Yr Hen Iaith part one: Y Gododdin

In the beginning was the Gododdin (or was it?)

To accompany episode 1 of Yr Hen Iaith (‘the Old Language’) podcast, one of its co-hosts, Professor Jerry Hunter of Bangor University, traces the history of Welsh literature back to its earliest roots, being a tragic account of a band of soldiers who lost their lives on the field of battle.

Jerry Hunter

‘What is the earliest Welsh-language literary text?’ When I posed that question to my old friend Richard Wyn Jones, he answered in a way which will come as no surprise to many Welsh people: Y Gododdin. If our podcast took the form of a straight-forward series of academic lectures on the history of Welsh literature, I would’ve started in a different way, focussing on the earliest evidence of Welsh writing (spoiler alert: I’ll do my best to get some of that into next week’s episode).

However, Yr Hen Iaith is a dialogue between two friends, not a lecture, and we began with Richard’s answer to my question. We began with the Gododdin. However, I had to risk disappointing my friend straight away by telling him that this is, in fact, an extremely complicated question and that the Gododdin both is and isn’t the earliest surviving Welsh-language text.

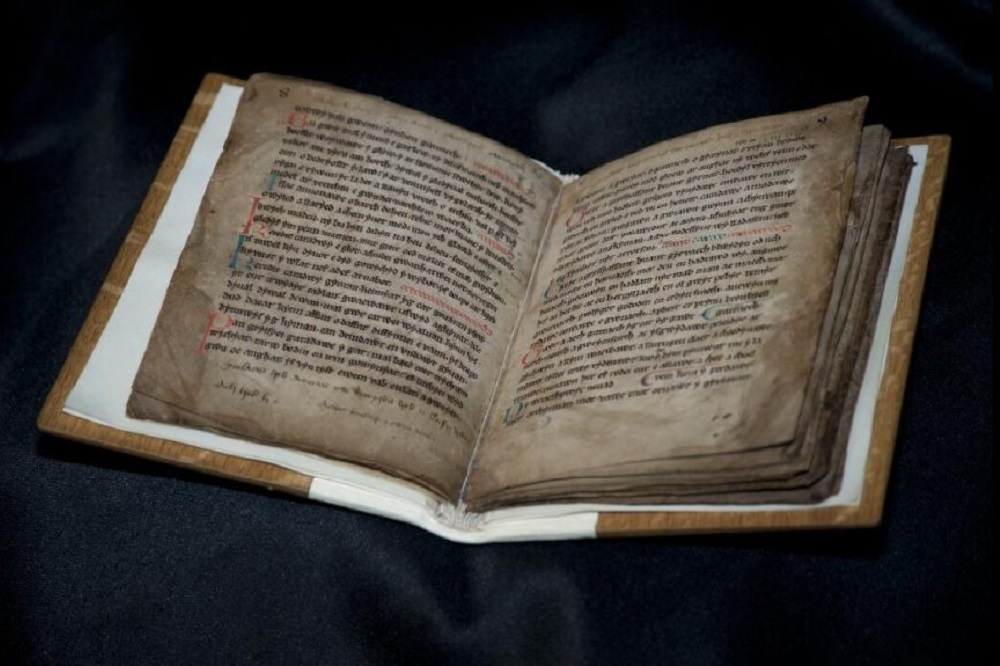

What we can say for certain is that Y Gododdin is a body of poetry, perhaps best described as a series of connected poems elegizing warriors who died in battle at Catraeth. This poetry is contained in a medieval manuscript – known now as Llyfr Aneirin, The Book of Aneirin – written during the second half of the 13th century, most likely at a Welsh Cistercian monastery (for example, at Aberconwy, Strata Marcella or Strata Florida).

There are two copies (or ‘texts’) of Y Gododdin in the manuscript, written by two different copyists (or ‘hands’). It appears that they were copying different, older versions, and thus it is certain that this body of poetry is older than the date of the Book of Aneirin itself. Indeed, Aneirin (or ‘Neirin’), to whom the Gododdin is attributed, is listed in the 9th-century Latin text, Historia Brittonum, as one of five famous poets who lived in the 6th century.

It is difficult and perhaps impossible to determine just how old this poetry is. The Book of Aneirin belongs to the period in the history of the language known as Middle Welsh, beginning c.1150 and ending in the 16th century (let’s use the publication of William Morgan’s Bible in 1588 as a useful benchmark for the sart of Modern literary Welsh).

The period from c.750 to c.1150 is describe as that of Old Welsh, and there are linguistic forms in the Gododdin which suggest an origin in this period. Scholars such as John Koch had used linguistic methodologies to suggest that some of this poetry is even older than the Old Welsh period.

Other scholars disagree, and this is one of many areas in Welsh scholarship which is the focus of often heated debate. The answer to the question ‘how old is Y Gododdin?’ depends on which scholars you believe and which parts of the evidence you chose to highlight. Perhaps a more nuanced answer would be to say that the Gododdin has many linguistic layers and thus, in a sense, many ages.

