Yr Hen Iaith part thirty: Prophecy, Poetry and Pre-Modern Proto-Nationalism: The Cywyddau Brud and the Wars of the Roses

Continuing our series of articles to accompany the podcast series Yr Hen Iaith. This is episode thirty.

Jerry Hunter

Not counting a special episode recorded in the National Eisteddfod which will be broadcast next, this is the last episode in the first series of Yr Hen Iaith.

We finish discussing literature from the Middle Ages and many themes from the series come together as we consider prophetic poems in the cywydd form connected with the ‘Wars of the Roses’.

Taliesin, the poet standing at the very beginning of the Welsh bardic tradition, Myrddin (‘Merlin’), Owain ab Urien, the battle of Camlan and many more aspects of the old literary tradition were invoked and harnessed by Welsh poets interpreting the wars between the families of Lancaster and York for the crown of England.

This bloody period came to an end in 1485 with the victory at Bosworth that made Harri Tudur King Henry VII and started the Tudor period.

However while these prophetic Welsh poets supported real participants in contemporary wars, and while Welsh soldiers fought on both side (and Welsh poets composed cywyddau in support of both sides), these bards often depicted the conflict in a deeply archaic way – as a war between the Welsh and their old enemies, the English.

Prophecy

We call these strict-metre prophetic poems cywyddau brud. As prophecy was such an essential part of the Welsh literary tradition – and, indeed, an import way in which Welsh identity was articulated – there are several Welsh words for it. Three crop up again and again: proffwydoliaeth, darogan and brud.

The history of the last of these three words is wonderfully complex. Today we used brud to mean ‘traditional Welsh prophecy’ and brut to mean ‘traditional Welsh historiographical text’ (such as Brut y Brenhinedd, ‘the Brut [or History] of the Kings’ and Brut y Tywysogion, ‘the Brut[or History] of the Princes’).

However, both share an origin in the name Brutus, the first in the long line of legendary kings, those of the Yr Hen Frytaniaid, ‘The Old Brut-ons’, held to be the heroic ancestors of the Welsh.

Cynghanedd

While the cynghanedd in poetry does at times allow us to tell whether a medieval instance has is brut or brud, medieval orthography (way of spelling) usually doesn’t differentiate between final –t and final -d.

And this ambiguity in medieval and early modern texts is extremely meaningful. Rather than seeing one as a word indexing Welsh prophecy and the other as one indexing Welsh historiography, we can argue that there was really one complex constellation of processes and concepts, which we might call brut/brud.

This complex system was a way for Welsh people to consider the past of their nation in connection with the present and the future.

Yes, I did use the word ‘nation’. Many scholars argue that nationhood is a modern concept, but there is plenty of evidence in medieval Welsh literature that Welsh poets and writers (and, presumably, their readers and audiences) conceived of a Welsh nation, although certainly not in terms of a modern nation-state.

One of the most fascinating things about these cywyddau brud is that they provide this palimpsestic or ‘double’ vision of the world in which these poets operated, the one being defined by contemporary politics and the struggle for the English crown, the other being a vision of a Welsh realm independent from England, or, perhaps, conquered by England but now fighting to win back that sovereignty.

We might define this is ‘pre-modern proto-nationalism’.

Dafydd Llwyd

Let’s look briefly at the work of Dafydd Llwyd of Mathafarn (c.1420 – c.1500), the most prolific of these poets (based on surviving manuscript evidence). One of his cywyddau brud begins with these lines:

Breuddwydion beirdd a oedwyd

Hyn sydd yn llais henwas llwyd[.]

‘The dreams of bards were delayed;

This is in the voice of a grey-haired old fellow.’

We know him as Dafydd Llwyd (‘Grey’), and he was mostly likely in his 70s when he composed this poem in support of Henry Tudur. It is possible that many such poems were composed after the victory as a way of praising the leader, rather than real prophecy composed before the event.

However, that wouldn’t change the main points about how this tradition was used to articulate and re-affirm Welsh identity.

Given the Tudor’s roots in Anglesey, the ascent of Henry VII was depicted by many poets as the Welsh finally reclaiming sovereignty which they had lost to the invaders centuries before.

That phrase, breuddwydion beirdd, ‘the dreams of bards’, resonates through the ages; these dreams were about the Welsh taking charge politically of their own fate.

It is tempting to see these cywyddau brud as political propaganda in support of a particular military campaign and/or an individual’s claim to the throne.

Medieval realpolitik

There is no denying that a late medieval realpolitik drives this work. However, it would be wrong to dismiss completely the idea that these poets and their audiences only pretended to believe in prophecy.

And before we dismiss belief in prophecy as medieval superstition, it behoves us to step back, look at our society and very recent history, and realize that even in an age fuelled by scientific discovery and vast technical knowledge, many people still believe in kinds of prophecy.

Some newspapers publish horoscopes and some people still consult Tarot cards and fortune tellers. Some religions today have a belief in prophecy ingrained in their theology (look at Revelations, the last book in the Christian New Testament, for example).

When Ronald Reagan was president of the United States, his wife Nancy consulted an astrologer and – it has been claimed – the astrologer’s advice was given to the president by his wife. If a belief in prophecy might have influenced the course of the Cold War during the late twentieth century, we should look with more understanding on people’s beliefs in the fifteenth century.

Prophecy

However, the way in which Dafydd Llwyd discusses his brut/d is not always couched as direct prophecy. It often involves studying older texts in order to learn how Welsh history unfolds.

To take as an example the first lines of another of his cywyddau:

Deall y bûm dull y byd

Cael f’addysg mewn celfyddyd

Yng ngerdd Taliesin winfaeth

Mae yn ôl am a wnaeth.

