Yr Hen Iaith part fifteen: Rock and Roll and the Welsh-European Arthur

Continuing our series of articles to accompany the podcast series Yr Hen Iaith. This is episode fifteen.

Jerry Hunter

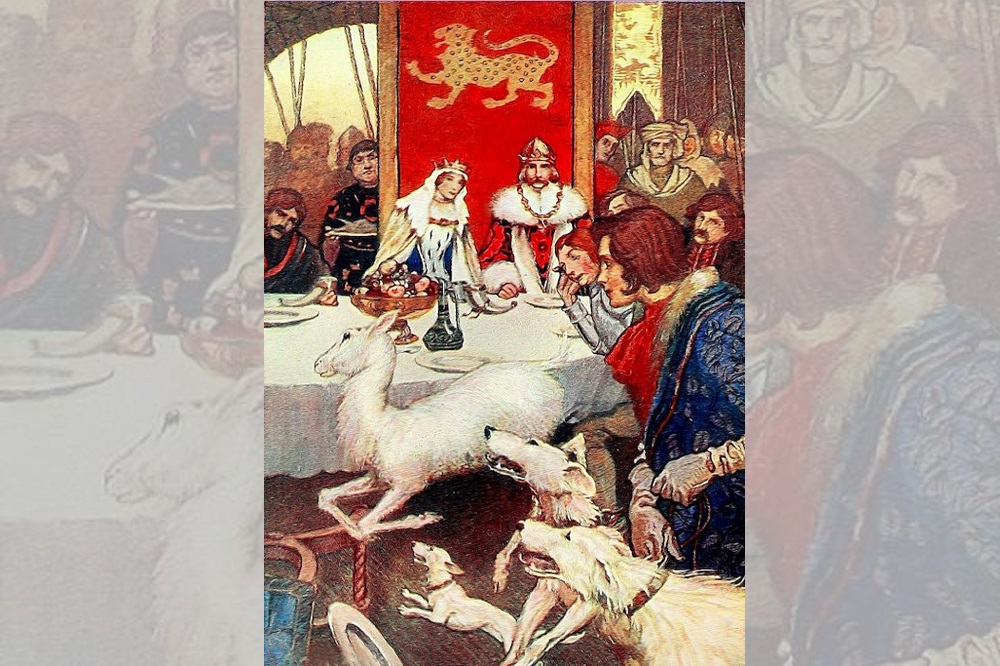

Discussing the development of Arthurian literature provides an excellent opportunity to consider the relationship between Welsh culture and the cultures of other European languages.

As already noted in this series, some medieval Welsh material – poetry, triads and the long tale ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ – can be viewed as manifestations of ‘native’ Welsh Arthuriana.

These texts suggest how Welsh speakers might have considered that body of tradition before it crossed geographical, political and linguistic borders and then came back again, transformed and transforming.

Many themes and characters which people often associate with King Arthur – the Round Table, the Quest for the Holy Grail, Sir Lancelot – came into Welsh after being invented elsewhere, as Welsh views of the legendary Arthurian past became synchronised with an evolving body of European Arthuriana.

Red card

Three of our ‘native’ medieval Welsh prose tales were heavily influenced by this new European Arthurian trend.

Each of these texts concerns a very Welsh hero associated with Arthur’s court – Peredur, Geraint and Owain – yet the world in which these characters move is very different to that of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’.

Indeed, these three Welsh texts are closely related to three long narrative poems by the French poet Chrétien de Troyes.

In fact, one of them is so close to the French version that it has been seen by a translation by some – if that is true, then it should get a red card and reduce our team of eleven native Welsh tales to ten.

We’ll discuss these three tales in detail in the next three episodes, so let’s think now about the nature of transmission across linguistic boundaries and the ways in which ‘foreign’ influences can transform a ‘native’ tradition.

How did Arthurian material first move from Wales to other places?

We have mentioned Geoffrey of Monmouth’s twelfth-century work, Historia Regum Britanniae, which became something of medieval manuscript culture’s version of a ‘best seller’ and – given the fact that it was written in Latin, the language of European learning – it carried an enticing body of Arthurian narratives and a coherent view of Arthur’s age to many other places.

We can also imagine oral tales being transmitted across linguistic boundaries. Norman French came to this island in 1066 with a lot of force behind it.

It would take another 216 years for that advancing Norman military might to conquer all of Wales, but Norman influence, culture and language began reaching Wales long before then.

We can thus imagine bilingual tale-tellers, either professional entertainers or people who simply enjoyed telling a good story, and it only takes one such person to produce a French version of a Welsh tale to kick off a new process of transmission and elaboration.

And, given that some of the first Norman leaders who gained land in south Wales were Bretons, it is also easy to imagine trilingual people, with the Breton language being an easy intermediary between Welsh and French in some contexts.

Elvis

So, how do we think about Arthurian tales which were written in the Welsh language but which display a great deal of French influence? What kind of models help us consider this kind of cultural contact, influence and hybridity?

The history of rock and roll as seen from an American perspective provides one comparison. This kind of popular music evolved out of African-American musical traditions such as gospel and blues.

It became popularized by a number of American artists in the 1950s (Little Richard, Fats Domino, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis and Elvis Presley).

The Who

Rock and Roll was then exported to Britain and inspired musical trends on this island, leading to the emergence of a number of extremely popular British bands in the 1960s (the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Kinks and the Who). Americans then experienced what was called ‘The British Invasion’ as these groups crossed the Atlantic, toured, appeared on radio and television, and sold a great deal of records.

New American bands emerged influenced by this ‘foreign’ rock. So, did an American teenager listening to one of those bands in the early 1970s think about the origins, transmission, development and hybrid nature of that music?

Probably not; that teenager just thought of it as rock and roll. We can think of Arthurian narrative as medieval Welsh rock and roll.

It originated in Welsh, was exported and adopted by the cultures of other languages, transformed, and imported back into Wales where it encouraged the tradition from which it had originated to develop in new ways.

Further Reading:

Rachel Bromwich, A. O. H. Jarman a Brynley F. Robers (goln.), The Arthur of the Welsh: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval Welsh Literature (Caerdydd, 1991)

Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan a Erich Poppe (goln.), Arthur in the Celtic Languages (Caerdydd: Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru, 2019)

Catch up on the previous episodes here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

The Normans could well have been aquainted with Arthur prior to 1066 and all that via their neighbours the Bretons. Of course in 5th 6th centuries Wales and Llydaw – Brittany had very close relations.and Geoffrey’s work just gave it a wider circulation.