Yr Hen Iaith part thirty four: A New Period?

We continue the history of Welsh literature to accompany the second series of podcasts in which Jerry Hunter guides fellow academic Richard Wyn Jones through the centuries. This is episode 34.

Jerry Hunter

Following the first series’ focus on medieval Welsh literature, this second series of Yr Hen Iaith ventures into the Early Modern Period, starting with the early sixteenth century.

First, let’s consider periodization. Why do we differentiate between medieval literature and that from the Early Modern Period? The answer lies in historical facts: Wales experience a number of changes during the first half of the sixteenth century, developments in politics, religion, technology and learning which worked together to transform society.

This was the age of the Tudors, and successive Tudor monarchs strove to strengthen royal authority and centralize power. This political drive was manifest in ‘the Acts of Union’ passed by Henry VIII’s government between 1536 and 1543, incorporating Wales within the English realm, replacing Welsh law with English law, and elevating the official status of the English language in Wales.

Religious transformation was taking place at the same time, as Henry VIII broke with Rome and made himself the supreme head of the Church in England (and thus in Wales). Originally scorned by some Welsh people as ffydd y Saeson, ‘the religion of the English’, Wales nonetheless became Protestant.

Monasteries which had been sites of literary production during the Middle Ages – and which were still offering patronage to Welsh bards during the first decades of the sixteenth century – were dissolved and these prominent architectural features of the Welsh religious landscape became ruins overnight.

Technology was changing as well, including developments in the military realm (perhaps surprisingly relevant here, as a number of important Welsh-language writers and poets from the Tudor period were professional soldiers or sailors).

The Battle of Brest in 1512 was the first European naval battle in which cannon played a significant role. However, the most important technological development in terms of its impact on Welsh-language literature was the advent of the printing press.

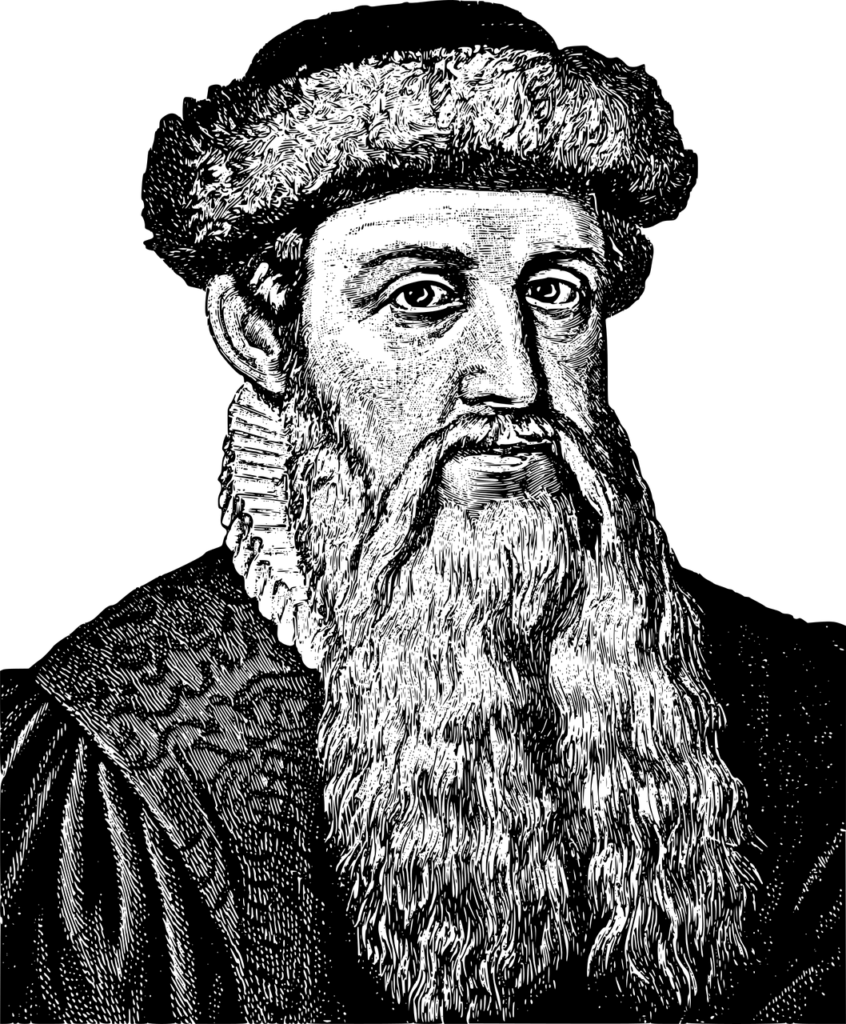

Johannes Gutenberg, working in Mainz at the middle of the fifteenth century, invented a way of printing using moveable type which then spread across Europe.

