Yr Hen Iaith part fifty two: The Little Bible of 1630

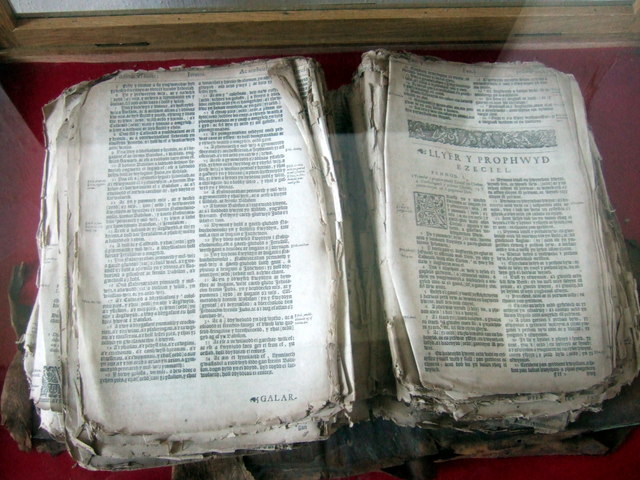

Photo by ceridwen/still surviving via Creative Commons licence CC BY-SA 2.0

We continue the history of Welsh literature to accompany the second series of podcasts in which Jerry Hunter guides fellow academic Richard Wyn Jones through the centuries. This is episode 52.

‘A Friend, Dear Person and Chief Advisor’: The Little Bible of 1630

Jerry Hunter

We must return to the Bible in order to understand to development of Welsh literature in the seventeenth century. This series has dealt in some detail with the significance of the 1567 Welsh New Testament and the complete translation by William Morgan published in 1588. The next milestone was a revised version published in 1620.

While Bishop Richard Parry has been credited, it is widely accepted that the Oxford-educated humanist John Davies of Mallwyd was the real force behind the 1620 Bible; he had been at work studying Welsh grammar in detail for years, and was thus ideally suited to the task. The next milestone came ten years later with the publication of Y Beibl Bach (‘the Little Bible’).

While not differing in language from the 1620 publication, what made the 1630 Little Bible important was the new format. The 1588 and 1620 publications were pulpit bibles, large volumes intended only for use during church services and too expensive for any but the wealthiest to afford.

Being a smaller, more compact book, the Little Bible was intended for consumption beyond the walls of the church. While Welsh people had been hearing William Morgan’s elevated literary Welsh in church for decades, many of them could now read it daily in their homes.

This would have a huge impact on religious history in Wales, being one of things which encouraged the slow growth of Puritanism. It was also a milestone in terms of Welsh literary history; literacy is essential if writers are to have readers, and no single development encouraged the spread of literacy more than having at least one book in people’s homes.

Significance

We don’t know who wrote an original piece of Welsh prose included in the 1630 Beibl Bach, but it is an extremely interesting text in its own right, crafted by a skilled author who employed a range of rhetorical strategies in order to draw attention to the significance of the publication.

It begins by validating the importance of vernacular languages, referring to the narrative in the Book of Acts describing how the Apostles came to ‘speak with other tongues’ (llefaru â thafodau eraill). The emphasis is on the importance various peoples place on hearing the Christian message in their native languages: rhyfeddai y lliaws . . . , gan ddywedyd: Pa fodd yr ydym yn eu clywed bob un yn ein hiaith ein hun, yn yr hon i’n ganed ni? (‘the masses were amazed . . . , saying: “How can we each one hear them in our own languages, in which we were born?’).

The concept of being born in or to a language emphasizes the importance of the mother tongue; this essay is ensuring that Welsh readers are aware of the momentous fact that they are now holding a bible in their mother tongue in their own hands.

Affordable

While acknowledging the fact that the Bible had already been printed in Welsh, the anonymous author lingers over the difference between the earlier publications and this new, smaller and more affordable one:

Canys (ac yntau wedi ei brintio a’i rwymmo mewn Folum fawr o bris vchel) ni ellid cen hawsed na’i ddanfon ar led, na’i gywain i dai a dwylaw neilltuol, eithr yr oedd efe gan mwyaf yn hollawl yn perthyn i Liturgi a gwasanaeth yr Eglwys, fel yr oeddyd hefyd wedi ei amcanu ef yn bennaf ar y cyntaf.

‘Thus (as it was printed and bound in a big Volume costing a high price) it was not so easy to send out, nor to carry it to various houses and hands, but rather it belonged for the most part to the Church’s Liturgy and service, as indeed it had been chiefly intended from the outset.’

Personifying the new more affordable Bible as a friend, readers are encouraged to take it – or ‘him’ – to live with them in their own homes. Using a witty comparison, the writer contrasts a person you might greet in passing at church with a friend whom you treat as a member of your own family:

Ni wasanaetha yn unig ei adel ef yn yr Eglwys, fel gŵr dieuthr, ond mae’n rhaid iddo drigo yn dy stafell di, tan dy gronglwyd dy hun. Ni wasanaetha i ti ei gyfarch ef bob wythnos, neu bob mis, mal yr wyt ti ond odid yn arfer o gyrchu i r Eglwys; ond mae’n rhaid iddo ef drigo gyda’th ti fel cyfaill yn bwytta o’th fara, fel anwyl-ddyn a phen-cyngor it.

‘It will not serve to simply leave him in the Church, like a stranger, but rather he must reside in your room, beneath your own roof. It will not serve for you to greet him every week, or every month, as you do as if by habit while going to Church; but rather he must reside with you as a friend eating of your bread, as a dear person and chief advisor to you.’

Authority

Remembering the connection between the 1567 New Testament with Bishop Richard Davies, Bishop William Morgan’s work on the 1588 Bible, and the association of the 1620 Bible with Bishop Richard Parry, it is important to note that the main energy and authority driving Welsh translations of the Bible stemmed from the heart of the Anglican establishment.

However there is something about this piece of original prose published with the 1630 Beibl Bach which suggests that a (proto-)Puritan was at work. Describing the authoritative church Bible as gŵr dieithr – ‘a strange man’, ‘a foreign man’ or ‘a stranger’ – might have shocked some conservative Anglicans.

A few years ago, I was working on a novel which had me imagining the milestones in the life of a seventeenth-century Welsh Puritan. One chapter I knew I had to write was set in the year 1630 and centres on the appearance of the Beibl Bach in the protagonist’s home. Whether dealing in fact or fiction, it is difficult to imagine the course of so many seventeenth-century Welsh lives without taking this milestone into account.

Further Reading:

Ceri Davies (ed.), Dr. John Davies of Mallwyd: Welsh Renaissance Scholar (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1998).

See the chapter ‘1630’ in Jerry Hunter, Dark Territory, translated by Patrick K. Ford (Y Lolfa, 2017), or, in the Welsh original, Y Fro Dywyll (Y Lolfa, 2014).

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.