‘I understood the way of the world,

Getting my education in art

In the poetry of wine-nourished Taliesin;

There is a trace because of what he did.’

While this last line could be translated in several different ways, it is in essence a way saying that the work done by Taliesin in the past – g[w]naeth, ‘he did’ or ‘he made’ – has left a ‘track’, ‘trace’ or ‘footprint’ (ôl) which can be retraced and used in the present (with yn ôl also suggesting ‘a going/coming back’).

This is what a call Dafydd Llwyd’s ‘metapoetics of prophecy’, his conception of the ideational system driving what he does.

And it involves looping back and reinvigorating very old aspects of the Welsh poetic tradition; he uses the work of Taliesin in order to understand ‘the way of the world’ at present.

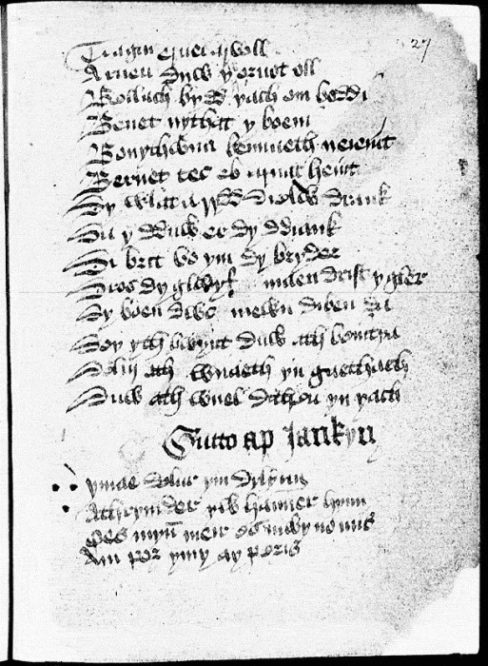

Copyright: Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru / National Library of Wales

Innovative

Like the innovations enacted by Guto’r Glyn within the confines of traditional praise poetry discussed last time, Dafydd Llwyd of Mathafarn was extremely innovative, combing the cywydd brud with other genres, including love poetry addressed to Gwerful Mechain, discussed in a previous episode this series.

He also used the ‘dialogue’ (ymddiddan) form, composing fanciful prophetic conversations between his own bardic persona and birds which rework some of the artistic mechanisms of the cywydd llatai or love-messenger poems associated with Dafydd ap Gwilym.

There is one dialogue with a seagull (gwylan), a bird used by Dafydd as the engine of prophecy which also reminds us of Dafydd’s less political gull.

Blood-thirsty

Perhaps the most blood-thirsty poem by Dafydd Llwyd is his dialogue with Y Gigfran, ‘the Raven’, a bird associated with the dead of battlefields since the earliest medieval Welsh literature.

Just like the beginning of a cywydd llatai, with the poet addressing a bird and flattering it in order to get it to take a message to a woman, this begins with a direct address to a raven.

The bird is described as proffwydes eres araith, ‘a prophetess of wonderful speech’), and as abades y gwybodau, ‘the abbess of knowledge(s)’. We are made to imagine the black bird as the head of a nunnery, a wise abbess steeped in various kinds of learning, and wearing a black habit.

Not only does the raven have the power of speech, but her language is described as ‘Brythoneg’, ‘Brythonic’, the language of the ‘Ancient Britons’, the heroic ancestors of the Welsh.

The present harks back to an ancient period, and that in the context of a continuing language and the continuation of that language’s bardic tradition, all used to emphasize the continuation of the Welsh as a people.

(It’s work noting that, according to Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru, this is the first known example of the word Brythoneg.)

Bloodshed

When the raven finally speaks, it/she prophesies, seeing battles and bloodshed. The bird is personified colourfully, imbued with a personality.

It/she looks forward to all of the death on the horizon, because the battle-field massacres will provide it/her with many a ‘feast’ or gwledd.

The bird crows gleefully Gwledd ym mhob gorsaf a gaf, ‘I will have a feast at every juncture [of the war]’.

The coming slaughter is described as Gwledd brân o gledd barwniaid, ‘a crow’s feast from the sword(s) of lords’ and it/she will enjoy ‘a feast of meat all the way to the north’, Gwledd hyd y gogledd o gig.

The word Camlan is used, invoking that bloody battle which, in legend, brought an end to the reign of Arthur. Again, this poetry is steeped in tradition, and names from earlier Welsh literature are employed in powerfully significant ways.

However, the significance of Camlan is turned on the head, providing a reverse image of that particular tradition.

If that great slaughter was said to have brought an end to the time of the archetypical Welsh hero, King Arthur, the coming bloodshed foreseen by Dafydd Llwyd’s raven will see the English defeated and the Welsh regaining sovereignty.

The bird is described as marwgoel Sais, ‘an Englishman’s death token’, leading us to view all of the dead warriors which will soon provide food for crows and ravens not as the Yorkist enemies of the Lancastrian Henry Tudor, but rather as the ancient enemies of the Welsh.

It is startingly kind of double vision; it is a palimpsest drawn in blood.

Further reading:

Gruffydd Aled Williams, ‘The Bardic Road to Bosworth: A Welsh View of Henry Tudor’, Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion (1986).

Leslie Richards (ed.), Gwaith Dafydd Llwyd o Fathafarn (1964).

Jerry Hunter, Soffestri’r Saeson: Hanesyddiaeth a Hunaniaeth yn Oes y Tuduriaid (2000).

Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru online: https://geiriadur.ac.uk/gpc/gpc.html.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Gwych!