Yr Hen Iaith part forty-one: A Manifesto for the Language – William Salesbury’s Introduction to Oll Synnwyr Pen

We continue the history of Welsh literature as Jerry Hunter guides fellow academic Richard Wyn Jones through the centuries in a series of lively podcasts. This article complements episode 41.

A chymerwch hyn yn lle rhybudd y gennyf fi: onid achubwch chwi a chyweirio a pherffeithio’r iaith cyn darfod am y to ysydd heddiw, y bydd rhy hwyr y gwaith gwedy.

‘And take this as a warning from me: if you do not save and repair and perfect the language before today’s generation passes away, it will then be too late to do the work.’

Jerry Hunter

William Salesbury published these words in 1547. He is telling readers in stark terms that will soon be too late if they don’t ‘save’ (achub) the Welsh language immediately.

Was he an overreacting alarmist? It’s impossible to know for sure; the project in which Salesbury and other Welsh humanists were engaged succeeded in ‘repairing’ (cyweirio) and ‘perfecting’ (perffeithio) the language, and it would take a lot of linguistic guesswork to write an alternative history of Welsh in which these sixteenth-century interventions did not take place.

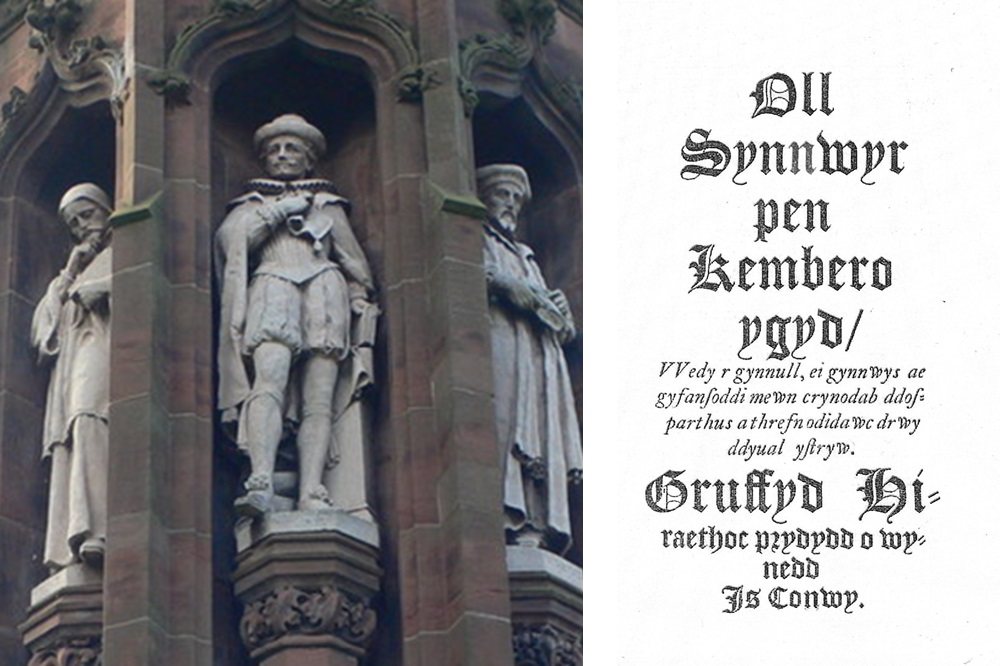

Salesbury’s passionate plea is found in his introduction to a collection of proverbs compiled by the professional bard Gruffudd Hiraethog.

The book’s long title makes this clear: Oll Synnwyr Pen Cymro ynghyd, wedi’i gynnull, ei gynnwys a’i gyfansoddi mewn crynodeb ddosparthus a threfn odidog drwy ddyfal ystryw Gruffydd Hiraethog, prydydd o Wynedd Is Conwy (‘All of the Senses of a Welshman’s head together, collected, included and arranged in an orderly compendium and splendid arrangement through the diligent industriousness of Gruffudd Hiraethog, poet of Gwynedd Is Conwy’).

In William Salesbury and Gruffudd Hiraethog we have an example of a positive and constructive relationship between a university-educated humanist and a traditional bard (more on this in the next episode).

And in Oll Synnwyr Pen we have a book which repackages the kind of proverb collections found in medieval manuscripts for a new kind of readership in a new age.

While there is much to say about this intriguing combination of the old and new, we’ll focus here on a few aspects of Salesbury’s introduction.

Literary artistry

In terms of literary artistry, this text is perhaps the most memorable work by the Oxford-educated humanist.

Salesbury opens his introduction with an engaging description of the book’s history. He does this in an extremely playful way, telling us that it was ‘while kind of shuffling quickly’ (Wrth ryw drawsdreiglo disymwth) through his ‘rather idle manuscripts’ (llyfrau gosegur) that he came upon the collection of proverbs which he had ‘urgently copied’ (ei dear-gopio) with his own hand.

