HP and the sorcerer’s stone, as the philosopher’s stone the central symbol of alchemy.