Yr Hen Iaith, part fifty. A Poet in Two Worlds: Richard Hughes of Cefnllanfair

Jerry Hunter

As we celebrate the half century of Yr Hen Iaith articles which accompany the ground-breaking and good-spirited podcasts in which the academic friends and friendly academics Jerry Hunter and Richard Wyn Jones take us through centuries of Welsh writing, Nation.Cymru would like to lift a goblet of mead to toast their fiftieth edition.

You are offering us nothing less than an oblique and consistently informative version of an online degree in Welsh literature. Llongyfarchiadau enfawr! Ymlaen! This accompanies podcast 50.

Er cymaint ydyw braint a bri – Llundain

A’i llawnder o arglwyddi;

Hiraeth sy’n faith arnaf fi,

Ambell ŵyl, am Bwllheli.

‘However great are the privilege and fame of London

with its abundance of lords;

Hiraeth for Pwllheli

weighs heavy on me some holidays.’

This englyn was composed by Richard Hughes (c.1565-1619). Originally from Cefnllanfair on the Llŷn peninsula, he spent a great deal of time in London serving as a footman to both Elizabeth I and her successor, and James I.

This Welsh poet certainly did see an ‘abundance of lords’ while working in the royal court. Yet as this powerfully compact strict-metre poem tells us, the dazzling context in which he found himself did not alleviate the intense longing or hiraeth for his home in Wales.

Different worlds

Several poets from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries have left us poetry which testifies to the way in which their lives straddled different worlds, one centered in London and the other back in Wales. Siôn Tudur, a member of that great generation of bardic disciples taught by Gruffudd Hiraethog, also served Queen Elizabeth in London.

More than 300 of Siôn Tudur’s poems have survived and this huge body of poetry testifies to the ways in which he interpreted Tudor society in both London and Wales. The poet Tomas Prys of Plas Iolyn led a varied life, serving as a soldier in several military campaigns and also as captain of his own privateer ship.

He spent a great deal of time in London, including several periods in prison, once for an extremely heinous crime – raping his nice. His surviving poetry touches in one way or another upon all of these subjects. The careers of several Tudor prose writers were also inflected by their time, most notably Elis Gruffydd (see parts thirty-six and thirty-seven in this series).

Dualities

Returning to Richard Hughes of Cefnllanfair, we can say that the poetry by him which survives today is characterized by a series of dualities or dichotomies. In addition to employing the strict-metre englyn form, he wrote a considerable amount of free-metre verse.

He composed elevated love poetry and verse treating sex in an extremely bawdy fashion. He wrote tributes to friends and satires attacking people whom he didn’t like. And he wrote about both London and his home in Llŷn. In one englyn he describes the boat which took people to Ynys Enlli (Bardsey Island) as a caseg, a ‘mare’ travelling from the river Daron to Enlli, ‘leaping over the sea’ (yn llamu gweilgi).

As Richard Hughes apparently enjoyed life in both places, his englyn satirizing a female inkeeper might reflect life in either London or Wales. Complaining that the woman camgyfri, ‘mis-calculates’ the money owed, he calls her a siad anynad, ‘unruly jade’ and rhyw ddiawles, ‘a kind of she-devil’.

Local politics

Despite holding a coveted position in the court in London, Richard Hughes maintained an interest in local politics back home. When a man whom he did not like, Siôn Galgarth, was elected bailiff in Pwllheli, the poet penned a biting englyn which crystalizes his feelings on the matter:

Ai Calgarth, cyfarth pob ci – hen Suddas

Sy’ swyddog Pwllheli?

Os y filain sy faeli,

Gawell brwnt, nid gwell ei bri.

‘Is it Calgarth, every dog’s barking [a man every dog barks at?] – an old Judas

who is Pwllheli’s official?

If the scoundrel is a bailiff,

the dirty belly, his fame is no better.’

In other words, the man is the same even though he now holds an important position. In another englyn Richard Hughes describes the new toilet which Siôn Galgarth had built onto his house. This would’ve been a protrusion on one side of the building, so that the waste could drop out onto the ground below.

Gwychdeg i’w weled o gachdy – yw hwn

O’i hanner i fyny;

Baw cna’ crach newydd gachu

Sy’ ymhob man dan ei dŷ.

‘This is a brilliantly wonderful shithouse to behold

With half of it sticking up;

the recently-shat waste of a scoundrel

is everywhere below his house.’

So much for the latest in home renovations! However, this pointedly scatalogical satire shows how poetry could be used to draw attention to social pretention and conspicuous spending. The suggestion is that Pwllheli’s socially-climbing offical was proud for people to see this new addition to his house, a sign of the wealth he was making and spending.

By lowering our eyes from the archetictural feature to what lies below it, the poet compeletely undermines attempts at gaining respect in this way.

Wealth

The uses and value of wealth is examined critically in a very different poem by Richard Hughes. This is a free-metre piece in which he claims to present an overhead conversation between two lovers. Though a ‘gentleman’ (gŵr bonheddig), the man was poor, and the woman, in contrast, was ‘[c]yfoethog’, ‘wealthy’.

Taking us into the dramatic present tense of the story, the poet gives us the mans words:

‘Doedwch imi yn ddiomedd

Ai eich da, ai’ch pryd, ai’ch bonedd,

Ai eich rhinwedde, deuliw’r ôd,

Sy’n peri i chwi fod mor rhyfedd?