Not only is he having fun with his native language; Salesbury is also expanding its boundaries by coining new words, combining ones familiar to readers to create new compounds (trawsdreiglo, taergopio) which convey the story in a fresh, detailed, memorable and comic manner.

Continuing in this vein, Salesbury adds that it was during a trip to London with Gruffudd Hiraethog three years previously when he made this copy: Ac yno y brith-ladretais gopio hyn o ddiarhebion (‘And it was there that I kind-of stole a copy of these proverbs’).

The word lladrata, ‘to steal’, is combined with brith to it, thus creating a new word, brith-ladrata, ‘kind-of stealing’ or ‘partly-stealing’, which he conjugates in the past tense (brith-ladretais, ‘I kind-of stole’).

This is a writer who is enriching the Welsh language as he writes, playfully extending the bounds of its vocabulary and introducing new turns of phrase.

Playfulness

This linguistic playfulness is then used as a mechanism for delivering a very serious point. Just as he ‘kind-of stole’ the contents of Gruffudd Hiraethog’s manuscript, William Salesbury wishes that all existing Welsh manuscripts ‘had been stolen in that manner’ (wedi’r lladrata o’r modd hynny).

As has been stressed already in this series, it was three interconnected factors – the Protestant Reformation, humanism and the printing press – which ensured that the first Welsh books were printed.

Fueled by Protestant zeal as well as the humanist’s attention to language, William Salesbury was urging people to use the printing press and create new books out of the contents of old manuscripts.

He chastised owners of manuscripts who weren’t sharing these literary treasures with other Welsh people: I ba beth y gedwch i’ch llyfrau lwydo mewh conglau, a phryfedu mewn cistiau, a’u darguddio rhag gweled o neb, onid chwychwi eich hunain? (‘Why do you keep your manuscripts mouldering in corners and being eaten by worms in chests, and [why do you] hide them so that nobody except yourselves see them?’).

Linguistic and literary treasures

In addition to coining new words and creating new turns of phrase – as Salesbury did himself, powered by his study of classical languages and their literatures – this humanist wanted to ensure that Welsh linguistic and literary treasures from the past were available to revitalize the language in the present.

His introduction to Oll Synnwyr Pen is nothing less than a Welsh humanist’s linguistic manifesto.

He sought to ensure that his native language would be a medium capable of treating all kinds of dysg, ‘learning’, but it was religious learning which was of paramount importance to this Protestant humanist; he tells readers that, if Welsh were to be revitalized in this way, ‘it would be easier for a Welshman to understand the preacher while preaching God’s word’ (Ac fe fyddai haws i Gymro ddeall y pregethwr, wrth bregethu gair Duw).

And the very foundations of religious instruction would be transformed, for it would also ‘be much easier for the preacher to discuss God’s word intelligently’ (Fe fyddai haws o lawer i’r pregethwr draethu gair Duw yn ddeallus).

Registers

Linguists today talk about ‘registers’, the varieties of a language used in specific situations or for specific purposes.

William Salesbury tells his 1547 readers in characteristically passionate terms that the language they use for everyday activities is not suitable for treating all possible aspects of human thought and culture:

A ydych chwi yn tybied nad rhaid amgenach eiriau, ac i adrodd athrawiaeth a chelfyddydau, nag sydd gennych chwi yn arferedig wrth siarad beunydd yn prynu a gwerthu a bwyta ac yfed? Ac od ych chwi yn tybied hynny fo’ch twyller.

‘Do you suppose that different words are not needed for relating learning and the arts than the ones you use when talking every day while buying and selling and eating and drinking? And if you do suppose that, you are deceived.’

His words form a rhetorical whip, stinging complacent readers and impelling them to take action.

Passionately urgent

While Welsh had been a language of learning since at least the Old Welsh period, society and circumstances had changed drastically and things had to be done to ensure that it would be a language of learning in the future.

It is easy to understand why William Salesbury adopted such a passionately urgent authorial voice.

In the 1970s, protestors were willing to go to great lengths to ensure the creation of a Welsh television station; Gwynfor Evans went on a hunger strike, members of Cymdeithas yr Iaith climbed television masts, and many other actions were taken.

Television was the medium of the new age, and people who felt passionately about the future of the Welsh language new that it had to have access to that medium.

Print was the newest medium in the sixteenth century and William Salesbury was urging other Welsh people to use that information technology to revitalize the language.

It’s difficult to imagine what the state of Welsh would be if Salesbury and others didn’t pursue that agenda successfully.

Further reading:

- Brinley Jones, William Salesbury (1994).

Catch up with all the previous episodes in this series here

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Gwych