Yr Hen Iaith part thirteen: Winning Olwen

Jerry Hunter

Continuing our series of articles to accompany the podcast series Yr Hen Iaith. This is episode thirteen.

When Culhwch finally sees Olwen for the first time, we, the readers, are treated to a memorable description of her.

She is wearing ‘a gown of flame-red silk’ (camse sidan flamgoch) and ‘a neck-torque of red gold’ (gordtorch rudeur) with ‘valuable pearls and rubies in it’ (mererit gwerthuawr yndi a rud gemmeu).

The hair of her head was ‘yellower . . . than flowers of the broom’ (melynach . . . no blodau y banadyl), and ‘her cheeks were redder than the rose [or foxglove]’ (oed kochach y deu rud no’r fion).

Not only is her likeness described by referencing flowers; she leaves a living floral path in her wake: Pedeir meillionen gwynnyon a dyuei yn y hol yn yd elhei. Ac am hynny y gelwit hi Olwen. (‘Four white clover grew in her tracks wherever she went. And because of that she was called Olwen.’ [ôl wen = ‘white track’])

Super powers

Getting to this point was no mean feat, and Culhwch didn’t do it alone. As his cousin Arthur’s messengers could not discover anything about Olwen, the great leader then called upon six of his most famous heroes to go with Culhwch on this quest, first and foremost of whom are Cai and Bedwyr, who feature in other Welsh Arthurian texts.

Each hero has his own unique qualities (or ‘super powers’, as Richard Wyn Jones would have it, in reference to popular contemporary film).

Indeed, together with Culhwch they form an elite band of seven adventures, a medieval Welsh precursor to films such as ‘The Seven Samauri’ and ‘The Magnificent Seven’.

Monstrosity

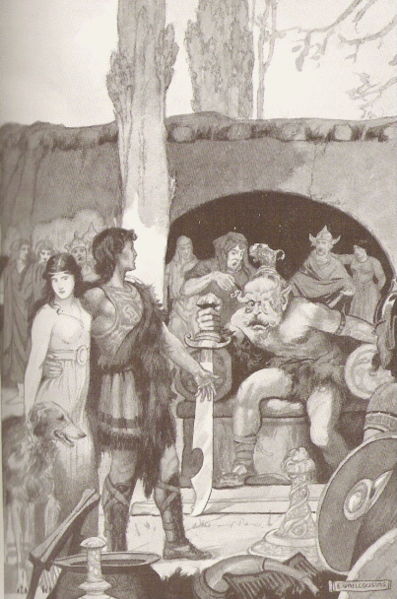

However, finding Olwen is the easy part. She must be won, and her father – Ysbaddaden Pencwar (or ‘Chief Giant’) is a fearsome opponent.

The relationship between Culhwch and Ysbaddaden can be seen as a fanciful and extreme portrayal of a young man’s fear of his future father-in-law (this giant will try to kill him) and a father’s fear that his son-in-law will displace him (Olwen says that her father will die if she marries).

When the heroes first gain entry to the Chief Giant’s fortress – after slaying the nine gatekeepers and nine guard dogs without making a sound – they greet Ysbaddaden in the name ‘of God and of man’, ‘o Duw ac o dyn’, incidentally reminding us that, however fantastical this world may be, we are still in a Christian context.

When they see the giant, a grotesquely humorous part of his monstrosity is revealed when he, in turn, seeks to see them:

‘Mae uy gweision drwc a’m direidyeit?’ heb ynteu. ‘Drycheuwch y fyrch y dan uyn deu amrant hyd pan welwyf defnyd uyn daw.’

‘Where are my bad servants and wretched ones?’ he said. ‘Raise the forks under my two eyelids so that I may see the substance of my son-in-law.’

The giant says that Culhwch will be allowed to marry Olwen . . . if he first accomplishes forty extremely difficult tasks, all purportedly designed to make preparations for the wedding day but obviously intended to ensure that Culhwch will die in the process.

