Yr Hen Iaith part six: Manawydan and the Foundations of Society

Continuing our series of articles to accompany the podcast series Yr Hen Iaith. This is episode six.

Jerry Hunter

Richard Wyn Jones made an excellent observation as we discussed the tale of ‘Manawydan son of Llŷr’: this, Third Branch of the Mabinogi, seems to be less known than the other Branches in Wales today. I am sure that he is correct.

Branwen’s tale has been used as a frame for recent meditations on war, and the story of Blodeuwedd has inspired many modern writers – and provided material for numerous school plays and pageants.

As Richard also pointed out, this is perhaps ironic, because the tale of Manawydan might be described as the most modern of the Four Branches and the one most relevant to us today.

Meditations

It provides a striking counterpoint to the other Branches, and it is also driven by meaningful internal contrasts. Instead of tragic epic battles, this tale presents meditations on the foundations of society and the essence of civilization.

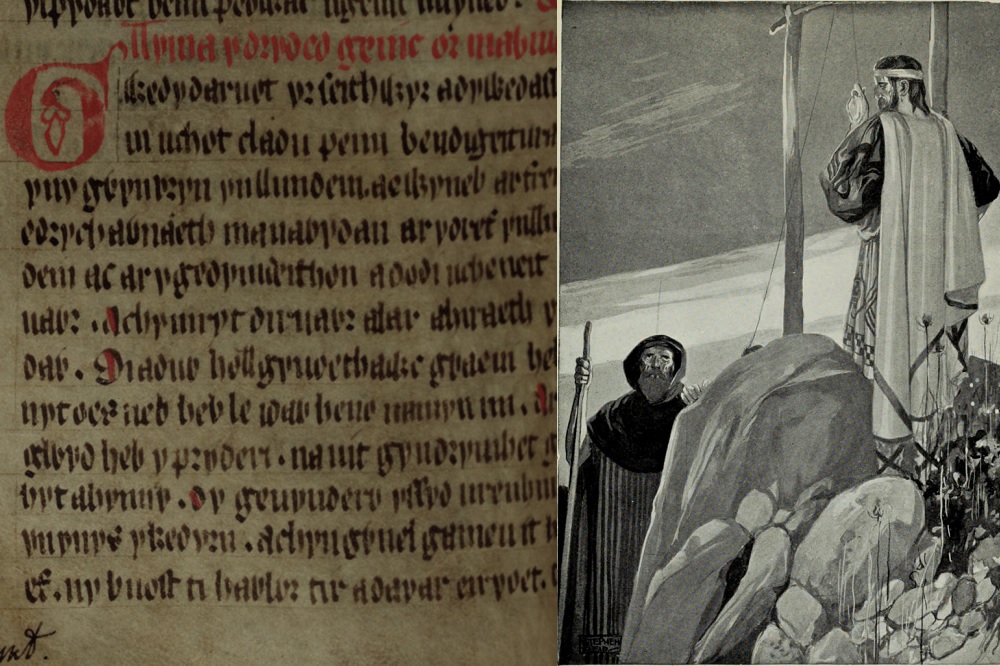

It is also essential for understanding that the Four Branches of the Mabinogi form a coherent whole. Indeed, the text’s opening sentence presents it overtly as a sequel to the proceeding Branch:

Guedy daruot y’r seithwyr a dywedyssam ni uchot; cladu penn Bendigeiduran yn y Gwynuryn yn Llundein, a’y wyneb ar Freinc, edrych a wnaeth Manauydan ar y dref yn Llundein, ac ar y gymdeithon, a dodi ucheneit uawr, a chymryd diruawr alar a hiraeth yndaw.

‘After the seven men we spoke of above buried Bendigeidfran’s head in the White Hill in London with his face towards France, Manawydan looked at the town of London, and at his companions, gave a great sigh, and was filled with immense grief and longing.’

Artistry

While obviously drawing upon traditional material, this is a work of literary artistry, and while we can assume that a great deal of those earlier traditions were transmitted orally, this text belongs inextricably to a literate culture.

Consider that simple word in this opening sentence, uchod (‘above’); it does not remind listeners of a tale told earlier but rather directs the eyes of readers back through the manuscript which they hold in their hands.

