Yr Hen Iaith part twenty four: Drinking in Niwbwrch: Dafydd ap Gwilym

Continuing our series of articles to accompany the podcast series Yr Hen Iaith. This is episode twenty four.

Jerry Hunter

Dafydd ap Gwilym was the right poet in the right place at the right time. The place was of course Wales, and while this prolific poet seems to have travelled from Glamorgan to Anglesey (and composed poetry to and about people and places in these various places), Llanbadarn Fawr near Aberystwyth seems to have been his home.

While the exact years of his life are difficult to pin down, he seems to have been born around 1315 and to have died around 1350 (perhaps during the Black Death).

He was born roughly a generation after the native Welsh princes were extinguished in 1282 and he grew up in a Wales which had been changing politically and culturally and which continued to do so during his lifetime.

Original talent

And, he was the right poet in that time and place. The surviving poetry connected with his name is the product of an arrestingly original talent and it is characterised by a certain artistic adventurousness, exploring intertwined themes of love and nature in new and exciting ways.

This was not invented out of thin air. In an earlier episode of our podcast, we discussed the 12th-century poet Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd, who composed love poetry which also extols the beauties of his native land.

And it is very likely that there were traditions maintained by lower classes of poets which were not recorded previously and only transmitted orally.

Influences

Literary influences had been coming into Wales for some time by Dafydd’s day, and it seems that French love poetry was a particular influence on him.

Bringing all of these strands together, we can summarize and suggest that Dafydd ap Gwilym was a poet able to absorb and adapt a range of different sources and influences – whether ‘foreign’ in origin or ‘native’ Welsh folk traditions not previously considered the proper fare for a respectable poet – and he had the talent and vision to turn all of these influences into some of the most original and memorable literature produced in any European language during the medieval period.

Singer

Dafydd’s life and career coincides with the start of a long period of Welsh literary history, that of the cywyddwyror poets composing in the cywydd metre.

That word is actually found in a very early Welsh text, one of the ninth-century englynion verses written as marginalia or literary graffiti in a Latin manuscript.

That was the stage of the language linguists term Old Welsh, and the Old Welsh word couid (cywydd) sems to have meant ‘a song’ of some kind.

A Brut – a historiographical prose text – found in the Red Book of Hergest (c. 1400) uses kywyd wr (cywydd-wr) to mean ‘a singer’.

It is not until the century following Dafydd ap Gwilym’s life that we find a poet, Guto’r Glyn, using the term cywyddwr to refer to a contemporary poet who, like Guto himself – and like many other poets before and after him – used the cywyddmetre.

And that is how we use the term cywyddwr (plural cywyddwyr) today, to refer to the large number of poets who used this form from the second quarter of the 14th century onwards (up until at least the end of the 17th century, although cywyddau have been composed during every century since then, and, indeed, there are many excellent cywyddwyr and cywyddwragedd writing today!)

Sound

Bardic grammars were being written, copied and studied during the first centuries of the cywyddwyr, and the cywydd – or, to give it its full name, cywydd deuair hirion (‘a long-line couplet’) – was codified as a specific strict metre (couplets with a stressed final syllable in one line rhyming with an unstressed final syllable in the couplet’s other line).

Being a ‘strict’ metre, cynghanedd internal line ornamentation is expected in each line. (It’s important to stress how wonderfully complex the Welsh strict metres are; students of English poetry might think that the sonnet is a challenging form, but a sonnet is a ‘free metre’ in the Welsh context, as it doesn’t have cynghanedd.)

While a strict metre with complex rules governing its composition, the cywydd is also a flexible medium in the hands of an able poet.

As the couplet is the essential building block, a poem in this metre can in theory be of any length, ranging from one couplet to many hundreds of them (and 19th-century poets often composed staggeringly long cywyddau!).

Dafydd ap Gwilym and other talented cywyddwyr often run complete grammatical sentences adeptly across many couplets, while the sound of the poem simultaneously focuses a listener’s ears on the couplets as they run by.

It is a medium allowing the blending of intense musicality as well as overlapping and complicated meaning(s).