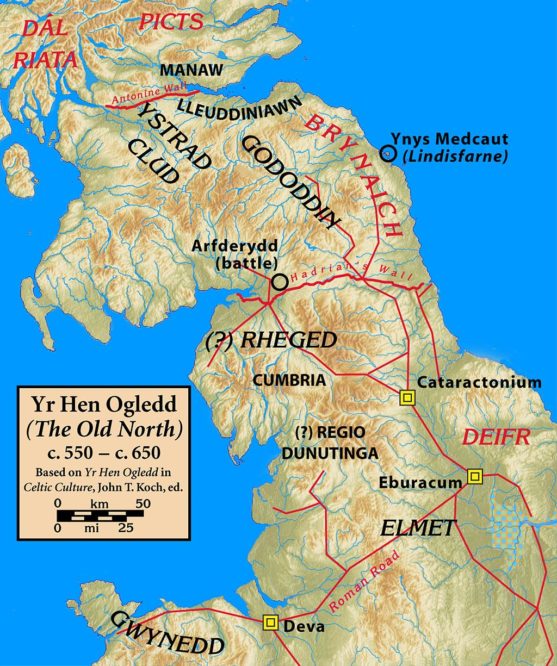

The name Gododdin (recorded in Latin as Votadini) refers to a group of people, which we might think of as a ‘tribe’, but also as a way of connecting people to specific lands and the socio-political structures governing them. These were some of the British Celts who spoke Brythonic (the direct ancestor of the Welsh language) inhabiting Yr Hen Ogledd, ‘the Old North’, a region which is now in southern Scotland and northern England. (This is why the famous Celticist Kenneth Jackson described Y Gododdin as ‘the Oldest Scottish Poem’.)

The lands of the Gododdin including what is now Edinburgh, were referred to in this poetry as Dineidin. After feasting at length on glasfedd, ‘fresh mead’, the Gododdin warriors attacked the enemy at Catraeth, identified with Catterick in Yorkshire, where most of them died. The enemy, the Angles of Deira, are described in the poetry as Lloegrwys, ‘men of England’, and Saeson, ‘English’ or ‘Saxons.’

Y Gododdin has thus been seen as the first text in a long literary tradition focussing on warfare between the Welsh and the English. Once again, historical reality might have been much more complicated; there might have been Brythonic-speaking ‘Celts’ and Germanic-speaking ‘Angle-Saxons’ fighting in both armies. Many scholars put the battle of Catraeth (or Catterick) at around the year 600 (some have suggested slightly earlier dates).

In one of the two versions found in the Book of Aneirin, the first lines suggest a performative context:

Gododdin, gofynnaf o’th blegyd / Yng ngŵydd cant yn arial yn emwyd (‘Gododdin, I make claim on thy behalf / In the presence of the throng boldly in the court’).*

The other version begins with one of many stanzas commemorating the heroism of a fallen warrior. The first line – easily understood by Welsh speakers today, once the orthography or spelling is modernized – is beautiful in its simplicity:

Greddf gŵr, oed gwas (‘A man’s nature, a youth’s age’).**

It is a powerfully concise way of staying, straight-away that this warrior fought like a man even though he was only a lad. The word gŵr, ‘man’, might also be taken as meaning ‘warrior’. The plural form (gwŷr, ‘men’) begins a phrase which introduces many of the Gododdin’s stanzas: Gwŷr a aeth Gatraeth, ‘men (or ‘warriors’) went to Catraeth’.

I have been telling Richard for several decades that he should learn more about Welsh literature, and his decision to finally do this is what led to this podcast. Yet, even though he states repeatedly during our conversations that he is embarrassed by his lack of knowledge, Richard was able to quote a few lines of Y Gododdin from memory:

‘Gwŷr a aeth Gataeth, oedd ffraeth eu llu, / Glasfedd eu hancwyn a gwenwyn fu (‘Warriors went to Catraeth, their host was swift, / Fresh mead was their feast and it was bitter’).***

It is memorable poetry, contrasting the energy of life with the stillness of death, the feasting beforehand with the battle’s bloody end. Translated here as ‘bitter’, gwenwyn can also mean ‘poison’, suggesting that the heroic drink which nourished them also led to these warriors’ deaths and that the aftertaste, at least for the poet, is indeed ‘bitter.’

Original copy is kept at Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru | The National Library of Wales and can be viewed here

Further reading (in addition to the edition and translation by A. O. H. Jarman noted below):

John T. Koch, The Gododdin of Aneirin: Text and Context from Dark-Age North Britain (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1997).

Kenneth H. Jackson, The Gododdin: The Oldest Scottish Poem (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1969).

See also Patrick Sims-Williams, ‘Dating the Poems of Aneirin and Taliesin, Zeitschrift für Celtische Philologie 63 (2016), 163-234.

For an English adaptation by a contemporary poet, see Gillian Clarke’s Lament for the Fallen.

* Quoted from: A. O. H. Jarman (editor and translator), Aneirin: Y Gododdin [:] Britain’s Oldest Heroic Poem (Llandysul: Gomer, 1990), pages 1-2.

** Jarman, Aneirin: Y Gododdin, pages 1-2.

*** Jarman, Aneirin: Y Gododdin, pages 6-7.

Find out more about the podcast here

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Very interesting reading. Those living in Hen Ogledd (Old North) called themselves Cymry hence place names in now Northern England with Cumbria & Southern Central Scotland like Cumbernauld, Cumnock, Cumberland etc… Written in Welsh manuscripts also is a story of an exiled Welsh king who fled North to Rhedeg and wrote how he was welcomed by cheering crowds who spoke his language and he noted how it felt like being his own country. Also, it’s been said that people from Manaw Gododdin settled and founded the kingdom of Gwynedd with Cunedda son of King Coel hence the story & legend… Read more »

And then the Descendants of Cunedda had a hand in the usurpation of the throne of the Britons that rightfully belonged to the House of Bran in South Wales….this is the true origins of The White vs Red Dragon story… it was in fact based on the constant rivalry between The house of Aberffraw (Red) and the House of Bran (White). Wessex initially sided with The house of Bran, but would eventually go onto to support Aberffraw. The House of Bran, and indeed Britains last rightful heir was Iestyn Ap Gwrgan, who passed in the 11th century.