Yr Hen Iaith part twelve: Culhwch and Olwen

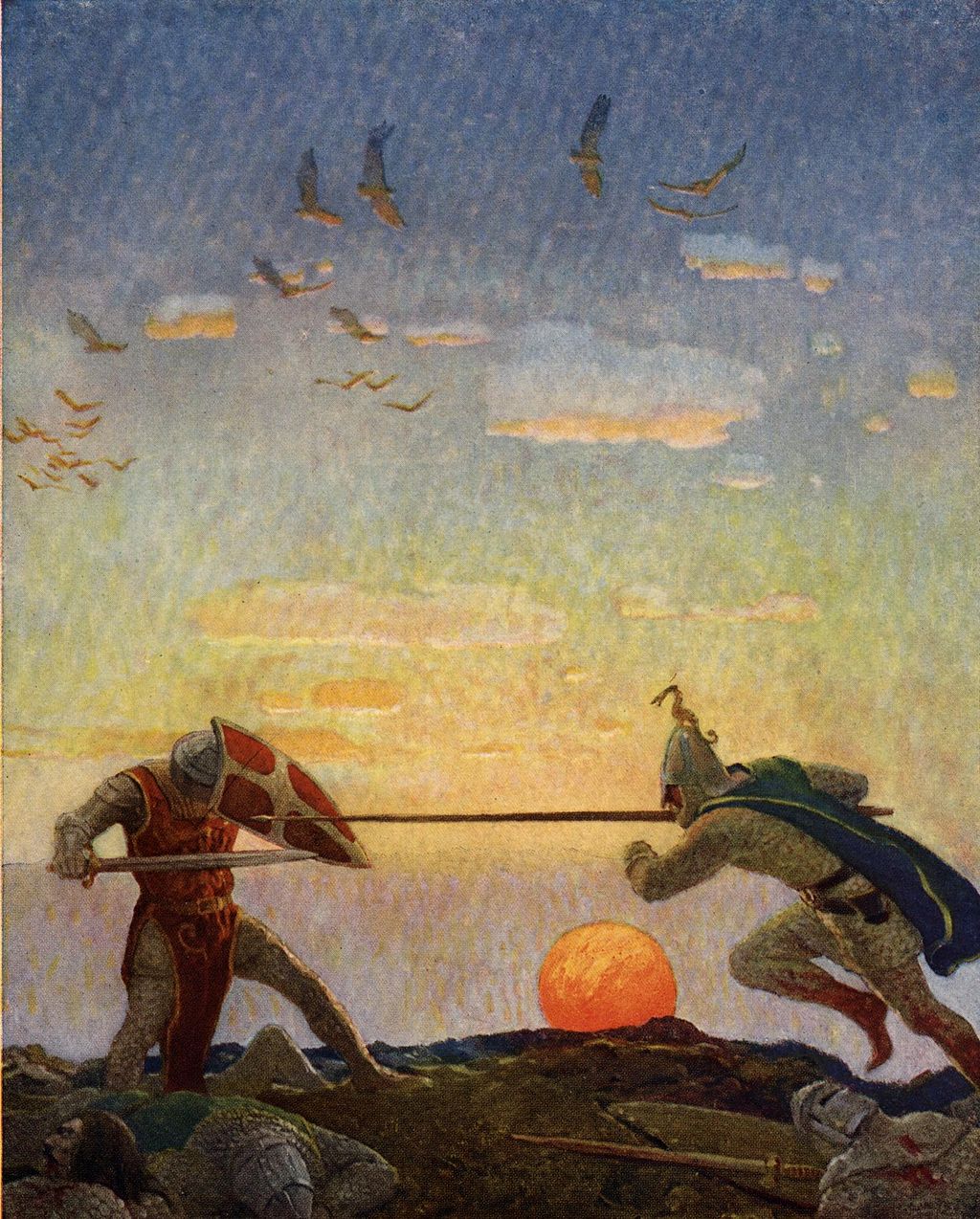

Created by Alfred Fredericks and published as an illustration to The Boy’s Mabinogion: being the earliest Welsh tales of King Arthur in the famous Red Book of Hergest, edited with an introduction by Sidney Lanier (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1881)

Continuing our series of articles to accompany the podcast series Yr Hen Iaith. This is episode twelve.

Jerry Hunter

Culhwch’s destiny has been thrust upon him by his angry stepmother. And it is a destiny designed to bring about his death: he will never be with a woman unless he is able to win Olwen, daughter of Ysbaddaden, Chief of Giants.

Following his father’s advice, he travels to seek Arthur’s help, the picture of a young hero on horseback, his battle-axe so sharp ‘that it would draw blood from the wind’ (y gwaet y ar y gwynt a dygyrchei).

We marvel at the heroic beauty, yet this Arthurian tale is not a courtly romance. The world in which we find ourselves is as brutal as it is beautiful, as savage as it is heroic.

From our modern point of view, the stepmother has every right to be angry; Culhwch’s father killed her husband and took her by force.

The medieval text, however, would have us sympathize with Culhwch. We read on in anticipation, eager to see how the legendary ruler Arthur will help him to achieve the impossible.

The tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ is the longest of the native Middle Welsh prose tales (see Episode 3). It is also important because of its vivid manifestation of native Welsh Arthurian tradition.

Scholars have dated this tale – or parts of it – to a period earlier than the manuscripts which contain it (the earliest being the White Book of Rhydderch, written around c.1350). Academic wisdom has held that ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ is the earliest surviving Arthurian tale in any vernacular (that is, a language other than Latin).

However, a very good article by Simon Rodway of Aberystwyth University’s Department of Welsh and Celtic Studies called into question some of the earlier linguistic assumptions, and it is now difficult to say whether or not parts of our Welsh tale are actually older than, say, the earliest surviving French Arthurian texts.

However, the actual date of composition is not so important; the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ remains a window on the original Welsh Arthurian world not yet influenced by literary developments in other languages and other nations.

Folktale

We can view this text as a literary experiment which does two things at the same time: it is a narrative which entertains and it is a structure which contains a huge amount of Arthurian lore.

A folktale found in different languages tells of how a hero wins the daughter of a giant or monster.

An inventive medieval author took a Welsh version of this folktale and used it as a scaffold on which to hang a great number of Arthurian characters, themes and adventures. What the triads do in that simple and concise triadic form, ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ does in narrative form.

Let’s return to the advice which Culhwch’s father gives to him: ‘Dos titheu ar Arthur y diwyn dy wallt, ac erchych hynny idaw yn gyuarws iti’ (‘Go to Arthur to cut your hair, and ask that of him as a gift to you.’)

While asking Arthur to diwyn – ‘cut’, ‘trim’ or ‘arrange’ – his hair strikes modern readers as comic and bizarre, this was surely not meant to be humorous by rather the reflection of a ritual or ceremony.

The boy’s hair is cut so that he looks like a man, and the act of hair-cutting is a personal encounter confirmation the close relationship between Arthur and Culhwch (we are also told that they are cousins, by the way).

Gatekeeper

Before gaining entrance to the hall and access to Arthur, Culhwch must first get by another traditional character, Glewlwyd Gafaelfawr, the verbose and self-important gatekeeper of Arthur’s fortress.

The young hero has arrived after those within have begun feasting, and there is a battle of words between the two (reminiscent of the dialogue between Glewlwyd and Arthur in that poem in the Black Book of Carmarthen discussed in the previous episode of the podcast).

Witty speech designed to induce laughter continues when the gatekeeper, obviously worried at this point, pops inside to tell Arthur about the striking young hero outside.

The great man’s reply is ‘Or bu ar dy gam y dyuuost y mywn, dos ar dy redec allan’, ‘if you came in walking, go out running’ and let that guy in!

When Culhwch asks for his cyfarws, his ‘gift’, Arthur is generous and replies that he will have anything he wants ‘hyt y sych gwynt, hyt y gwlych glaw, hyt yr etil haul hyt, yr ymgyffret mor, hyt yd ydiw dayar’ (‘as far as the wind dries, as far as the wind wets, as far as the sun goes, as far as the sea stretches, as far as earth is’).

Arthur’s lordly grace and beautiful, near-poetic language are then undercut by that simple but all-important word eithyr, ‘but’ or ‘except for’, and in listing the things that he will not give Culhwch the author provides a nice catalogue of Arthurian detail.

In addition to his mantel and his ship (named Prydwen in other texts, but not here), Arthur lists and names his sword, Caledfwlch, his spear, Rhongomyniad, his shield, Gwynebgwrthuchder and his knife, Carnwennan.

Mysterious

This Welsh Arthurian world is one of lush detail, and the intriguing names of these items suggests that there is a story behind each one of them.

Arthur concludes this list by naming his wife, Gwenhwyfar. (Wise, in the context of wider medieval Welsh narrative: in the First Branch of the Mabinogi, Pwyll promises a gift to a mysterious guest at feast celebrating his marriage to Rhiannon, and then has to deal with a huge problem when the man requests Rhiannon!)

The narrative has built up to this dramatic juncture, and Culhwch finally asks Arthur to get him Olwen. In order to add extra force to the request, Culhwch ‘invokes’ (‘asswynaw’) her in the names of Arthur’s ‘warriors’ (‘[m]ilwyr’).

In many societies around the world and through history, a speech act in a formal setting has legal force and calling upon witnesses present can be an important part of that legal (or magical) contract.

This still happens today in many wedding ceremonies (‘I call on those present to testify that I take you as my lawfully wedded wife/husband,’ etc.).

Heroes

We imagine Culhwch looking around Arthur’s packed hall, recognizing all of the faces, and proceeding to name the heroes gathered there in the court. And he names more than 250 of them, often grouped in triads and often including a short description of a hero’s attributes.

This list is a tour de force display of our anonymous author’s mastery of Arthurian lore – mastery in the sense that many of those named are or were traditional characters surely featuring in other stories now lost to us, but also in the sense that this writer ‘masters’ that tradition by having fun with it, at times inventing his own embellishments.

He first names Cai and Bedwyr, appearing in other texts as the foremost of Arthur’s heroes. The description of some characters is humorous, and the tone that humour is consistently fantastical, usually mind-bendingly extreme, and often grotesque.