Performed poems

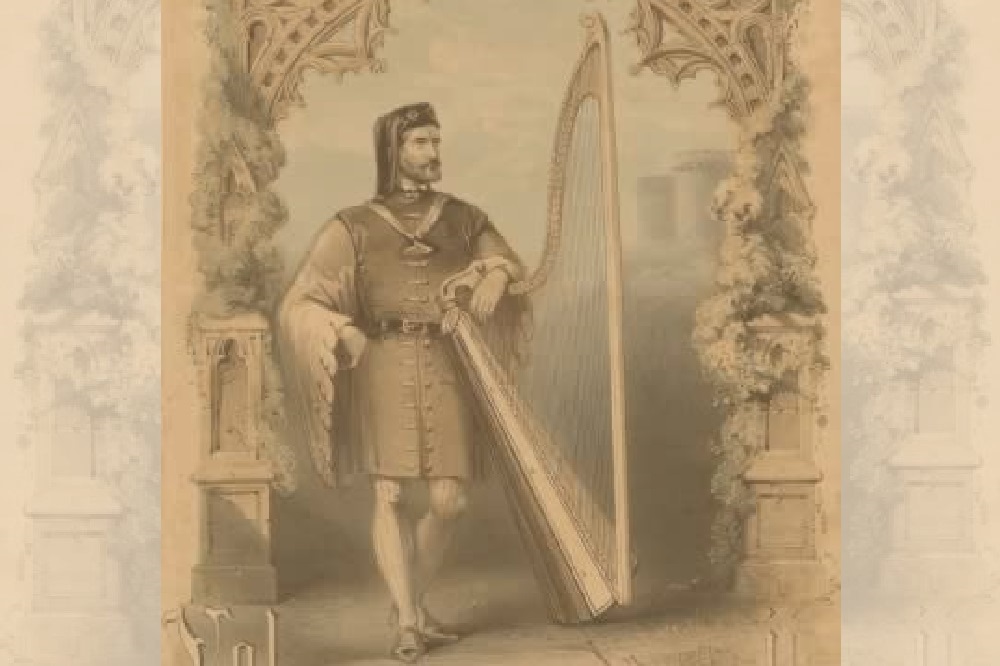

And sound is key. These poems were meant to be performed, and it is almost certain that Dafydd sang his own cywyddau, accompanying himself on the harp.

In a very real sense, cywyddwyr of Dafydd’s day were also ‘singers’ in the sense implied by the earliest recorded instances of that Welsh word.

While Dafydd was certainly an innovator in many ways, he also had one artistic foot planted soundly in ancient Welsh tradition. People today tend to associate him with his love and nature poetry, but he also used treated a range of other topics.

Like the Poets of the Princes before him, he sung praise poetry to patrons, sometimes using that older and more elevated strict-metre form, the awdl, as well as the newer cywydd. And also composed some religious poetry – work which is serious, meditative and profound.

We can also see cross-fertilization, as Dafydd used elements drawn from ancient Welsh bardic practice to inflect his lighter and more adventurous ‘newfangled’ poetry and brought his original take on things to temper work composed in more traditional genres.

Praise

In addition to composing praise to living people and to sacred subjects, he composed a cywydd praising a place, Niwbwrch (Newbourough).

Later cywyddwyr would also praise specific places, but this is the earliest one which survives. Once again, because he innovated and introduced new ways of doing things or because other work by other poets has not survived, Dafydd seems to stand at the start of a new chapter in Welsh literary history.

The first word in the first line of this vibrant poem, a Middle Welsh greeting, is used to begin more than one of his cywyddau:

Hawddamawr, mireinwawr, maith,

Dref Niwbwrch, drefn iawn obaith,

A’i glwysteg deml a’i glastyr,

A’i gwerin a’i gwŷr,

A’i chwrf a’i medd a’i chariad,

A’i dynion rhwydd a’u dan’n rhad.

‘Great greetings to the town of Newborough,

[beautiful like a] splendid dawn, the proper home of hope,

And its fair and beautiful church and its blue [or green or grey] towers,

And its wine and its [common] folk and its men [of status],

And its beer and its mead and its love,

And its generous people giving their wealth.’

Musical

Tropes familiar from centuries of poetry praising kinds and princes are used to praise the town. As we are caught up in the musical flow of these initial lines, we are given an immediate sense that the entire town of Niwbwrch is this poet’s patron.

That ancient word clod, ‘praise’ – connected etymologically to the word clywed, ‘to hear’, because praise sung by a poet was something heard and made real in the hearing – is also employed in a wonderful phrase, as Dafydd calls the town ‘pentwr y glod’, ‘the mass of praise.’

Throughout this poem he actively heaps praise upon the town, actively making it the ‘mass’ on which praise is heaped.

Drink

Dafydd stresses that Niwbwrch is an especially welcoming place for poets, declaring it to be ‘lle rhwydd beirdd’, ‘the generous place of [or ‘for’] bards’ and lle diofer i glera, ‘a place worth visiting when travelling as a poet’. Just as poets enjoyed wine, mead and beer in the halls of their patrons, so poets drink freely in Niwbwrch, as stressed by the opening lines quoted above. This is emphasized several times by means of some wonderfully creative images.

The town is ‘mynwent medd Môn’, ‘Anglesey’s graveyard of mead’, suggesting that Dafydd and others ‘burry’ great quantities of the drink in their stomachs.

He also describes Niwbwrch as both his ‘castle and his mead-cellar’ (‘castell a meddgell i mi’), suggesting in succinct phrasing that he receives both shelter and enjoyment there.

New borough

While Niwbwrch was a more recent name, borrowed from the English Newborough, Dafydd also refers to the area by its old Welsh name: ‘cornel ddiddos yw Rhosyr’ (‘Rhosyr is a cosy corner’).

The new borough was the result of what we’d call ethnic cleansing today; after the conquest, Edward I had the inhabitants of Llan-faes removed in order to build the castle and town of Beaumaris. The native Welsh residents were relocated and forced to build a new town in another part of the island.

However, they were relocating to place laden with historical significance, for Rhosyr had been the site of the court of the kings of Gwynedd and princes of Wales. Indeed, after introducing the name Rhosyr Dafydd describes it with a meaning-laden line:

‘Llwybrau henw lle brenhinawl’

‘Distinguished streets of a royal place’.

If Beaumaris was the ‘royal place’ of the Anglo-Norman king, Dafydd reminds us that Niwbwrch is also Rhosyr, the royal place of Welsh rulers.

Full of historical resonance and intensely meaningful in terms of Welsh identity, this is also a way of saying that he now enjoys what we might call a royal welcome in the Welsh town.

Darllen pellach / further reading:

Thomas Parry, Gwaith Dafydd ap Gwilym

Huw Meirion Edwards, Dafydd ap Gwilym: Influences and Analogues

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.