Yr Hen Iaith part three: The Native Middle Welsh Prose Tales

Continuing our series of articles to accompany the podcast series Yr Hen Iaith. This is Episode 3.

Jerry Hunter

Let’s not call these fantastic medieval Welsh stories ‘The Mabinogion’.

That label, perhaps first used by William Owen Pughe at the end of the 18th century, was given international currency by the English translations published by Lady Charlotte Guest in the 19th century. It is interesting, strange and perhaps a little sad that the manner in which this literature was packaged for English readers in the Victorian era still influences the way in which many Welsh speakers today talk about some of the greatest works of literature produced in their language during the Middle Ages. There are eleven of these tales, and the word mabinogi only appears in four of them (‘The Four Branches of the Mabinogi’).

The plural form mabinogion only appears once in our surviving manuscript evidence, and that seems to have been a mistake. (Near the end of the ‘First Branch’, the word dyledogyon appears, meaning ‘nobles’ or ‘high-born people’, and that plural ending seems to have misled the eye and hand of the manuscript copyist a few lines letter, leading him to write mabinogyon instead of the form mabinogi which appears elsewhere).

I prefer calling them the Native Middle Welsh Prose Tales. The adjective ‘native’ is used to emphasize what makes these texts especially important: they were written originally in the Welsh language (during the period in the language’s history known as Middle Welsh, a period beginning roughly in the middle of the 12th century).

There is a great deal of medieval Welsh prose which has survived, including many other narratives, but most of this literature was translated into Middle Welsh from other languages (mostly Latin and French, but also some from English). However, rather than being translated, these eleven tales were composed in Welsh. They can thus be seen as the products of the medieval Welsh imagination – or medieval Welsh imaginations – and they are priceless examples of how the Welsh language was used 700 or 800 years ago to craft stories.

In addition to ‘the Four Branches of the Mabinogi’, this group of tales includes five Arthurian tales: ‘Culhwch and Olwen’, ‘The Dream of Rhonabwy’, ‘Geraint son of Erbin’, ‘The Story (or ‘History’) of Peredur son of Efrog’ and ‘The Lady of the Fountain’ (these last three show French influences to varying degrees, perhaps complicating the label ‘native’ in some ways). The other two – ‘The Adventure (or Cyfranc) of Lludd and Llefelys’ and the ‘Dream of Maxen Wledig’ – are stories which deal with distant Welsh-British history in imaginative ways.