Indeed, reading this Branch against the ones coming before and after intensifies its memorable message. While the other three Branches contain a considerable amount of bloodshed, and while the threat of violence looms large in this tale, it is always avoided by Manawydan, who consistently seeks a different path.

Following the death of his family in the previous Branch, Manawydan is bereft and without a home. Pryderi takes him in, and Manawydan becomes a literal part of his friend’s family when he marries Pryderi’s widowed mother, Rhiannon.

They rule Dyfed together until an enchantment falls, removing all except for the tight-knit family unit, including as its fourth member Pryderi’s wife, Cigfa.

The four transition from one kind of existence to another, first living simply off of the land; they ‘hunt’ (hela), getting their ‘sustenance’ (ymborth) from ‘meat [gained by] hunting’ (kic hela), ‘and fish and [honey from] bee hives’ (a physcawt a bydaueu).

Enchanted

They eventually grow tired of life as hunters and gatherers, and trade the enchanted wilderness in western Wales for a very mundane existence in England, working as craftsmen in Hereford (Henffordd).

They fashion parts for saddles, and because Manawydan is extremely skilled at this, they succeed and local competitors rise up against them.

An embodiment of the warlike society depicted in the first two Branches, Pryderi wants to fight, confident that they can easily kill these tayogeu or ‘peasants’, but Manawydan insists that they avoid conflict by moving to another English town instead.

The pattern is repeated, as they then fashion shields and, finally, shoes, after relocating yet again for the same reason. They then return to Dyfed, and Pryderi rushes rashly into a magical trap, followed by his mother Rhiannon.

Manawydan then turns to agriculture for support, but must overcome yet another obstacle when the crops are stolen. After catching one of the culprits, he is determined to follow the law and hang the thief, a course of action which leads to the lifting of the enchantment and the restoration of Pryderi and Rhiannon.

Contrast

The story’s tapestry includes a look at the civilization’s material foundations – earning food by exploiting nature, developing crafts and agriculture – while also providing a striking contrast between Pryderi’s warrior ethos and Manawydan’s avoidance of conflict.

Manawydan is heroic and ultimately triumphs, not because of external strength but because of his wisdom and internal strength.

As was noted in episode four of this podcast, rather than viewing the Four Branches as reflexes of long-lost ‘Celtic mythology’, I prefer to read them as literature reflecting the medieval Welsh society of which they were a part.

Rather than performing linguistic gymnastics in order to regress character names to the monikers of pre-Christian deities, it makes more sense to find signposts to meaning in proper nouns (that is, names) which are easily related to common nouns.

Remember that Pwyll, the central character in the First Branch, has a name meaning pwyll, ‘sense’.

Meat

Many years ago, Ian Hughes suggested to me that we read Manawydan’s name in the context of the common noun, mynawyd, meaning ‘awl’. Indeed, that tool, used for working leather, is a concise way of indexing Manawydan’ success as a craftsman and his desire to follow peaceful enterprise instead of violence.

It is also worth noting that the name of Pryderi’s wife, Cigfa, is also a common noun, cigfa, meaning ‘a place where meat is procured’.

As this name doesn’t appear elsewhere in medieval Welsh literature to my knowledge, it was surely a clever choice made by our author in order to highlight the fact that, when trying to build up society again from scratch, these characters must being simply, living on cig hela, or ‘meat [gained by] hunting.’

This tale depicts characters rebuilding their lives in the wake of war, following Manawydan’s lead – often reluctantly – and creating a society defined by peaceful pursuits and the rule of law.

It is not external strength which makes Manawydan a hero, but rather his wisdom and his internal strength.

Further Reading:

Andrew Welsh, ‘Manawydan fab Llŷr: Wales, England and the “New Man”’, yn C. W. Sullivan III (ed.), The Maginogi[:] A Book of Essays (Routledge, 2016)

Ian Hughes (ed.), Manawydan uab Llyr: trydedd gainc y Mabinogi: golygiad newydd ynghyd â nodiadau testunol a geirfa lawn (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2007)

Gwyn Jones and Thomas Jones (translators), The Mabinogion (revised edition, London, 1993)

Patrick K. Ford, The Mabinogi and Other Medieval Welsh Tales (new edition, 2008)

Sioned Davies (translator), The Mabinogion (Oxford: OUP, 2008)

You can catch up with the previous episodes here

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Diddirol, diolch