Yr Hen Iaith, part thirty nine: A Small Book and A Big Step

We continue the history of Welsh literature as Jerry Hunter guides fellow academic Richard Wyn Jones through the centuries in a series of lively podcasts. This article complements episode 39.

Jerry Hunter

Sir John Prys (or Price) earned himself a place in Welsh history by being the man responsible for the first Welsh-language book ever printed.

However, while he can be seen in this positive light as a literary creator and a technological trail-blazer who led the language into the new realm of the printed word, John Prys also helped destroy a great deal of Welsh literary culture’s traditional infrastructure.

Originally from Brecon and educated Oxford (according to one interpretation of existing records), he then followed a career in law. By the early 1530s, Prys was working for Henry VIII’s industrious servant, Thomas Cromwell.

This Welshman was responsible for some of the legal paperwork relating to the king’s break with the Roman Catholic Church.

He also played an active role in the dissolution of Welsh monasteries, helping to ensure that institutions which had been so central to Welsh religious and literary life for centuries were completely destroyed.

Like other Welsh uchelwyr, Prys benefitted by serving Cromwell and Henry VIII in this way; he gained control of land taken from monasteries, and he collected a great number of manuscripts taken from monastic libraries.

Having helped destroy the material foundations of medieval Welsh manuscript culture, he then became one of the first great manuscript collectors of the new era.

Significance

This activity also helps contextualize the book which he published in 1546, for John Prys surely took some of its contents from some of these manuscripts.

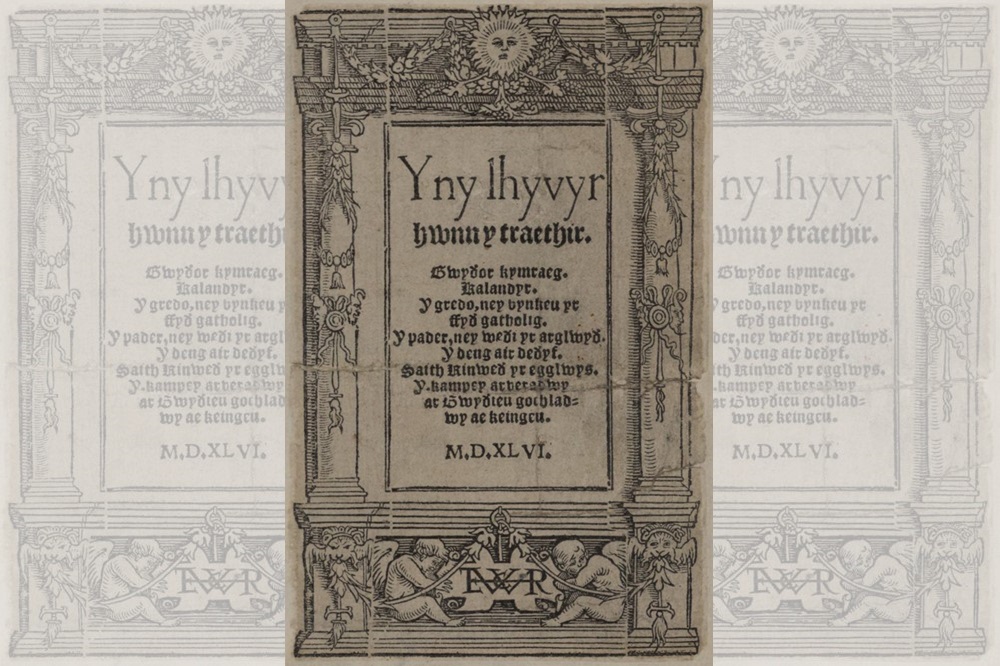

If you weren’t aware of its historical significance, you would probably find this volume to be unimpressive; it is extremely short, containing only 31 pages of material, and most of its contents are unoriginal Welsh-language reworkings of standard religious material.

These include, for example, Y deng air deðyf (‘The Ten Commandments’) and Y pader, ney weði yr arglwyð (‘The Pader or the Lord’s Prayer’).