Mini-adventures

The fulfilment of these amazing tasks or ‘anoethau’ ensures that there is a series of mini-adventures nestled within the sprawling framework of the tale.

Many of them are linked together in a narrative chain. For example, in order to prepare Ysbaddaden’s hair for the wedding day – Culhwch earlier had his hair cut by Arthur, as mentioned last week, and this kind of grooming once again seems to be a physical manifestation of the bond between two individuals – a special comb and sheers must be obtained from between the ears of the great boar, Twrch Trwyth.

It will not be possible to hunt Twrch Trwyth without first getting a particular dog, Drudwyn, and he can only be handled by using a specific leash which must also be found.

And so on, until reaching Mabon son of Modron, the only huntsman who will do when it comes to chasing down Twrch Trwyth. And Mabon disappeared when he was three nights old and nobody has seen him since.

Oldest animals

In order to find Mabon, an extra series of nestled quests not named by Ysabadden is introduced as the heroes question a series of ancient animals, each one older than the previous one, until the finally reach the oldest, the Salmon of Llyn Llyw (who does know where Mabon is imprisoned).

There is a lyric beauty to this section, and the fast-paced flow of the adventure pauses as we are compelled to meditate on the relationship between people and the natural world.

For example, when they find Cuan Cum Kawlyt, the Owl of Cwm Cawlyd, and ask after Mabon, this is the ancient bird’s answer:

‘Pan deuthum i yma gyntaf, y cwm mawr a welwch glynn coed oed, ac y deuth kenedlaeth o dynyon idaw, ac y diuawyt, ac y tyuwys yr ail coet yndaw. A’r trydydd coed yw hwnn. A minneu, neut ydynt yn gynyon boneu vy esgyll. Yr hynny hyd heddiw ni chiglef i dim o’r gwr a ouynnwch chwi.’

‘When I first came here, the big cwm you see was a wooded valley, and a tribe of men came to it, and it was destroyed, and the second wood grew in it. And this is the third wood. As for me, my wings are now only stumps. From that day until today I have not heard anything about the man you are asking about.’

History

The word cenhedlaeth, translated here as ‘tribe’, can also mean ‘generation’, and in this passage’s concise description of a wood being cut down, growing back, and being cut again and again, we have a powerful evocation of what generations of human habitation does to a land which was once a wilderness.

The boundary between animals and humans is examined – and crossed – in other ways as well in this tale, especially when the history of Twrch Trwyth and his tribe of ferocious pigs is revealed.

The seven heroes can’t do all of this themselves. In the end, Arthur himself must come – along with those many wondrous members of his court – in order to hunt Twrch Trwyth and finish fulfilling the tasks.

Indeed, on the day when Culhwch finally weds Olwen, his soon-to-die father-in-law chides him, saying that it is ‘thanks to Arthur’ (‘diolwch y Arthur’) that he has triumphed.

It is almost as if the giant is saying in a pointedly terse manners that Culhwch still isn’t good enough for his daughter because he didn’t win her by himself.

Ysbaddaden has a right to be bitter: he says this after the heroes shave his beard . . . and his skin . . . and his flesh, right to the bone. And they shave his ears off while they’re at it.

Having been utterly debased, the father is despatched once and for all; his head is cut off and placed on a stake outside. The son-in-law has indeed displaced his wife’s father, even if he didn’t do it alone.

Further Reading:

Gwyn Jones and Thomas Jones (translators), The Mabinogion (revised edition, London, 1993)

Sioned Davies (translator), The Mabinogion (Oxford: OUP, 2008)

Rachel Bromwich a D. Simon Evans (eds.), Culhwch ac Olwen (Caerdydd: Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru, 2012).

Rachel Bromwich, A. O. H. Jarman a Brynley F. Robers (Des), The Arthur of the Welsh: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval Welsh Literature (Caerdydd, 1991)

Catch up on the previous episodes here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.