In his massive chronicle of world history, the Welsh soldier Elis Gruffydd (c.1490 – c.1555) describes the significance of the invention thus:

Dechreuwyd preintio llyfre gynta ermoed mewn dinas o Almaen, yr hon a elwir Magwns, y grefft y sydd gwedi amlhau yn fawr drwy’r holl fyd er hynny hyd heddiw. Y grefft a fu achos i bobl y byd i gaffel llawer mwy o ddysg ac o wybodaethau yn unwedig ymysg y cyffredin nog a fuasai ermoed yn y blaen.

‘Books were printed for the first time ever in a German city called Mainz, a craft which has grown greatly throughout the world between then and today. The craft has been a way for the people of the world to get much more learning and knowledge than there ever was before, especially amongst the common folk.’

Elis Gruffydd’s own writings were not published, but the first Welsh-language book was printed before the end of his lifetime. The language had only been transmitted orally or by using laboriously-fashioned manuscripts, but when Sir John Price published a short book in 1546, Welsh became a print language as well.

Many of the first printed Welsh books were produced by university-educated humanists, men who enacted their own kind of educational transformation, introducing new ideas which challenged traditional ways of viewing the Welsh language and its literature.

All of these factors worked together to drive another educational transformation, the growth of literacy. This would eventually reach sectors of the population beyond the small university-educated elite.

We take the ability to read and write for granted today, but it’s important to remember that only a very small percentage of the population in Wales (and other parts of Europe) were literate in the Middle Ages.

We are concerned here with the history of Welsh literature, and what single historical development is more important to the history of literature than the spread of literacy?

As political, religious, technological and educational developments worked together to transform society, Welsh literature had to change to meet the challenges posed by this transformation.

While there are many exciting things about Welsh writing from this period, perhaps the most obvious one is that we can see poets and writers using age-old literary forms to treat new subjects in the context of a changing world. Tradition interacted with transformation, often with surprising results.

However, we can also look at our periodization of from another angle, one which is uniquely Welsh. There is a strong argument for seeing the broad trajectory of Welsh literary history as very different from that of English, French, Italian or any other European literature.

The earliest period of Welsh-language poetry is that of the Cynfeirdd (‘The Early Poets’) or the Hengerdd (‘The Old Poetry’). Then comes that of Y Gogynfeirdd (‘The Rather Early Poets’), overlapping with the age of Beirdd y Tywysogion, ‘The Poets of the Princes’, which came to an end in 1282.

The next clear period in the history of Welsh poetry is that of Y Cywyddwyr, poets using the strict-metre cywydd form. This began during the first half of the fourteenth century and stretched to the end of the seventeenth century (and perhaps beyond, depending on how it is viewed).

The English poet Michael Drayton (1563-1631) described the relationship between his work and English literary taste with a memorable couplet: ‘my muse is rightly of the English strain / that cannot long one fashion entertain.’

Fickleness was fashionable in England; writers chased the latest trends. Among other things, it was the age of the sonnet. Welsh poets, however, did not write sonnets during the sixteenth century.

There were exceptions (and we’ll get to them in a later episode), but on the whole Welsh poets during the Tudor age did not value fickleness and the latest continental (or English) trend.

Rather than chasing the latest fashion, Welsh bards valued tradition. The cywydd and other strict-metre forms adorned by the complicated cynghanedd system continued to be central to Welsh bardic expression, as they had been for centuries

This leaves us with a big question – and it’s an interesting question as well. Should we view sixteenth-century Welsh-language literature as belonging to a new period – one defined by all of those transformative changes – or should we view it as belonging to the age of the cywyddwyr, as part of a distinct period in Welsh literary history which began back in the fourteenth century?

We should, of course, answer the question both ways, and this wonderful complexity is part of Welsh literary history’s fascinating uniqueness.

Catch up with all the previous episodes in this series here

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.