Yr Hen Iaith part ten: Voicing Loss – The Songs of Heledd

Jerry Hunter

Continuing our series of articles to accompany the podcast series Yr Hen Iaith. This is episode ten.

The Songs of Heledd

Medieval Welsh poetry is dominated by men. Male poets sing praises to kings or princes. The bloody feats and heroic deaths of masculine warriors are celebrated.

Prophetic bards tell of the coming of y mab darogan, ‘the son of prophecy’ who will deliver the Welsh nation from its enemies. And most surviving love poetry from the medieval period presents men’s desires (with attendant constructions of an objectified female ideal).

Remembering that Welsh poets are commonly described as ‘singing’ (canu) their compositions, we might think of the bulk of Welsh poetry surviving in medieval manuscripts as a deafening chorus of male voices.

The voice of Heledd cuts through this resounding male cacophony. Even if the poetry connected with her wasn’t the powerful and beautiful verse which it is, this body of work would be important because of its representation of a female voice.

Mourning a lost Welsh kingdom

Canu Heledd, the poetry ‘sung’ in the voice of Heledd, is preserved in the Red Book of Hergest (c.1400).

Linguistic evidence suggests that it was composed earlier – perhaps much earlier – than the date of the manuscript (although the exact date of composition is not easy to settle and too complex to be discussed here).

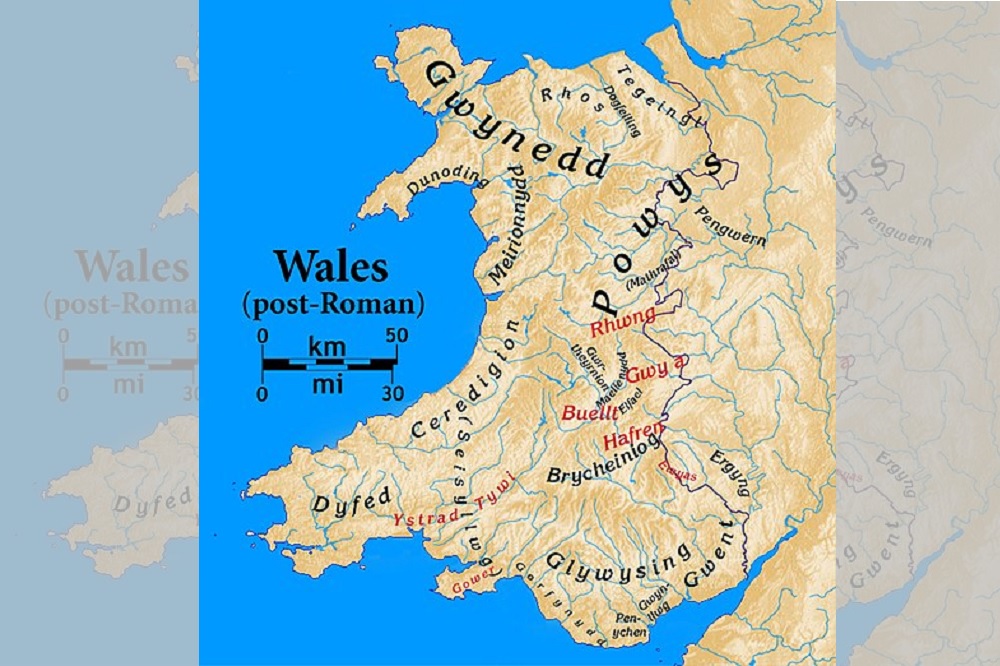

Heledd is presented as a princess from Powys – the old kingdom of Powys, much of which now lies over the border in England.

Ifor Williams suggested that this poetry deals with events from seventh century seen through the lens of the ninth century. Jenny Rowland, a scholar who has written more than anybody else about this literature, proposed a different time frame.

All debates about historical foundations aside, what is important from a literary point of view is that this is medieval Welsh poetry which mourns a lost Welsh kingdom. And that mourning is presented from a woman’s point of view.

All poets are men

These poems are anonymous. They are presented dramatically as verses uttered by the character Heledd, but we don’t know the name of the poet – or poets – who actually composed these lines.

The earliest body of Welsh poetry composed by a woman dates from the second half of the fifteenth century (and this will be the subject of a later episode!). All poets named in Welsh manuscripts prior to that time are men.

Does that mean that Heledd’s ‘songs’ are in fact composed by a male bard? The history of literacy in Wales leads us to suspect that, but the singularly powerful nature of Heledd’s voice provides at least some room for speculation.

It is tempting to imagine the poetry recorded in the Red Book of Hergest being performed by a woman of the court. It might also reflect lost traditions in which women played a leading role in mourning the dead.