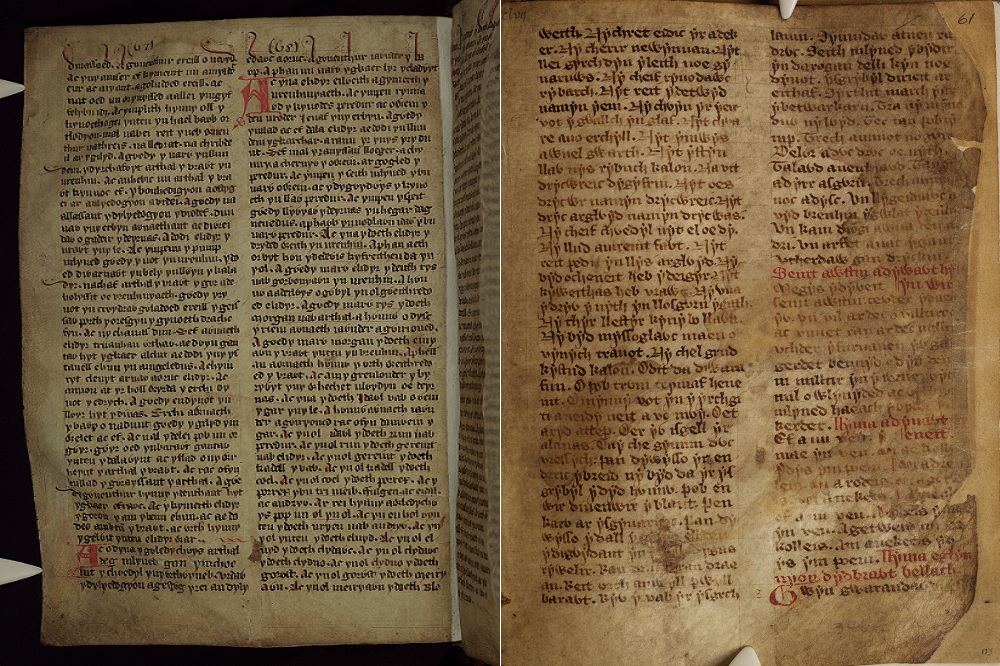

While all or parts of some are contained in a few other manuscripts, ten of these tales are preserved in The White Book of Rhydderch (c.1350) and all eleven in the Red Book of Hergest (c.1400). It’s likely that the White Book was created by Cistercian monks in the Strata Florida abbey in Ceredigion for Rhydderch ab Ieuan Llwyd.

The Red Book was created in lay (that is non-monastic) context for Hopcyn ap Tomas of Ynysforgan, a man sought out for advice by none other than Owain Glyndŵr. We’ll never know if he showed his prize manuscript to Glyndŵr, but it’s tempting to imagine the great Welsh leader taking some time to read some of the literature contained in the Red Book before returning to the pressing matters at hand.

It’s important to note that the White Book and the Red Book also contain many other kinds of Welsh literature (including prose translated from other languages). Thus, by removing these eleven ‘native’ tales and elevating them to a special status, are we doing something which violates or obscures their original literary context?

It is very likely that the men for whom these manuscripts were created, Rhydderch ab Ieuan Llwyd and Hopcyn ap Tomas, wouldn’t have thought of these tales as being more privileged, rare or important than the other texts contained in their manuscripts. And the certainly red them together with other kinds of literature.

This episode also begins a discussion – to be continued in depth in the following episodes – of the Four Branches of the Mabinogi, examining more closely the possible meanings of that troublesome word, mabinogi.

There is a tendency to read the Four Branches as medieval Welsh versions of ‘Celtic mythology’, something often driven more by a romantic desire to reclaim a distant (and irrevocably lost) pre-Christian Celtic culture than by sound reasoning.

It may be true that the name Lleu in the Fourth Branch is related to the name of a Celtic god, Lugus, recorded in early continental Celtic inscriptions. However, it’s absurd to think that medieval Welsh readers and listeners would’ve received these narratives by thinking, ‘oh yes – tales of the old gods!’

Taken as a whole, the surviving body of medieval Welsh literature suggests strongly that medieval Welsh people would’ve been proud of the fact that their people had been Christian for many centuries (and perhaps even more proud of the fact that their ancestors had been Christianized long before the ancestors of their English contemporaries).

And what about the etymology or origin of names? The English word Thursday contains the name of an old Norse god, Thor, but if you ask a group of friends ‘to meet for lunch on Thursday’, it’s very unlikely that any of them will think that you want them to gather to consume a sacred meal in the honour of the god Thor.

Describing the Four Branches of the Mabinogi as ‘tales of the old gods’ also closes off meaning and tells us very little about what these great literary creations are doing as literature. Rather than taking them as fossils of a lost and unknowable age, it is best to read them as products of – and commentaries on – the medieval Welsh culture which actually produced them.

The digital copy of White Book of Rhydderch can be seen here at Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales.

Catch up on previous parts of the story of Yr Hen Iaith here

Further Reading:

– Gwyn Jones and Thomas Jones (translators), The Mabinogion (revised edition, London, 1993)

– Patrick K. Ford, The Mabinogi and Other Medieval Welsh Tales (new edition, 2008)

– Sioned Davies (translator), The Mabinogion (Oxford: OUP, 2008)

– Diana Luft, ‘The Meaning of mabinogi’, Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies 62 (winter, 2011), 57-79.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

The name Mabinogion was well established in the 18thC and not only by Pughe but by other Welsh scholars. Charlotte Guest merely followed their tradition as she did with most of what she wrote. She was tutored by Carnhuanawc, Tegid, and others. (For the 18thC situation see Diana Luft’s various articles, and my own forthcoming on my website). I’m glad this article includes how Guest’s translations and other factors like Oxford University ‘Englishified’ the works. I very much agree the mythology aspect dominated understanding for far too long. (The tales have very little mention of anything religious at all.)… Read more »