‘Tell me without refusal:

is it your possessions, or your appearance, or your lineage,

or your virtues, one fairer than snow,

which makes you be so strange?’

He then addresses these superficial attributes which set her apart from him, beginning with her wealth, reminding her that noeth y daethoch, noeth yr ewch (‘naked you came [into the world], [and] naked you will go [from it]’). After noting that oedran (‘age’) is one of many things than can take away her good looks, he goes on to address the question of pedigree:

Os eich bonedd, gwen liw’r manod,

Sy’n peri i chwi fy ngwrthod;

Yr un Gw^r gorucha’ a’n gwnaeth

O’r un rhywogaeth dywod.

‘If it is your lineage, fair one the color of fresh snow,

which causes you to refuse me;

[remember that] the same God on high made us

from the same kind of earth.’

Love

There are plenty of narrative poems from the period in which a difference in class and/or wealth comes between lovers, but Richard Hughes has love triumph in the end. In the final verse, the woman calls him ‘my true heart’ (fy ngwir galon) and states that she will go with him, ‘come what may’ (doed a ddelo).

In another free-metre composition, Richard Hughes presents a different kind of dialogue in which wealth – or the lack of it – is also a central theme. As the opening lines tell us, this is a conversation between the poet’s persona and an old man begging for money:

A m’fi’n rhodio glan y dŵr,

Cy’rfûm â henwr difri,

Ag aml glwt ar ei glog

Yn gofyn ceiniog i mi.

‘When I was strolling alongside the water,

I met an earnest old man,

With many a patch on his cloak,

Asking me for a penny.’

He gives him ‘a little penny’ (ceiniog bach), explaining that he can’t afford to give any more:

Cymrwch hyn, trwy ‘wyllys da,

A mwy ni alla’ch helpu;

Sawdwr wyf a serfing man,

Nid oes fawr arian gen i.

‘Take this, through good will,

But I can’t help you any more than that;

I am a soldier and a serving man,

And I don’t have much money.’

Note the English phrase serfing man in the original Welsh text; this sounds like a real conversation conducted using the colloquial speech of the day. The old man replies A hwde d’arian elwaith, ‘and here is twice [the value of] your money’. He then gives him advice, telling him that he led a similar life when he was young:

Tra fûm ifanc bûm ddyn gwych –

Y modd yr ydych chwithe;

Ond cerdota’ yr wyf i’n awr

Trwy newyn mawr, ac eisie.

‘When I was young a was a slenpdid man

the same way you are now –

But now I am living on charity,

Suffering great hunger and want.’

Resonating with themes relevant today, we are forced to contemplate what happens to injured soldiers discarded by those whom they served:

Pan droir chwi allan, mewn awr bach

Yr ewch i yn gleiriach ysig;

Megis ceffyl hen, pan droer

I borfa oer, fynyddig.

‘When you are turned out, in a short while,

you’ll become a broken old man;

like an old horse, when it’s turned out

to a cold mountain pasture.’

Further Reading

Enid Roberts (ed.), Gwaith Siôn Tudur, (1980). Two volumes.

Jerry Hunter, ‘“Ond Mater Merch”: Cywydd Llatai Troseddol Tomos Prys’, Llên Cymru 46 (2023)

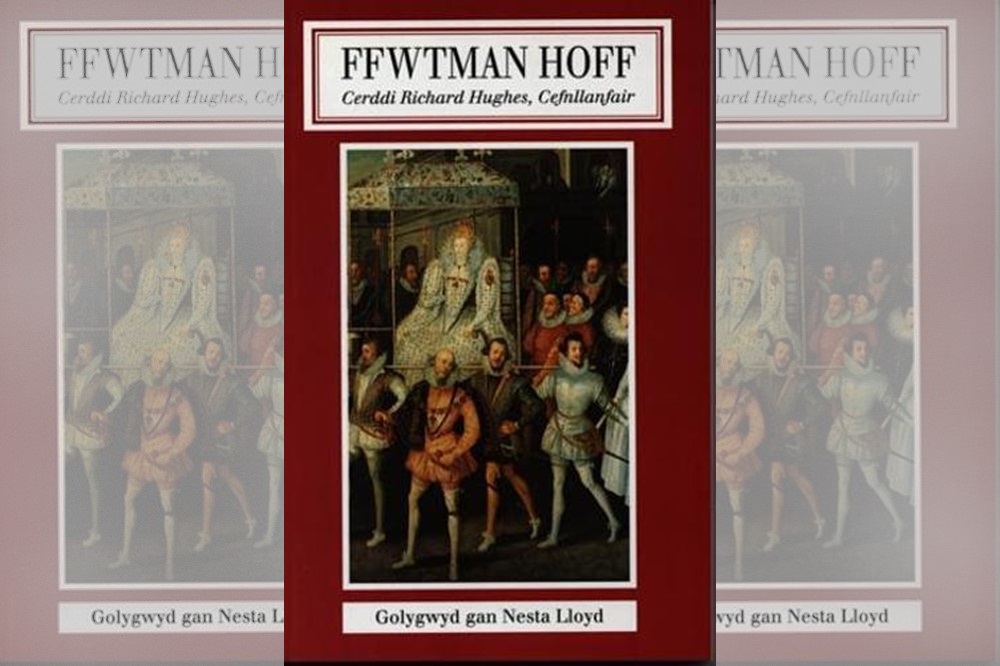

Nesta Lloyd (ed.), Ffwtman Hoff: Cerddi Richard Hughes Cefnllanfair (1998)

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.