There is also a calendar with practical advice about which activities suit which months and Gwyðor kymraeg, ‘A Welsh Alphabet’.

The publication bears no proper title, and thus it has become customary to refer to it be the first words on the first page, Yny lhyvyr hwnnor Yn y Llyfr Hwn, meaning ‘In This Book [you will find . . .]’.

It is the heading for a table of contexts rather than a book title. This short book was printed in London, as were all of the first Welsh printed books.

The press was the newest and most powerful medium for disseminating information, and it was strictly controlled by Tudor law.

It would not be legal to publish a book in Wales (or, indeed, anywhere else in England other than places stipulated by law) until the end of the seventeenth century.

Reformation

For those interested in literature more than religious history, the most interesting part of the book is an original piece written by John Prys, styled as Y Cymro yn danfon Annerch at y darlleawdr, ‘The Welshman sending a Greeting to the reader’.

The author sets his Welsh printing project soundly in the context of the king’s Protestant Reformation:

Yr awr nad oes dim hoffach gan ras yn brenin vrddasol ni No gwelet bot geirie duw a’i evengil yn kerdet yn gyffredinol ymysk ei bobyl ef, y peth y dengys ei fot ef yn dywysoc mor ddwyvawl ac y mae kadarn.

‘Now our dignified king likes nothing better than to see that god’s words and his gospel are spreading generally amongst his people, a thing which demonstrates that he is as godly a prince as he is strong.’

Following his praise of the king’s agenda, Prys adds that is thus ‘fitting’ (gwedys) that ‘some of the holy scriptures’ ([p]eth o’r yscrythur lan) are ‘put in Welsh’ (rhoi yngymraec), adding that ‘there are many Welsh people who can read Welsh, without being able to read one word of English or Latin’ (lhawer o gymry a vedair darlhein kymraeg, heb vedru darlhein vn gair saesnec na lhadin).

This, by the way, is extremely important evidence regarding monoglot Welsh literacy in the period.

New world of print

John Prys was very much aware of the fact that he was shepherding the language from the old manuscript age to the new world of print.

He notes that the things he is publishing ‘along with many other good things are written in a bunch of old Welsh manuscripts’ (gyda lhawer o betheu da erailh yn yskrivennedic mewn bagad o hen lyfreu kymraeg), adding that these sources were not ‘common amongst the people’ (yn gyffredinol ymysk y bobyl).

But now, he declares triumphantly, ‘God has placed print amongst us to increase the knowledge of his blessed words’ (Rhoes duw y prynt yn mysk ni er amylhau gwybodaeth y eireu bendigedic ef).

The task is to ensure that ‘a gift as good as this be not fruitless’ (na bai diffrwyth rhod kystal a hon).

With these words, John Prys gives us a sixteenth-century Welsh description of what made the printing press such a culture-changing invention. In the pre-print age, it was hard to make the written word [c]yffredinol, ‘common’, but print, the great rhodd or ‘gift’, could now amlhau gwybodaeth, ‘increase knowledge’.

The Welsh language and its literature was indeed entering into a new ear, and by the time Yn y Llyfr Hwn reached its first readers other Welshmen were already working to use this gift in new ways.

Darllen Pellach / Further Reading:

Neil R. Ker, ‘Sir John Prise’, yn The Library, Fifth Series, VOl. X, No. 1, March 1955.

Graham C. G. Thomas, ‘From Manuscript to Print – II. Print’, yn R. Geraint Gruffydd (gol.), A Guide to Welsh Literature1530-1700 (1997)

Geraint Gruffydd, ‘Yny lhyvyr hwnn (1546): the earliest Welsh printed book, Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies, 23.1 (Mai, 1969).

Catch up with all the previous episodes in this series here

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Something I found surprising about the book is, spelling conventions aside, how similar to modern colloquial Cymraeg it is. It’s nothing like the classical literary Welsh that I would have expected