For example, Hir Erwm and Hir Atrwm (both described as hir, ‘long’ or ‘tall’) are unparalleled gluttons:

y dyd y delhynt y west, trychantref a achubeint yn eu kyuereit, gwest hyt nawn a diotta hyt nos. Pan elhynt y gyscu, penn y pryuet a yssynt rac newyn mal pei nat yssynt uwyt eiroet. Pan elhynt y west nyd edewynt wy na thew na theneu, na thwym nac oer, na sur na chroyw, nac ir na hallt.

‘the day they came to feast, they would take tree cantrefs for their needs, feasting until noon and drinking until night. When they went to sleep, they would eat the heads of insects to stave off hunger as if they hadn’t ever eaten food. When they went to a feast they would leave neither fat nor thin, neither warm nor cold, neither sour nor fresh, neither fresh nor salted [without consuming all of it].’

There is Gwefyl son of Gwastad (‘Lip son of Level’), who, when, lets his bottom lip hang down to his navel and throws his top one over his head like a hood.

And there is Uchdryd Faryf Draws (‘Cross-Beard’) who can throw his large, bristling red beard over the fifty rafters in Arthur’s hall.

Source The Boy’s King Arthur: Sir Thomas Malory’s History of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table, Edited for Boys by Sidney Lanier (New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1922).

Conflict

One intriguing section of the list quotes a triad, naming the three men who escaped from the Battle of Camlan – the apocalyptical conflict which brought an end to Arthur’s reign.

Rather than a slip on the part of the author (‘how can this be’, a reader might protest, ‘Arthur is alive and well and at the height of his power here in this tale?!’), I see this is something profound, bringing reference to the end of the vast, detailed Arthurian story into the middle of that story, thus making this list of Arthurian characters a truly comprehensive role-call not just of names but also of narrative content. (This is interesting and complicated; we might have to devote an entire episode to literature relating to Camlan in the future!).

In the previous episode, I suggested that we can see Arthur as a great planet with gravity so powerful that it attracts lesser bodies to orbit it as satellites.

This long, colourful list of Arthur’s ‘milwyr’ or ‘warriors’ is a fantastic display of Planet Arthur at work, the centre of a multitude of satellites, many pulled from other Welsh traditions – Terynon Twryf Bliant and Manawydan son of Llŷr from the Four Branches of the Mabinogi, and the legendary poet Taliesin, for example – and some drawn across linguistic boundaries from the traditions of other peoples.

There are several names derived from Irish tradition, for example, including Cnychwr fab Nes, a Middle Welsh version of Conchobar mac Nessa, the king in the Ulster cycle of tales.

Imaginative

And this allows us to focus on an important point: ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ is a window onto the ‘original’ Welsh Arthurian world, one not yet changed by imported Arthuriana from the literatures of other languages.

But that Welsh imaginative realm was not insular; rather than been inward-looking, the anonymous author of this Welsh Arthurian tale included elements familiar to him from other traditions.

This vision of Arthur is uniquely Welsh, but that includes an assumption that he was such a great figure that he would attract followers from many lands.

Unlike other Welsh Arthurian tales which present a vision of Arthur, his court and his world influenced profoundly by French Arthurian romance, the fundamental nature of Arthur, his court and his world in ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ is not effected by that kind of structural narrative influence.

Roll call

So, Culhwch names more than 250 characters present in Arthur’s hall, often describing what makes each one special.

When he finally finishes this amazing roll-call, we imagine the young man standing there before Arthur, out of breath, expectant, waiting for Arthur’s response to his request that he obtain Olwen for him.

Arthur’s answer is a masterpiece of comic contrast, given the trouble to which Culhwch has gone to elicit this reply: ‘ny rygiglef i eirmoet y wrth y uorwyn a dywedy di’ (‘I have never heard of the maiden of whom you speak’).

This has to be one of the great anticlimaxes of world literature, and it’s fashioned by this author in order to play a joke on the reader and create humour which is singly unexpected and extremely absurd.

But Arthur agrees to send out messangers to search for Olwen, and we’ll discuss the results of that search next week.

Further Reading:

Gwyn Jones and Thomas Jones (translators), The Mabinogion (revised edition, London, 1993)

Sioned Davies (translator), The Mabinogion (Oxford: OUP, 2008)

Rachel Bromwich a D. Simon Evans (goln.), Culhwch ac Olwen (Caerdydd: Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru, 2012).

Rachel Bromwich, A. O. H. Jarman a Brynley F. Robers (goln.), The Arthur of the Welsh: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval Welsh Literature (Caerdydd, 1991)

Simon Rodway, ‘the date and authorship of Culhwch ac Olwen: a reassessment’, Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies 49 (1005).

You can catch up with the previous episodes here

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

A fuasai Jerry Hunter yn medru cadarhau mai Cymreigio enw Conochbar fab Ness i Cnychwr ydi yr enghraifft gynta o joyddc fudur yn Gymraeg?. Arthur Owen,Caerdydd

‘joyddc’ joc o ni yn ei feddwl.