We simply don’t know, but we do have Heledd’s voice and we can rejoice in the fact that this female voice is a powerful and lasting literary creation.

Destruction

Like Canu Llywarch Hen, the poetry ‘sung’ in the voice of Llywarch Hen, Canu Heledd is sometimes described as ‘saga englynion’.

These poems consist of one or more three- or four-line englynion, that compact strict-metre Welsh verse form so well suited to epigram and epitaph.

The word ‘saga’ is used because of this poetry’s apparent association with narratives. There is the story of Llywarch, old and alone, his many sons killed fighting the enemy.

And there is the story of Heledd, wandering, alone, mourning the death of her family and the destruction of the kingdom once ruled by her brother, Cynddylan.

However, the term ‘saga’ is grafted onto this literature, and is perhaps misleading in its Norse origins. It is best to say that this poetry is associated with narrative.

That does not mean that this is narrative verse or poetry which ‘tells a tale’ in detail. The poems sung attributed to Heledd focus on her emotional reaction to events and circumstances.

Like a good modern pop song, a few lines are used to inspire the listener (or reader) to imagine the story lurking behind these sparse but well-placed words.

Consider, for example, the way in which this englyn introduces Heledd’s voice to us:

Sefwch allan, forynion, a syllwch

Gynddylan werydre:

Llys Bengwern neud tandde.

Gwae ieuaingc a eiddun brodre.

‘Stand out, maidens, and look

at Cynddylan’s land:

The court of Pengwern is burning,

Woe the young people who seek a cloak.’

Calamitous moment

Interestingly, like the speaker/singer, the listeners are female. One grammatical detail, the mutation of the first letter of the word morynion, ‘maidens’ – turning it into forynion – emphasizes the fact that Heledd is addressing these other women directly.

We are caught up in the dramatic present of a calamitous moment, the utter destruction of their society happening before our eyes as king Cynddylan’s court at Pengwern burns, and we see this through entirely female eyes.

In other poems Heledd is bereft of the female company watching the burning court with her.

Alone, she wanders through the ruined kingdom, contemplating a loss which is personal, political and cultural.

One of the most powerful englynion of the series has us imagining her looking at the ruins of her brother’s kingly hall.

Stafell Gynddylan ys tywyll heno,

Heb dân, heb wely;

Wylaf wers, tawaf wedy.

‘Cynddylan’s hall is dark tonight,

Without fire, without bed;

I will cry for a while, I’ll be silent afterwards.’

Given the way in which these compact lines present such a memorable expression of loss and longing, it’s no surprise that later writers have echoed Heledd’s voice, from Kate Robert’s 1962 novella, Tywyll Heno (‘Dark Tonight’) to Angharad Tomos’s 2007 novel Wrth fy Nagrau i (‘By my Tears’).

A notable milestone in the history of Welsh popular music, Tecwyn Ifan’s 1977 album, Y Dref Wen (‘The Blessed Town’), was also inspired by this body of medieval poetry.

Emotional blow

The first englyn in the poem mourning the destruction of the ‘Blessed Town’ provides another devastating emotional blow:

Y dref wen ym mron y coed,

Ysef ei hefras erioed,

Ar wyneb ei gwellt y gwaed.

‘The blessed town by the woods,

Thus was always its custom,

[but now] on its grass [there is] the blood.’

Slaughter

The final word, gwaed, ‘blood’, provides a horrific ending, abruptly displacing the memory of the peaceful community that had always thrived in this place with the image of its slaughtered inhabitants.

There are lines which contrast Heledd’s present condition with her past, saying that she now wears a hard goat-skin coat rather than a mantel fit for a princess, and that she – who once feasted on mead in her brother’s court – now wanders homeless.

She lists the names of deceased family members; in addition to Cynddylan, she has lost her brothers Cynan and Cynwraith, all killed ‘ar unwaith’, ‘at the same time.’

The list of her dead sisters provides a record of medieval Welsh women’s names: Gwladus, Gwenddwyn, Ffreuer, Meddwyl, Meddlan, Gwledyr, Meisir and Ceinfryd.

It is interesting that only one of these eight names, Gwladus or Gwladys, has had anything like currency in a period remotely close to own.

The name Heledd, however, has been used often enough during recent decades. This is further testimony to the impact of this literature on Welsh thinking well beyond the medieval period.

Further Reading:

Jenny Rowland, Early Welsh Saga Poetry: A Study and Edition of the Englynion (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1990).

You can catch up with the previous episodes here

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

It was a wise move by Jerry,getting Richard to read the verse,his ‘llond ceg’ Venedotian is more suited to it than Jerry’s rather flat Mid-Western tone.